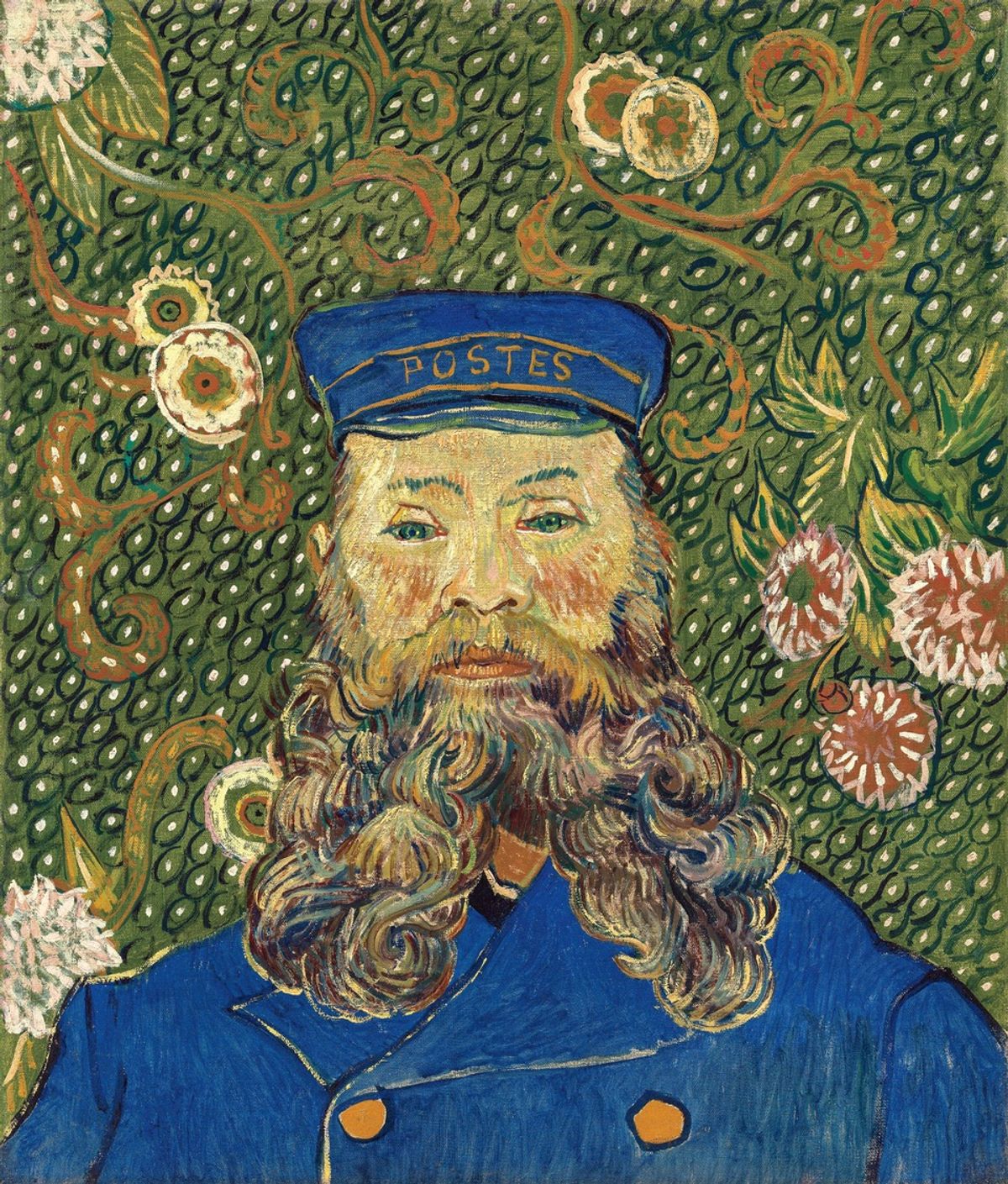

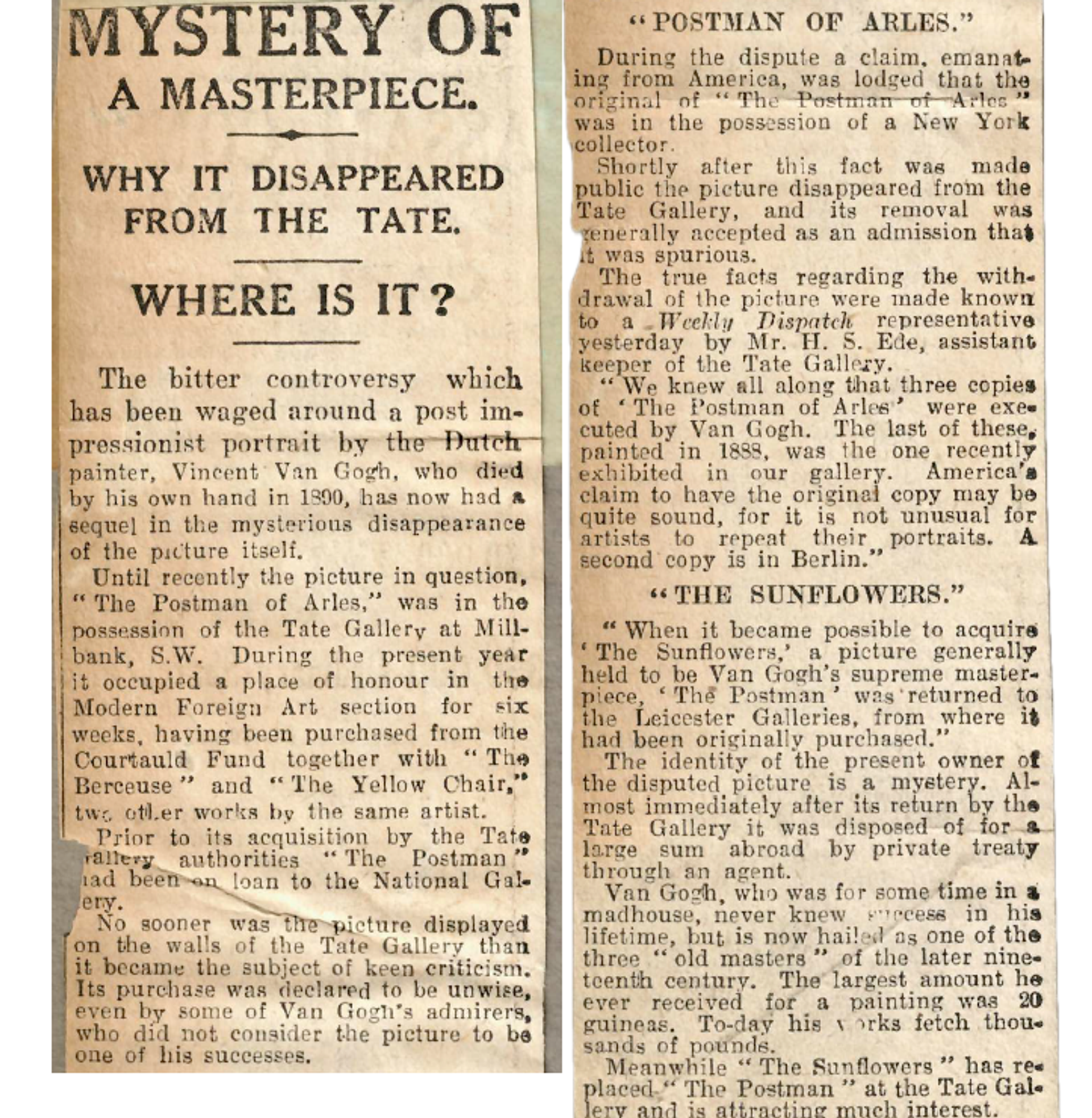

When Van Gogh’s painting, the “Postman of Arles”, was removed from the Tate Gallery just over a century ago, London’s Weekly Dispatch was left baffled by the mysterious loss. On 25 May 1924 the newspaper reported that the portrait of Joseph Roulin had been hanging in “a place of honour in the Modern Foreign Art section”—but it had then disappeared.

Article in London's Weekly Dispatch, 25 May 1924

National Gallery, London (photograph)

The Weekly Dispatch noted that the picture had been subjected to “keen criticism” when it was hung at the Tate Gallery in Millbank in December 1923: even some of Van Gogh’s admirers “did not consider the picture to be one of his successes”. Others believed (quite wrongly) that it might be a fake.

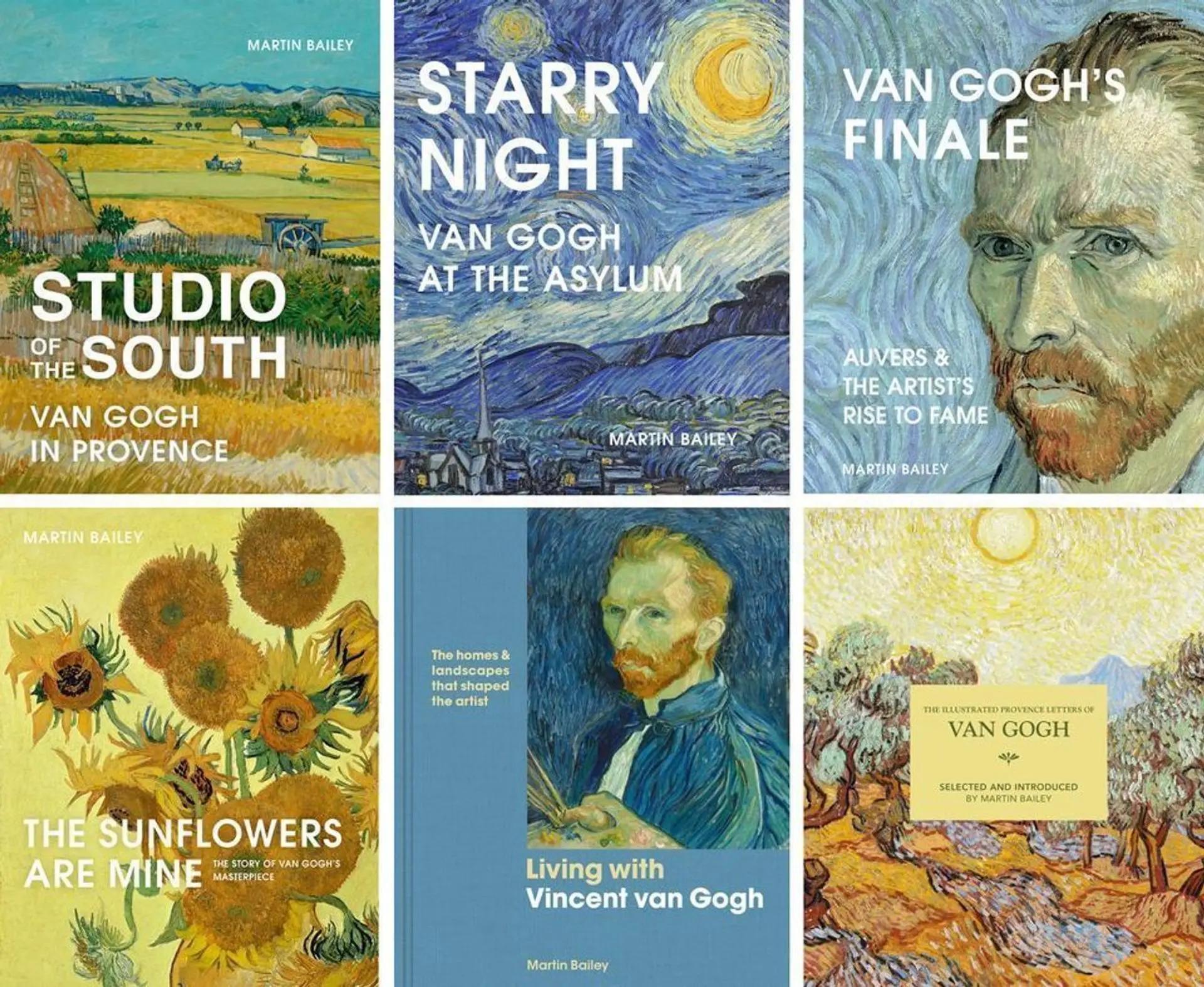

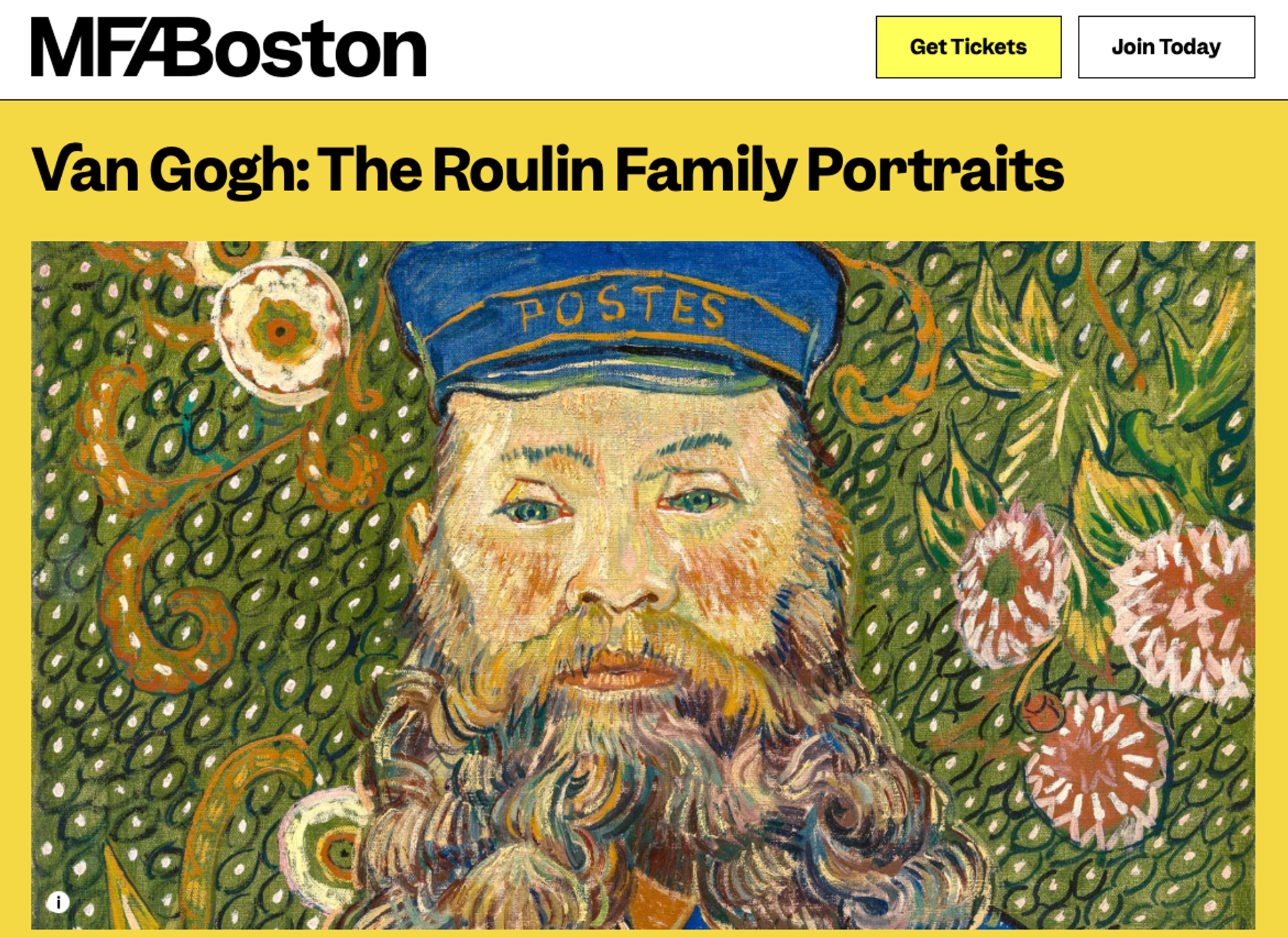

Portrait of Joseph Roulin ended up being acquired by New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1989. It is now the lead publicity image for the exhibition opening at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, Van Gogh: The Roulin Family Portraits (30 March-7 September). The MoMA painting will then travel to the show’s presentation at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam (3 October-11 January 2026).

In 1924 there were rumours that Portrait of Joseph Roulin was “spurious” and the Weekly Dispatch suggested that the original was in a New York collection. This was based on a misunderstanding, since Van Gogh had painted five head-and-shoulders portraits of the postman, who was the artist's best friend when he was staying at the Yellow House in Arles. All five versions are somewhat different.

“There is no mystery”

However, it is true that by this time one of the portraits was indeed in the US, having been the first Van Gogh to be bought by an American. In 1912 it had been acquired by the distinguished collector Albert Barnes, who lived in Philadelphia, not New York.

Following the Weekly Dispatch’s speculative article, the fate of the painting was explained in a letter to the editor published a week later. In this letter, the directors of the Leicester Galleries, which was handling the UK sale of Van Gogh works for Vincent’s sister-in-law Jo Bonger, explained that the postman’s portrait had originally been bought by the Courtauld Fund trustees for the Tate. But when Bonger reluctantly agreed to sell the more important Sunflowers (August 1888), the portrait of the postman was returned to the Leicester Galleries. “There is no mystery”, the directors' letter concluded.

Van Gogh’s Portrait of Joseph Roulin was traded in for the Sunflowers (August 1888)

© Museum of Modern Art, New York (licensed by Scala/Art Resource, New York) and National Gallery, London

The postman's beard was “too funny”

Jim Ede, then the Tate’s assistant keeper, recalled many years later that the Roulin portrait had been returned to the Leicester Galleries because the Courtauld trustees felt that “his beard was too funny”. Charles Aitken, the Tate director, had put it more diplomatically in a letter to Bonger on 19 January 1924. He wrote: “Mr Courtauld feels that ‘The Postman’, fine as the face is, is not, taking it as a whole, quite adequate to represent Vincent van Gogh.”

However, Van Gogh does appear to have successfully caught Roulin’s striking appearance. In a letter to his brother Theo, Vincent described the postman as having “a big, bearded face, very Socratic”—Socrates was renowned for his shaggy beard. A 1902 photograph also shows his unusually bushy beard.

Photograph of Joseph Roulin (1902)

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

After the Tate returned Portrait of Joseph Roulin, the Leicester Galleries sold it on almost immediately. A month later it was bought by the Lucerne-based Thannhauser gallery. So it was in Switzerland when the Weekly Dispatch ran its article.

For the next two years Thannhauser hawked around the painting at considerably higher prices. It was offered to eight museums—including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the Detroit Institute of Arts—all of which declined it.

Acquired by MoMA

Eventually, in March 1926, it was bought by the Zurich collector Bernhard Mayer. His heirs sold the portrait in 1989 through two Swiss dealers, Thomas Ammann and Ernst Beyeler, and it was then acquired by MoMA.

In a complicated arrangement, MoMA deaccessioned seven paintings in return for the Van Gogh. The dealers received four MoMA works by Renoir, Monet, Kandinsky and Picasso. Three by Mondrian, de Chirico and Picasso were auctioned to raise the remainder of the price. The value of the Roulin acquisition has never been disclosed, but it was most likely tens of millions of dollars—quite a rise from the £870 paid by the Courtauld Fund trustees on behalf of the Tate.

In 1989 the Portrait of Joseph Roulin was traded in a somewhat similar way to that which occurred with the Courtauld Fund trustees' purchase in 1924. On the first occasion, the painting had been regarded as somewhat inferior, so a cash sum needed to be paid on top to acquire a better Van Gogh. On the more recent occasion, MoMA traded in seven works by Modern masters to acquire a single Van Gogh.

Times change, and MoMA’s postman is now regarded as one of Van Gogh’s finest portraits. Now it is the star loan of the Boston exhibition.

Publicity image for Van Gogh: The Roulin Family Portraits at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

As for the Sunflowers, it is now displayed at the National Gallery. In 1924 the Tate had been run under the National Gallery’s authority and the Van Gogh masterpiece was transferred to Trafalgar Square in 1961.

Other Van Gogh news:

Sunday 30 March will be the anniversary of Van Gogh’s birth in 1853. For his 37th birthday—also his final birthday, which he spent in the asylum—his elderly mother Anna sewed him “a tobacco pouch” and sent “a tin of chocolate”. She wrote with concern to her daughter Wil: “Poor fellow, may he see better days.”