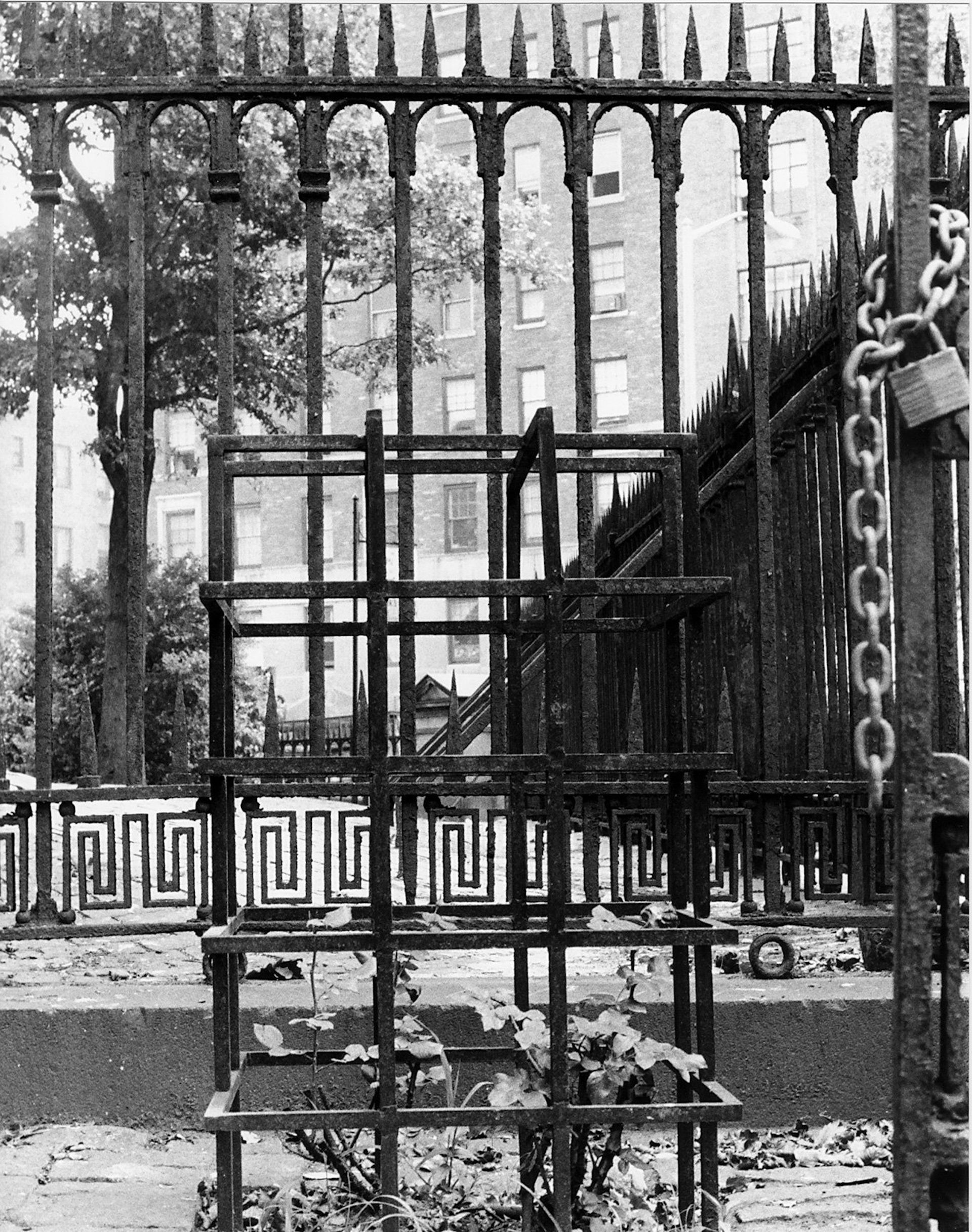

In a brief yet prolific career that ended with his death at age 35 in 1978, Gordon Matta-Clark responded to the neglect of New York City’s urban environment with radical interventions, most famously colossal cuts in abandoned buildings. Much of his work was meant to be ephemeral, and little of it survives, especially in the places it was created. An exception is a small, rusted steel cage outside St Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery in the East Village. For years it has stood unmarked and empty of the flowers it was intended to hold.

Last autumn, Rosebush (1972) was revived with a reactivation event to celebrate its new planting and plaque. The initiative was organised alongside Energies (until 5 January), a group exhibition at the nearby Swiss Institute that includes work by Matta-Clark and others who have engaged with local ecology in collaborative, community-based ways.

“While doing research for the exhibition, I came across Rosebush and the enclosure that I walk past almost every day,” says Stefanie Hessler, the director of Swiss Institute. “It was so striking to me that Gordon Matta-Clark had created this beautiful, very poetic piece and how different it is from the architectural interventions that he’s most known for.”

Community engagement in full bloom

Even now with its new rosebush, it is an incredibly humble piece, especially compared to works like Day’s End (1975), which sliced a gaping aperture into a decrepit pier on the Hudson River. In the tension between nature and a city of steel and concrete, Rosebush is reminiscent of the artist’s earlier planting of a cherry tree in the basement of the art space 112 Greene Street. From one view, its rectangular cage can be seen as attempting to contain an unruly nature; from another, it shelters the rosebush in a city where nature has been pushed to the margins.

“It is, we believe, the only existent work in an outdoor public space of Gordon’s,” says Jessamyn Fiore, co-director of the Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark.

Matta-Clark led a crosstown procession to the church, where he ceremoniously planted his Rosebush and came back later to install the gridded cage around itFrances Richard, author, Matta-Clark: Physical Poetics

The reactivation event was a collaboration between Swiss Institute, the Poetry Project, Danspace Project and St Mark’s Church. The inclusion of readings and performances was a nod to Matta-Clark’s engagement with the St Mark’s creative community in the 1970s as well as the work’s performative roots. In her book Gordon Matta-Clark: Physical Poetics, Frances Richard writes: “Matta-Clark led a crosstown procession to the church, where he ceremoniously planted his Rosebush and came back later to install the gridded cage around it.” Previously, in 1970, he had built his first Garbage Wall at St Mark’s, inviting people in the neighbourhood to join in collecting trash from its streets and turning it into a structure that he envisioned as a prototype for temporary housing.

Photograph of Gordon Matta-Clark's Rosebush (1972) Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner

“Rosebush was a smaller work in a constellation of projects where he moved through ideas about the lived environment and how the people of New York can not just reclaim their environment, but transform it in a way that meets their needs and betters their lives,” Fiore says.

His civic-minded, hands-on practice was embedded in a greater movement in the neighbourhood to fill gaps in an underserved city. Energies also spotlights a rooftop wind turbine installed by the sweat-equity co-op at 519 East 11th Street in 1973. The project supplemented local electricity amid cuts and outages and, in a pivotal case brought against it by Con Edison, supported the existence of non-utility energy generators.

“It was really important—in the spirit of 519 East 11th Street—to have a collective neighbourhood and community-wide approach to the exhibition,” Hessler says. “Rosebush and the replanting are part of that ethos, where it was important to us to propose a small intervention that will have a long-term existence in the neighbourhood. It became a way to revisit history, as well as certain ideas regarding community and the environment and housing and all of these issues that are still so very pertinent and important in the neighbourhood.”

The plaque now accompanying Rosebush—located to the left of the church steps—foregrounds that history, noting that as “a socially engaged artist, [Matta-Clark] was deeply involved with the Lower East Side and East Village communities”. Energies includes a black-and-white 1970s photograph of Rosebush alongside Matta-Clark’s Energy Tree drawings of abstracted arboreal shapes that radiate with a feral kineticism, and his proposal for a community centre where local youth could learn to transform abandoned sites into gardens.

“One of the reasons why he’s still so influential is because his practice was an inherently generous one,” Fiore says. “It invites others to respond.”