A small brass plaque twinkles in the pavement between two pots of yellow pansies: “Here lived Bart Witteman, born 1896, in the resistance,” it reads. It then lists the date that this policeman in the Dutch city of Haarlem, who sheltered Jewish people, was arrested, deported and murdered by the Nazis.

Eighty years after his murder, on 11 March, his grandson Ton Witteman laid this “stumbling stone” in front of the quiet terrace where his grandfather lived. With the blessing of the present homeowners, the pavement became part of an artistic project by the German artist Gunter Demnig—but a controversial one.

With the agreement of the current residents, the plaque was laid outside the house where Bart Witteman sheltered two Jewish people Courtesy Ton Witteman

The brass plates, a little under 10cm square, are known as stolpersteine in German and struikelstenen in Dutch, and represent more than 100,000 symbolic reminders of the victims of National Socialism across Europe.

In Haarlem, where in 1941 the Nazis installed a sympathetic mayor, the municipality had a plan to lay stones for the 733 murdered Jewish, Sinti and Roma people. But when Ton Witteman asked to mark the house where his policeman grandfather had lived—with four children and two Jewish people undercover—he got short shrift at the town council. So, he requested a hand-stamped stumbling stone from the Stolpersteine project, provided evidence of his grandfather’s heroism and laid the piece himself.

“Gunter Demnig developed these stumbling stones to lay before the houses where someone last lived in freedom, so that you simply come across them in the street,” he tells The Art Newspaper. “My grandfather is remembered as a policeman in the police station in Haarlem, where there is a plaque of seven names of fallen policemen including his. But this is a place for us to go to. He lived here; this is where he was taken away. And in the Second World War, there weren’t so very many heroes.”

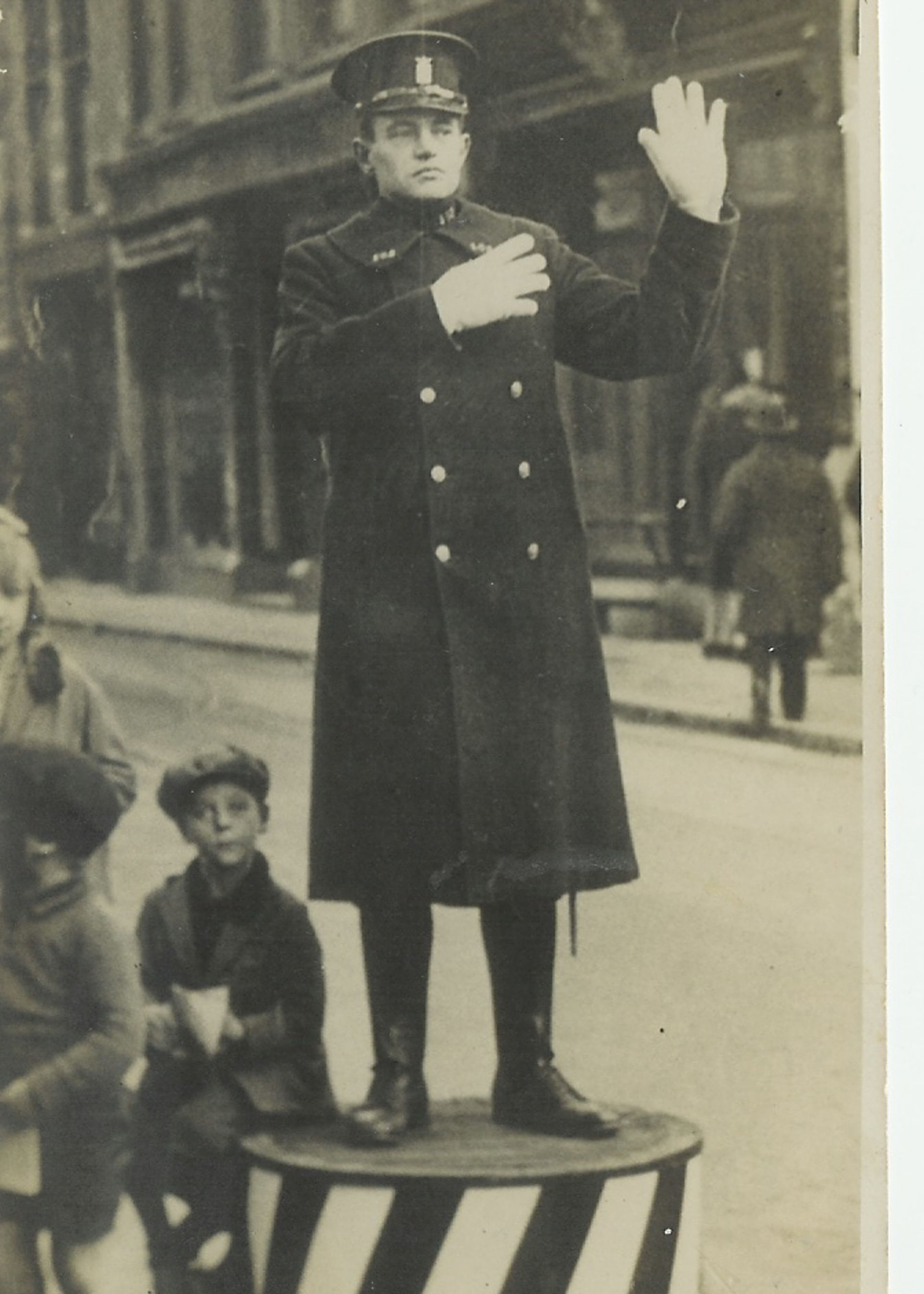

Bart Witteman directing traffic in Harlem. After the discovery that he was sheltering Jewish people, he was arrested, deported and murdered by the Nazis Courtesy Ton Witteman

Other cities around the Netherlands, such as The Hague, Utrecht and Maastricht, use the Stolpersteine project to recognise political victims of the Nazis, such as communists who were gassed at the Bernburg psychiatric clinic in Germany in 1942. Two campaigners, Jan Boxem and Steven Brandsma, have been trying to lay stones for this forgotten group, including in Haarlem.

Alexander Stukenberg, the executive director of the Stolpersteine foundation, says the organisation responds to requests to create stones to be laid all over Europe, if the evidence shows people were indeed victims. “Gunter Demnig says that stolpersteine are for all victims of the Nazis, and the dream could even be that a victim from England or North Africa who had to do forced labour in a factory in Germany also gets one,” he tells The Art Newspaper.

Haarlem's mayor, Jos Wienen, said in a council meeting that it would not offer struikelstenen for other victims of the Nazis—but it would not remove Witteman’s illicit stone, either. And, thanks to Witteman’s action, the city has now voted to create its own memorial pavestone, inspired by Demnig, for other victims of the Nazis who were not part of the Jewish, Roma or Sinti communities.

“It is extraordinary how much this war and the horrors it brought with it are still very much alive 80 years later, and that there is such a need to reflect on them,” he said. “There’s a question about how you deal with these sorts of memories, remembrance stones, stumbling stones…but what unites is that we all want to offer them a place and a form.”

Gerard van Klooster, Ton Witteman’s cousin and a Haarlem resident, has no regrets about the city's only stolpersteine for a man who resisted the Nazis. “If something like this is there, maybe a lamp goes on and people think also about Ukraine,” he says. “It brings it close to home.”