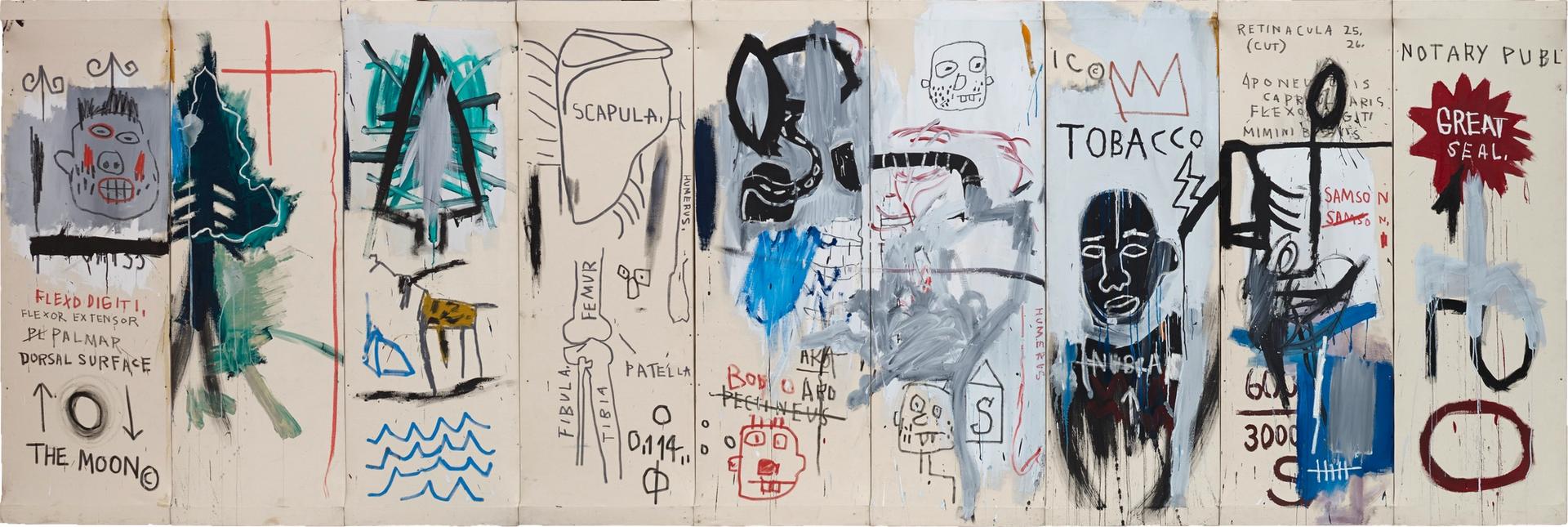

In The Dutch Settlers (1982), Jean-Michel Basquiat splices markers of historical exploitation ("TOBACCO"), the birthplace of African civilisation ("NUBIA"), and religious references ("SAMSON") with a drawing of an ibex, the megafauna of the Engadin region of Switzerland.

The monumental nine-panel painting is the stand-out work of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Engadin at Hauser & Wirth St Moritz (until 29 March), the first exhibition to focus on Basquiat’s relationship with the Alpine region.

The loans-based show has been put together with the help of the curator Dieter Buchhart, a Basquiat scholar who has organised exhibitions such as Jean-Michel Basquiat: Made in Japan, held at the Mori Arts Center Gallery in Tokyo in 2019. That exhibition looked to assess the artist’s relationship to Japan; the other major country that Basquiat frequented during his short life—Italy, and especially Rome and Florence—is surely next in Buchhart’s sights.

Jean-Michel Basquiat's The Dutch Settlers

© Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New YorkNicola Erni Collection. Photo: Reto Pedrini Photography

Sometimes the format of “x artist abroad” can feel a little forced, often curated to artificially engineer new audiences or markets for their work. But Basquiat’s time in the Engadin is a genuine blind-spot in our understanding of one of the most studied artists of the post-war period.

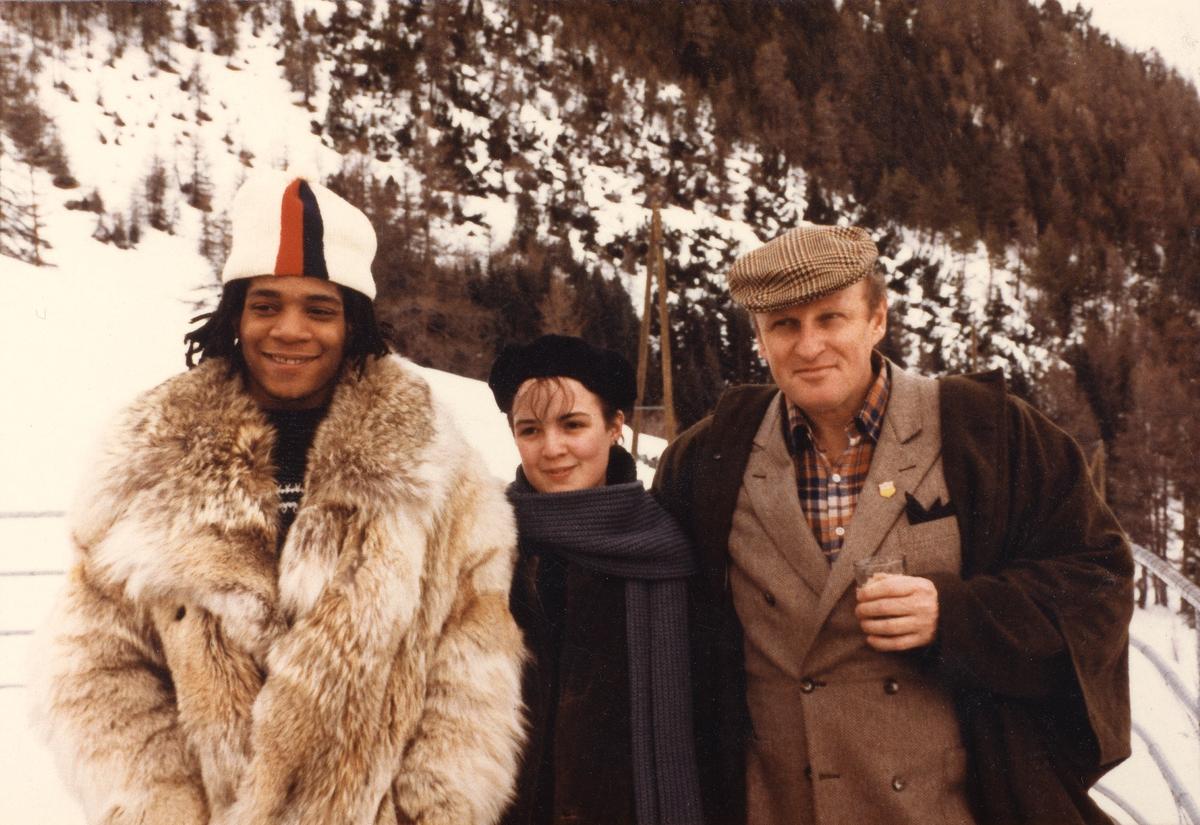

Remarkably, after the Swiss dealer Bruno Bischofberger visited Basquiat in his Crosby Street studio and immediately became his exclusive worldwide representative in May 1982, the artist left the grit and grime of the Lower East Side for the pristine chalets of Switzerland a total of fifteen times. That included around half a dozen visits to Zurich and seven to St. Moritz, four in the summer and another at Christmas, when he was guest of honour with his dealer’s family in their mountainside estate. (As a Christmas gift for each family member, Basquiat presented one of the paintings he had made in the Stockholm studio of the Norwegian artist Knut Swane).

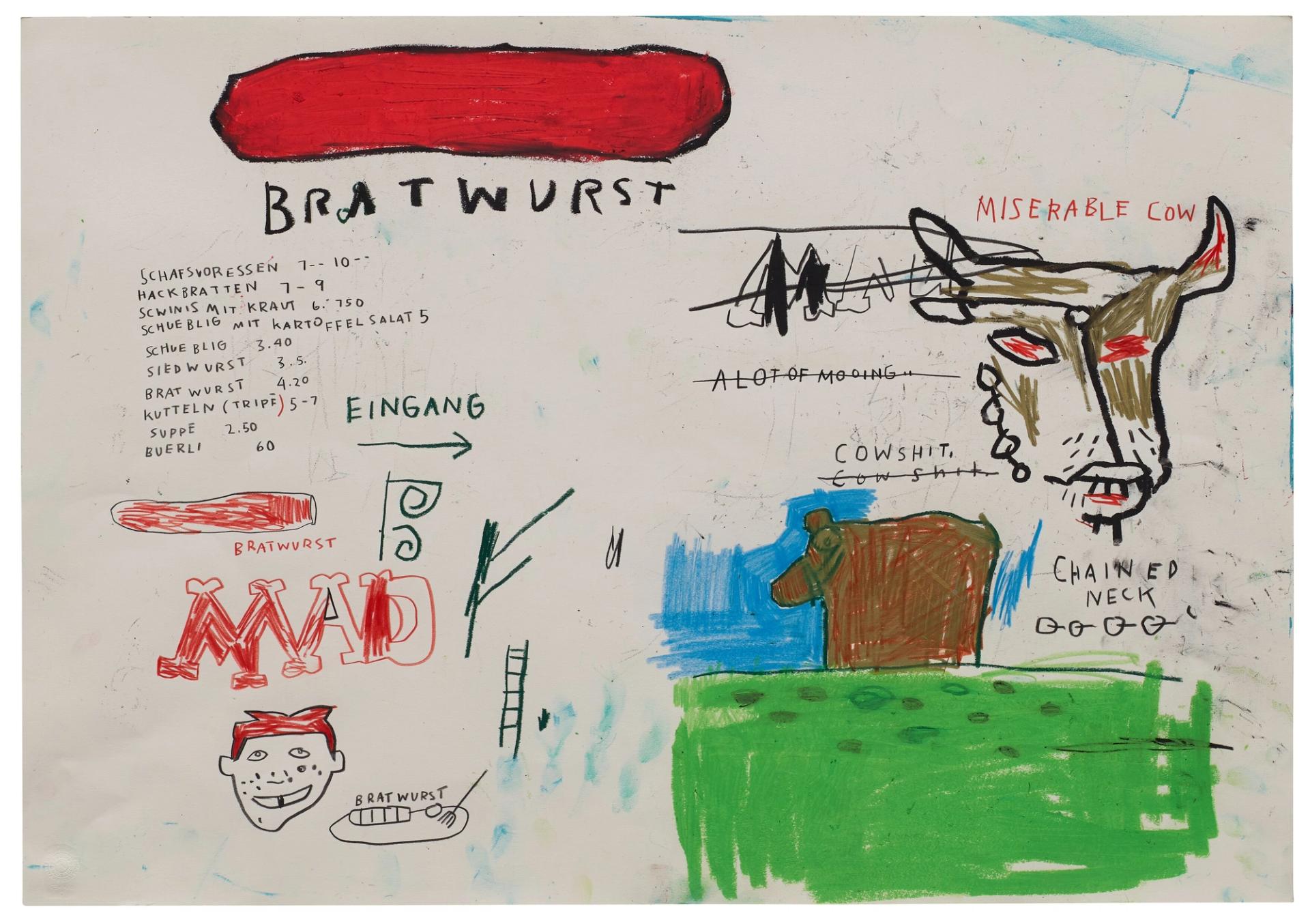

Basquiat became fascinated by the change of pace in the Alps. He went cross-country skiing and visited the Toggenburg Bull Show, where traditionally dressed farmers would proudly display their best bulls. He was fascinated by stag’s antlers and chamois. He ate bratwurst and drank Appenzeller pilsner. Many of these local flavours found their way into Basquiat’s ever-expanding lexicon of icons and pictograms: depictions of phallic red sausages are represented alongside the scrawled word “COWSHIT” in Bull Show Three and Four (both 1983); a loose sketch of a maudlin show bull in a harness emphasises the oppressive bondage of the animal; while Appenzeller Alpenbitter (1983) sees a majestic black bear, the beer’s emblem, on its hind legs while the thinned trees and cottages of the snowy Wildkirchli mountain range stretch out behind.

Jean-Michel Basquiat's Bull Show Two (1983)

© Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New YorkBischofberger Collection, Männedorf-Zurich

But Basquiat’s time in Switzerland was not all hearty grub and leisure time. While in New York his experiences of racism were acute and terrifying, as police used violence to intimidate young Black men and, as in the 1983 case of Michael Stewart, to kill them, his encounters in Switzerland spoke to a kindly antagonism in which he was the exotic object of fascination. When Bischofberger took Basquiat to visit his friend, Claudio Caratsch, an ambassador to four African countries, Caratsch lectured Basquiat on how African artists sought to use art “to repel ghosts.” Basquiat incorporated these words onto three sequential works: the first, on a found object support, in full legibility, and in white on black and his “TM” copyright logo; the second two, on a blue background, sees the words redacted until they are indecipherable. Often what Basquiat erases is the place where he most wants us to look. In another extraordinary work, Big Snow (1984), Basquiat links the Swiss mountain ranges to the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, where Jesse Owens’ decisive victories in track and field were overshadowed by Adolf Hitler’s refusal to award his four gold medals. The spectre of racist violence haunts these pictures.

The exhibition also foregrounds the importance of collaboration in Basquiat’s practice. After flying with the Bischofbergers (both parents and all four children) by private jet from St. Moritz to Ancona in Italy, and then on to Rome, Basquiat met up with Francesco Clemente, another Bischofberger charge, and it was there that they discussed and titled the fifteen works that the two artists, together with Andy Warhol, had made “together” back in New York. The series was a surrealist-inflected cadaver equis, where the works skipped through their respective studios as each artist added their own contributions. One such work on display in St Moritz, Bianco (In White) (1984), is a fascinating account of three idiosyncratic artists hemmed into the same canvas, vying for space. Another––far less well-known––collaboration is an untitled work made by Basquiat and Bischofberger’s three-year-old daughter, Cora. It reminds us of the unbridled joy in so many of the artist’s works, as well as how they resemble what Basquiat described, on first meeting Bischofberger in New York, as his greatest influence: “works by very young children.”

• Jean-Michel Basquiat: Engadin, Hauser & Wirth St Moritz, until 29 March