Soil, dirt, earth—whatever you want to call it, most of us don’t give much thought to the stuff that lies underfoot. Which is a big mistake, according to Soil: The World at Our Feet, an exhibition at Somerset House, London, which offers a comprehensive celebration of this precious substance. For not only is soil the stuff of life, upon which we all depend for our nourishment and our very survival, but it is also teeming with mysterious marvels and restorative powers.

Far from being dark and dull, soil is the single most biodiverse habitat on our planet and contains half of all species. And, while many of these myriad minibeasts and their environment-enhancing activities cannot be seen by the naked eye, what amazing creatures they are.

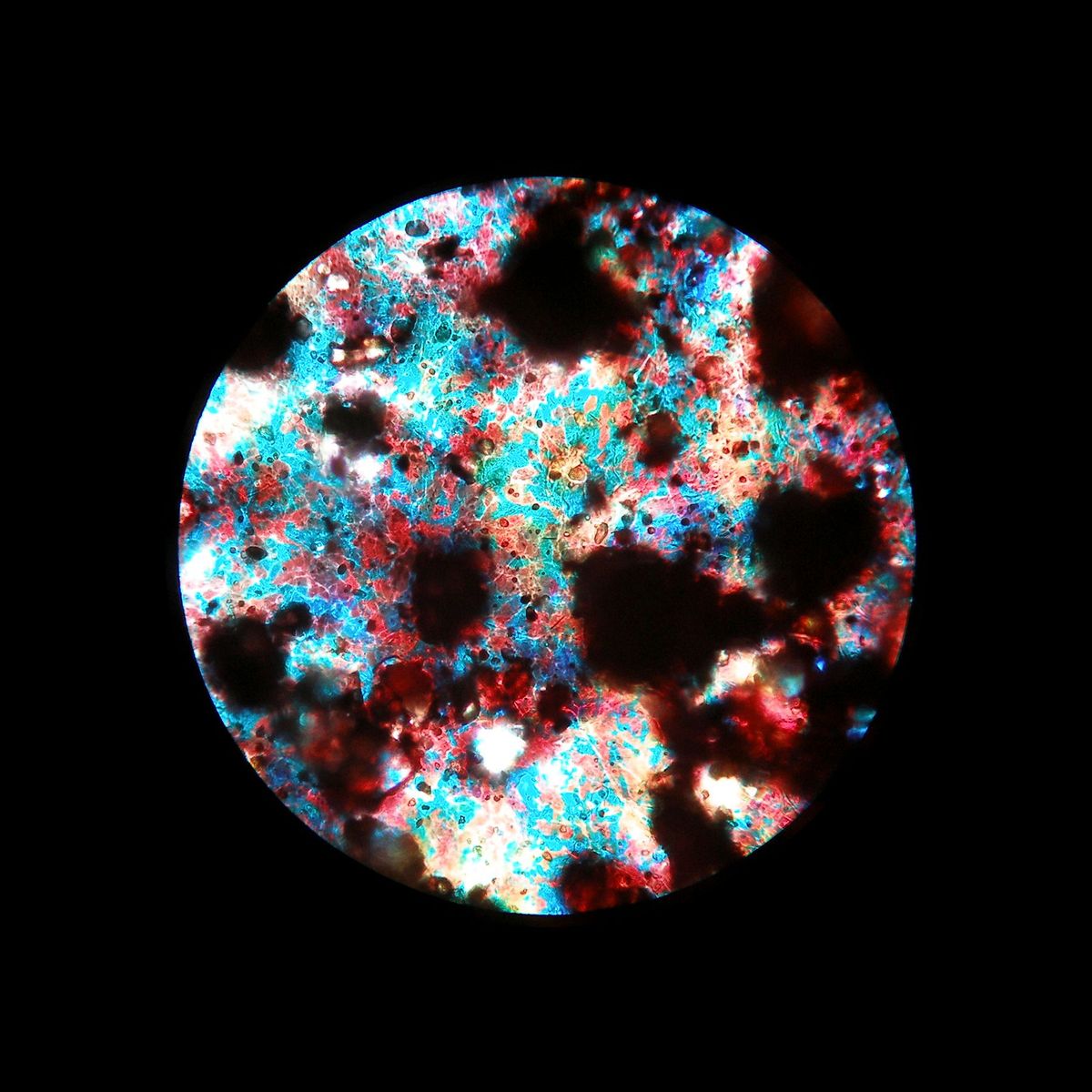

Now thanks to this literally groundbreaking show, we can view these microscopic powerhouses in all their glory. In the brown-painted first galleries, a series of multicoloured planet-like discs bear vivid evidence of the activity of micro-organisms, soil placed by the artist Daro Montag interacting with moistened film. Jo Pearl, meanwhile, uses the clay of the earth to model a multitude of strange, suspended ceramic forms, some with tentacles, others forming spirals, stars or clustered spheres, all of which replicate the extraordinary and various miniscule creatures that exist in a piece of healthy soil.

Still from one of Wim Van Egmond time-lapse Soil in Action films, depicting a mating and egg laying earthworm (still)

© Wim van Egmond

“I always find it a bit tragic that the whole machine is kept running by micro-organisms in the soil but nobody sees or notices them,” says Wim Van Egmond, whose time-lapse Soil in Action films, created in collaboration with the soil ecologist Gerlinde De Deyn, make these earthly lifeforces visible to stunning effect. Seeds germinate, roots sprout, networks of mycelium spread, worms burrow and cycles of rotting and regeneration unfold, all magnified, speeded up and projected on an immersive scale.

These hidden processes become even more engaging when accompanied by Michael Prime’s soundscape, which broadcasts the sound of electrical currents exuded by a peyote cactus as it extracts water and nutrients from the ground and exchanges them with buried fungi.

Fungi are among the unsung heroes of soil, permeating, nourishing and linking up the underground world. One of the stars of the Somerset House show is the red and white spotted Fly Agaric toadstool, which lives up to its magical fairytale image in a trippily spectacular film made by the artist collective Marshmallow Laser Feast. Fly Agaric 1: Poetics of Soil sees the fungal pinup twirl and swirl, sending out glittering clouds of spores into the atmosphere while below the surface its roots simultaneously merge with and break down organic matter as they extend deep in glittering skeins.

An installation view of Fly Agaric by Marshmallow Laser Feast

Photo: David Parry, PA Media Assignments

The role of soil as the great interconnector, acting upon and being acted upon by all life forms is also strikingly accentuated in France Bourely’s insect “portraits” of underestimated earthly movers and shakers such as the ant, dung beetle and bee. Captured in minute monochrome detail under an electron microscope, these familiar critters are transformed into imposing alien presences, with Bourely declaring the purpose of her scrutiny being “to discover new personalities and to reveal their fine technologies, which show me how every part of life is connected and that nothing is insignificant or useless”.

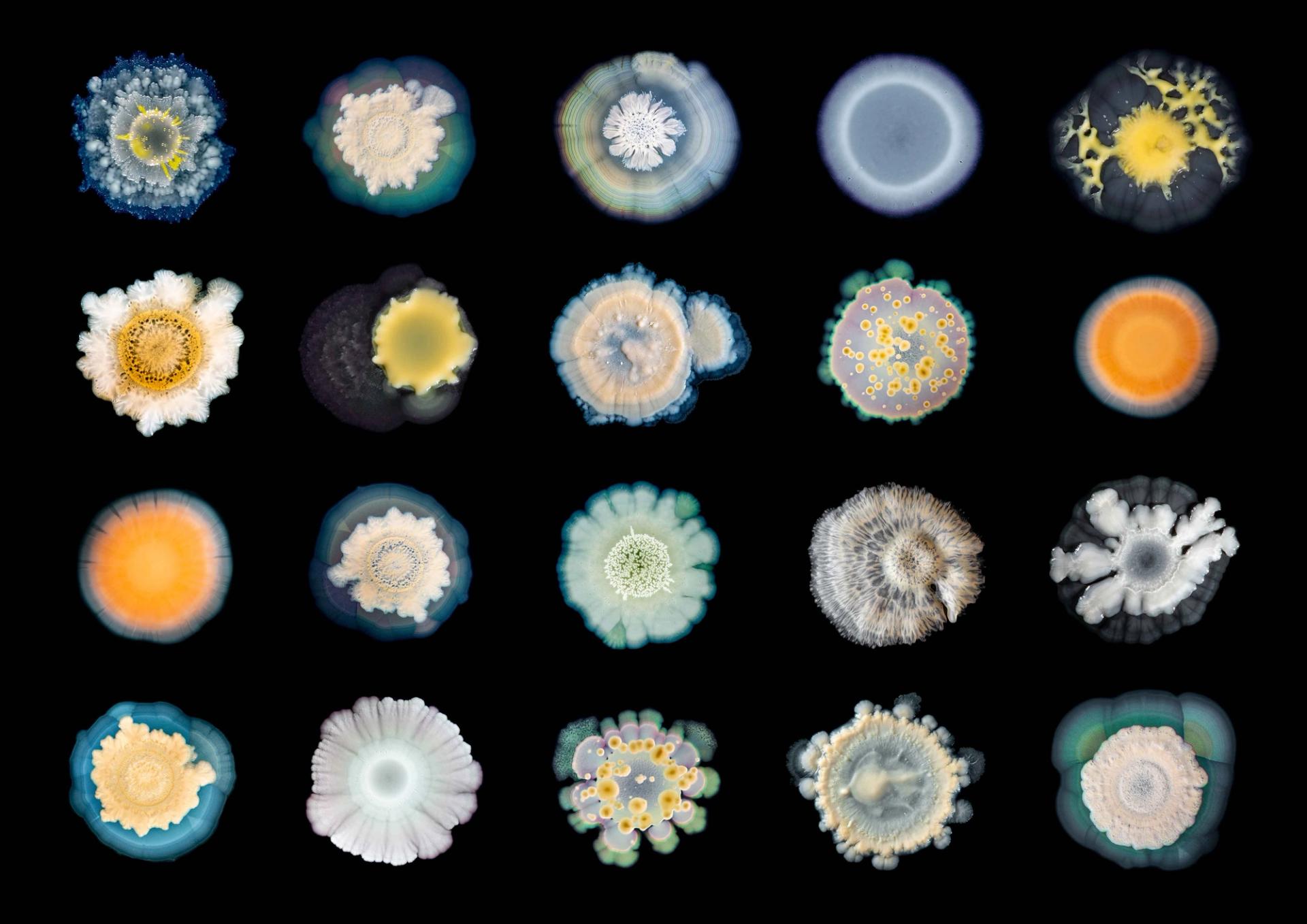

The importance of understanding our connection to earth is thrown into sharp relief by the show’s examination of the detrimental effect of human activities on the health of the soil, which then directly impacts the wellbeing of the world at large. Right at the beginning, amid the microscopic revelations in the show’s first galleries, there is a less benign beauty to be found in the grid of exquisitely blooming floral forms presented by the photographer Tim Cockerill and the micro-biologist Elze Hesse. These works depict swarming colonies of bacteria struggling to survive in Cornish soil that has previously been heavily contaminated by mining.

Tim Cockerill, A Diversity of Forms Courtesy of the artist

A significant part of the Somerset House exhibition then goes on to highlight the strong ties between soil condition, climate change, human health, social injustice and the need for regenerative farming practices. The designer Fernando Laposse, for example, has collaborated with members of the Mixtec community of southern Mexico, drawing on their knowledge of the agave plant’s ability to grow on and repair land eroded by agrichemicals. Laposse has created furniture and objects using sisal sustainably harvested from agave leaves, some of which is on show here.

The grim legacy of both colonial and commercial extraction is addressed in Analee Davis’s Sacharrum officinarum and Queens Anne’s Lace (2016), in which depictions of sugar cane regrowth symbolically meander over the neat columns of a 1970s paylist from the former Barbados plantation where the artist now lives.

Then there’s Asunción Molinos Gordo’s traditional-style Egyptian patchwork, featuring geometric patterns based on satellite views of the Nile Valley. Interrupting the multiple rectangular grids, which represent the naturally irrigated plots of local farmers, are the large overbearing white circular shapes of agri-business farms. These are owned by private companies servicing the international market and with close ties to the Egyptian government. Rather than using the seasonal waters of the Nile, they extract non-renewable water pumped from underground.

Vexed entanglements between land and people are the subtext of The Flowers Stand Witnessing (2024), a tender elegiac film by Greek Palestinian Theo Panagopoulous. It comprises found colour footage—captured by Scottish missionary settlers—of magnificent wildflowers growing in 1930-40s Palestine and the local people living among them. The artist sees this film as being of a lost time, albeit one in which the area was already being problematically occupied as “a form of testimony in a heightened and uncertain time, and of resistance to cultural erasure”. In Palestine today, these flowers may now be gone, but soil bears witness and also carries the potential for new growth.

Still from Theo Panagopoulos, The Flowers Stand Witnessing © Scottish Documentary Institute

For those lucky enough to have them, gardens offer a benign means to get up close and personal with soil. Howard Sooley’s tender film about the grand gardens of Great Dixter in Sussex, as well as Ken Griffiths’s 12 photographs of an elderly couple, taken every month throughout 1974 outside their small cottage garden in Kent, pay homage to this intimate human connection with the land.

Johanna Tagada Hoffbeck’s paintings also pay moving testament to a gardener’s small, fleetingly precious encounters with the earth: the curl of a cabbage leaf, the pressing of hands into soil, a brief encounter with a butterfly. Moments such as these are crucial reminders of all the life forms that soil supports and is supported by. And that includes all of us.

The soil is a living witness to all that we have done and will do. Both inspiring and informative, this important exhibition leaves us in no doubt that if we are serious about being able to continue living on this planet, soil is the place to start. It is the lynchpin of our world’s survival and there’s no time to lose.

- Soil: the World at Our Feet, Somerset House, London, until April 13