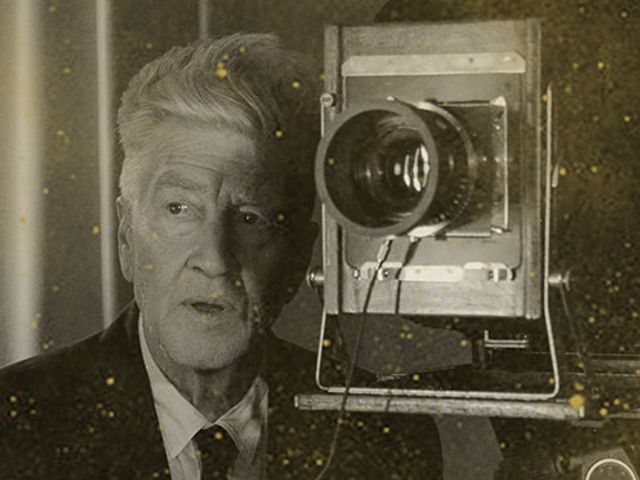

David Lynch—the artist and director known for films like Blue Velvet (1986) and Lost Highway (1997), and the television series Twin Peaks (1990-91, 2017)—died on Thursday (16 January) at age 78. His family announced his death in a Facebook post, but did not specify a cause of death.

“There’s a big hole in the world now that he’s no longer with us,” the family’s statement reads. “But, as he would say, ‘Keep your eye on the donut and not on the hole.’”

Lynch was best known for his work in film and television, which included the beloved early 1990s series Twin Peaks (which was revived for one season in 2017), and similarly endearing, foreboding, surreal, sometimes abruptly and brutally violent films including The Elephant Man (1980), Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart (1990), Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive (2001) and others.

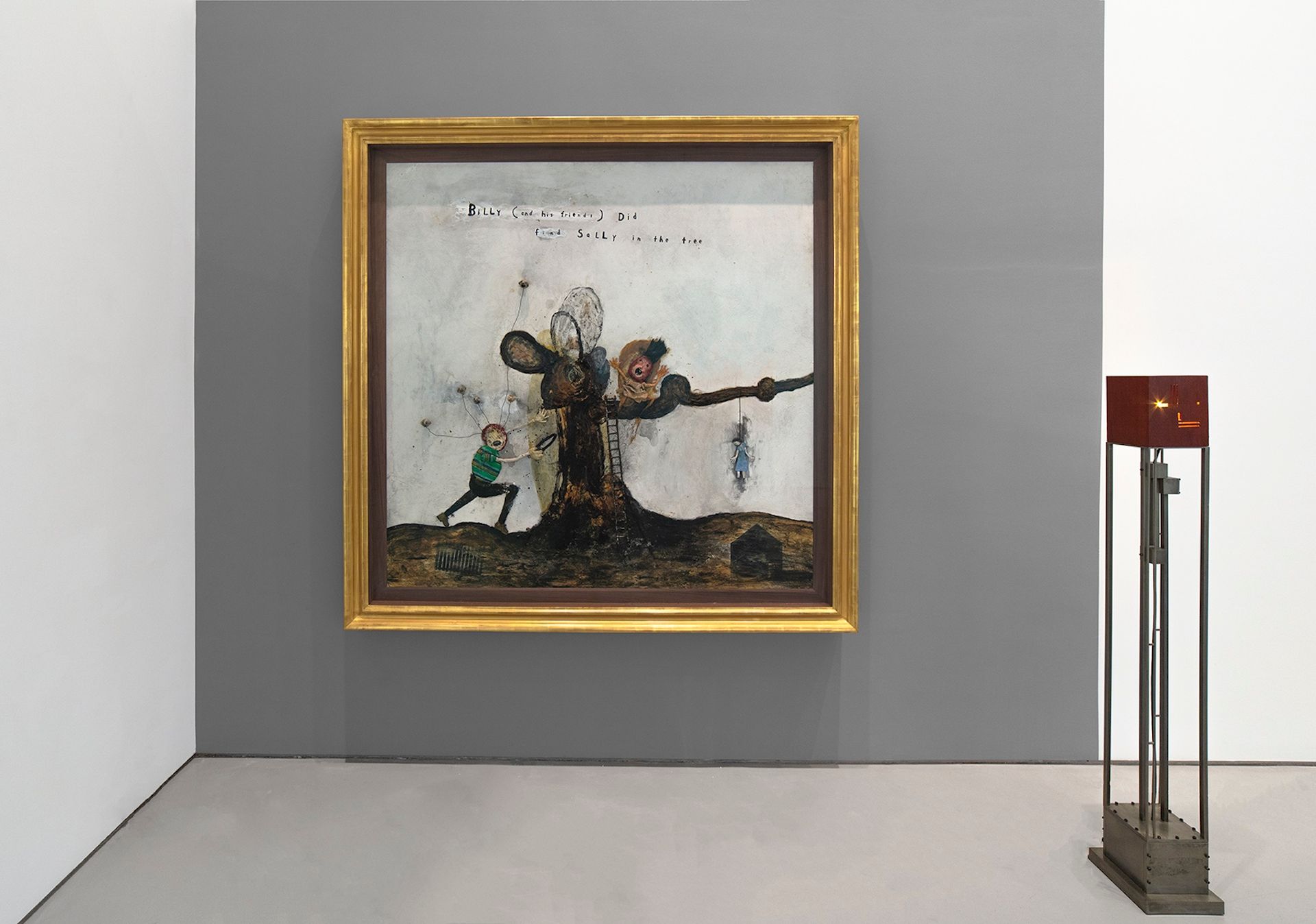

David Lynch, Tree at Night, 2019 Courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York

He was trained as a painter, and returned to that original passion repeatedly throughout his film-making career, including for high-profile solo exhibitions at the Fondation Cartier in Paris (in 2007) and his alma mater, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (Pafa) in Philadelphia (in 2014-15). In late 2022 he had concurrent New York solo shows at Pace and Sperone Westwater, the latter of which has shown his work repeatedly since 2019 (he was previously represented by Los Angeles’s Kayne Griffin Corcoran Gallery).

“It comes with the idea and it’s the idea that starts you, and then it’s this process of action and reaction,” Lynch said of the painting process at the time of his 2022 exhibitions. “This is the thing you hope to keep alive. And there’s got to be a freedom to say, that didn’t work, it’s got to go. Then in the process of destruction, a beautiful new thing can emerge...random things, random choices and then—bang, an idea comes.”

In a statement, Angela Westerwater, a partner at Sperone Westwater, said: “The world has lost a talented artistic visionary whose innovative and expansive mind enriched our view of the world. We are so fortunate to have hosted two solo exhibitions of David’s paintings, lamp sculptures and works on paper. He will be remembered through his groundbreaking creations. He was a true original and someone I was honoured to call a friend.”

Marc Glimcher, Pace's chief executive, said in a statement: "Anybody lucky enough to grow up during the prime Lynch years—the 1980s and 90s—had the architecture of their brain significantly rebuilt by his genius. What an unbelievable loss of a pure creator. Lynch turned insanity into philosophy."

David Lynch, Squeaky Flies in the Mud, 2019 Courtesy of the artist and Sperone Westwater

Lynch was born in 1946 in Missoula, Montana, and spent much of his adult life based in Los Angeles. As a teen he enrolled in art school, first at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, DC, then at the Boston Museum School and Pafa. While studying at the latter, in 1967, Lynch made the mixed media work Six Men Getting Sick, which incorporated elements of painting, sculpture, film, sound and installation. This served as the gateway for his engagement with film, which became his medium of choice for decades.

“I think Francis Bacon is my biggest inspiration,” Lynch told The Art Newspaper in 2008. “The organic phenomenon in his paintings and his use of space is incredible. I also like Basquiat, Schnabel, Kiefer, Baselitz and Freud.” He added, of his time studying at Pafa: “Philadelphia was my biggest influence. On one hand it was great because at the art academy there were some serious painters, and it was really thrilling. But Philadelphia itself was such a sick city and there was so much fear and absurdity there that it just seeped into me. At the time, I began making figurative paintings of mechanical women.”

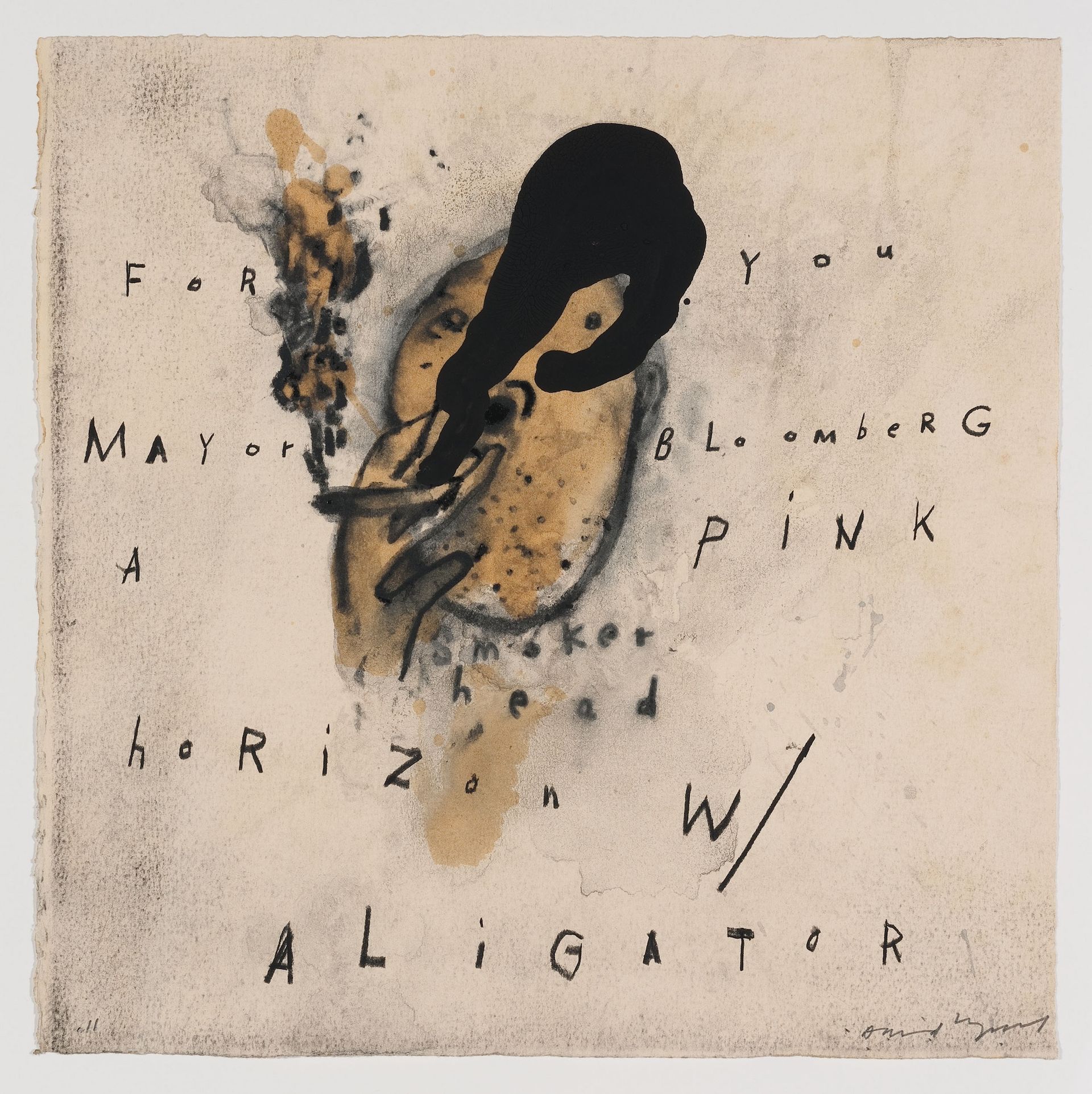

Many of his works on canvas have a dark, absurd energy, as well as a Baconian tinge in their distorted figures, stark palettes and aura of psychological dread. Many also incorporate fragments of text as well as sculptural elements.

David Lynch, Smoker Head, 2011 Courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater

In addition to painting and moving image work, Lynch pursued printmaking, sculpture and photography; in 2021-22, a survey of his photos traveled to institutions in Switzerland and Denmark. In photography, he told Time Out his biggest influences were William Eggleston, Joel-Peter Witkin and Diane Arbus on the occasion of a 2014 exhibition at the Photographers Gallery.

“The art life is a great life,” Lynch told Artforum in 2019. “It’s coffee and cigarettes, maybe some red wine. It’s catching ideas and translating them to one medium or another. In the world of painting it’s getting deep into that world and just getting lost in there—with paint and different things. And it’s just a dream to get in there and find things that you love.”

Lynch’s wide-ranging interests went beyond visual art, films and television. He also dabbled in interior design, helping to create Silencio, a nightclub in Paris based on a venue in his 2001 film Mulholland Drive. He had a sustained interest in music, releasing three solo albums and seven collaborative records between 1998 and 2024. He was also something of a coffee mogul, and like one of his most beloved television characters consumed many cups every day (he was also a heavy smoker for decades and ultimately developed emphysema, according to a post last year on X).

Installation view of David Lynch: Squeaky Flies in the Mud at Sperone Westwater in New York in 2019 Courtesy Sperone Westwater

“Since I was in high school, I read a book called The Art Spirit by Robert Henri, and in it he talks about this art spirit that transformed itself into the art life for me,” Lynch told Vice in 2014. “Coffee is part of the art life. I don’t know quite how it works, but it makes you feel really good and it serves the creative process. It goes hand in hand with painting for sure.”

Lynch was also a devoted practitioner and proponent of transcendental meditation from the 1970s onward. In 2005 he created the David Lynch Foundation for Consciousness-Based Education and World Peace, which continues to advocate for the practice’s benefits for war veterans, other survivors of traumatic experiences and the general public.

“Transcendental meditation gives me and everyone else access to a source of infinite happiness, love, energy and peace that exists deep within every person,” Lynch said in a 2018 interview with Coveteur. “It is hard to remember what I was before I started to meditate, but the anger I had before I started transcendental meditation is gone, and I do feel a great happiness and freedom in all the ‘doing’—in my work, in my life.”