Marc Camille Chaimowicz’s multi-faceted practice, spanning over five decades and encompassing installation, performance, painting, artist books, and furnishings, defies categorisation, writes Melissa Blanchflower. It inhabits a space uniquely his own—where there is a porosity between art and design, public and private, and feminine and masculine. The art critic Jean Fisher wrote that his work is “the nature of a journey, an epic poem that recounts a quest not through dramatic actions and gestures but through a modest and tender exploration of the microcosmic world of everyday experience”.

An artist who evaded revealing his year of birth (it was post-war Paris) and kept many details of his life private, Chaimowicz produced work that is inextricably autobiographical. Born in France, he moved with his family to England when he was eight, first to Stevenage, in Hertfordshire, and then London. He studied at Ealing Art College and Camberwell School of Art. The May 1968 student demonstrations he witnessed in Paris were a catalytic experience and profoundly affected him. On returning to London to start his master's at the Slade School of Fine Art, he destroyed his paintings (a medium which would resurface years later through his wallpapers and textile designs), setting his practice on a new course.

Chaimowicz emerged on the London art scene in the early 1970s with his groundbreaking “scatter environments” which were charged with political and feminist discourses of the time. Imbued with possibilities, these floor-based, room-sized installations could have been a stage poised for performance or the aftermath of a party. Visitors to Celebration? Real Life (1972) at Gallery House in London could converse and drink tea with the artist living there. It signalled the beginnings of Chaimowicz’s preoccupation with the relationship between art, life and décor.

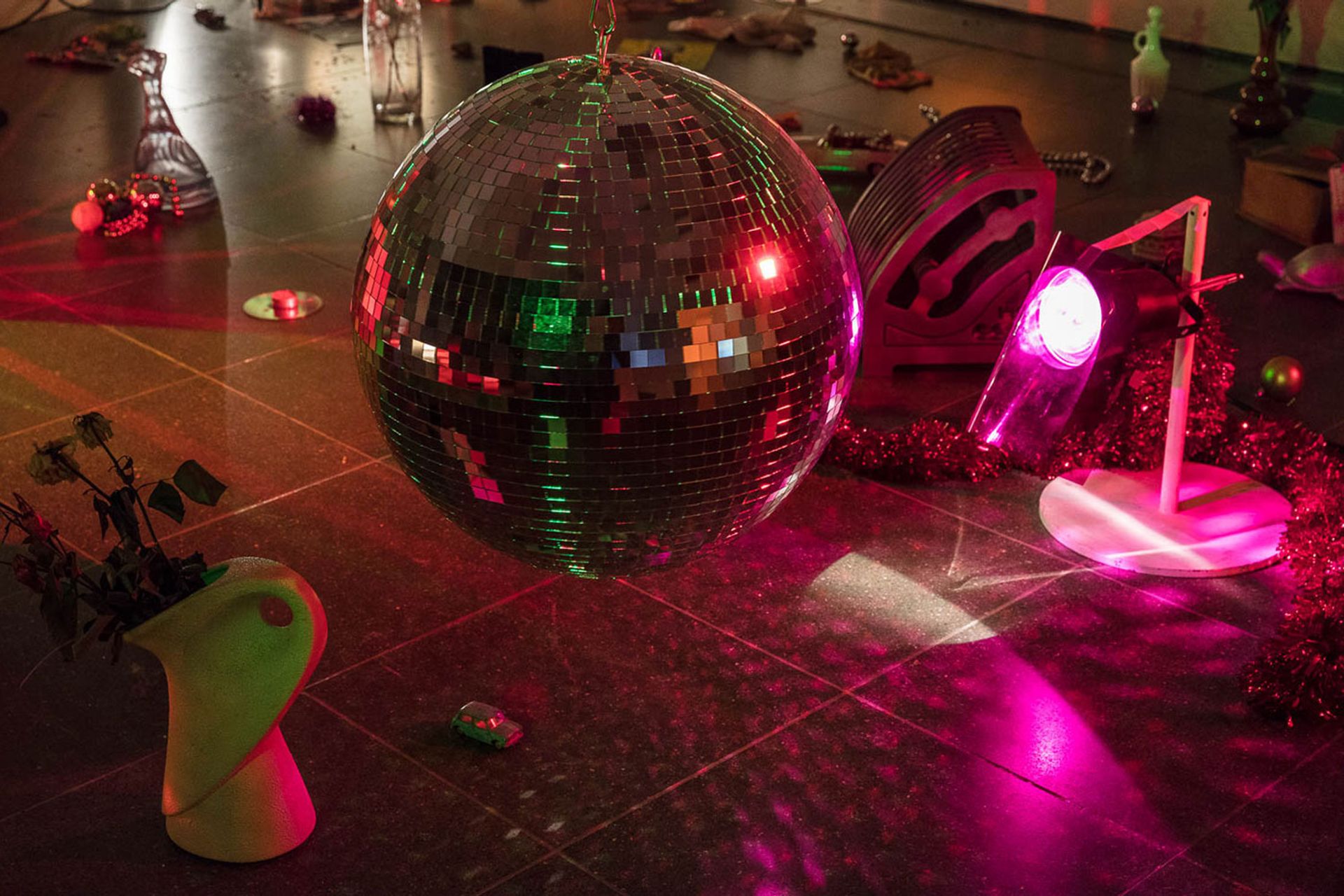

“Scatter environments” charged with political and feminist discourses: Marc Camille Chaimowicz, Installation view, An Autumn Lexicon,Serpentine Gallery, London, 2016 Courtesy the artist and Cabinet, London. Photograph: mark@markblower.com

When I curated Chaimowicz’s 2016 Serpentine exhibition An Autumn Lexicon, we restaged its “sister” installation, Enough Tiranny (1972), in the gallery where it had been first presented. This move mirrored Chaimowicz’s tendency to revisit and recontextualise his past work, with a subtle Proustian reference, evoking the passage of time and the way memories shape our understanding of art. Sharing many overlaps with Celebration? Real Life, Enough Tiranny combines art historical references with glam rock popular culture. A silver-painted wall, reminiscent of those in Andy Warhol's Factory, is emblazoned in black lettering with the work’s title containing a deliberate spelling error. This subtle slip was loaded with political significance: the letters “ira” were concealed in the word, referencing the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the ongoing Troubles in Northern Ireland during that time. Comprising everyday objects such as vases of cut flowers, records and glitter, it is lit by strings of fairy lights strewn on the floor, coloured stage lighting and a hint of daylight filtering through curtains he made—a nod to Felix Gonzales-Torres whose curtain had hung across the same windows in 2000. The disco aesthetic was further enriched with a revolving disco ball, the sound of trickling water from indoor ponds with fish, and a soundtrack. Its scattered nature and open-ended composition invited the audience to wander through the work and experience it as a live space.

These strewn and colourful installations generated intimate and participatory experiences. stood as stark counterpoints to the austere and intellectual trends of Post-Minimalism and Conceptualism which dominated the 1960s and 70s. Chaimowicz anticipated immersive installation art that would become dominant in later decades. He opened up the possibilities for artists to experiment with tableau and performance. Much to his delight, in 2016, The Guardian called Chaimowicz the “godfather” of contemporary conceptual art, noting that today this is often driven by emotional resonance and popular culture—qualities that Chaimowicz had already embedded in his work decades earlier.

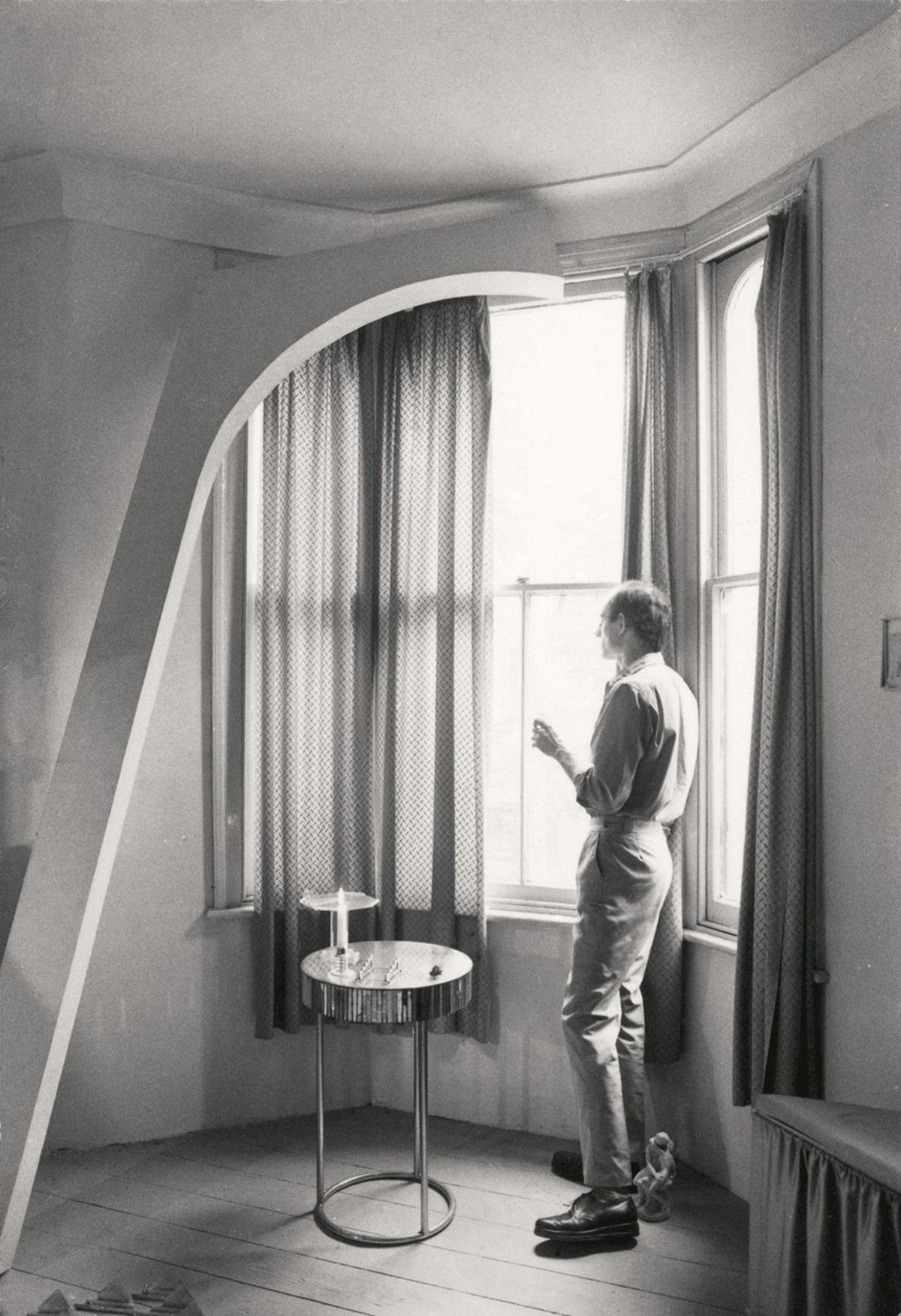

In the mid-1970s, Chaimowicz’s focus shifted inwards towards the home when he began designing his apartment on Approach Road, east London, a project he worked on from 1974 to 1979. His aesthetics changed from a glam rock sensibility to pre-war modernism, yet still interlocked with the same themes and preoccupations. The home was captured in a black-and-white photograph of the artist looking through a window. This image and the arch propped in front of him appear in various forms across his work, acting as a recurring motif that evokes memories and the passage of time. The blurring of life and art continued at Hayes Court, an apartment block in Camberwell, where he lived with his furnishings and prototypes for 40 years.

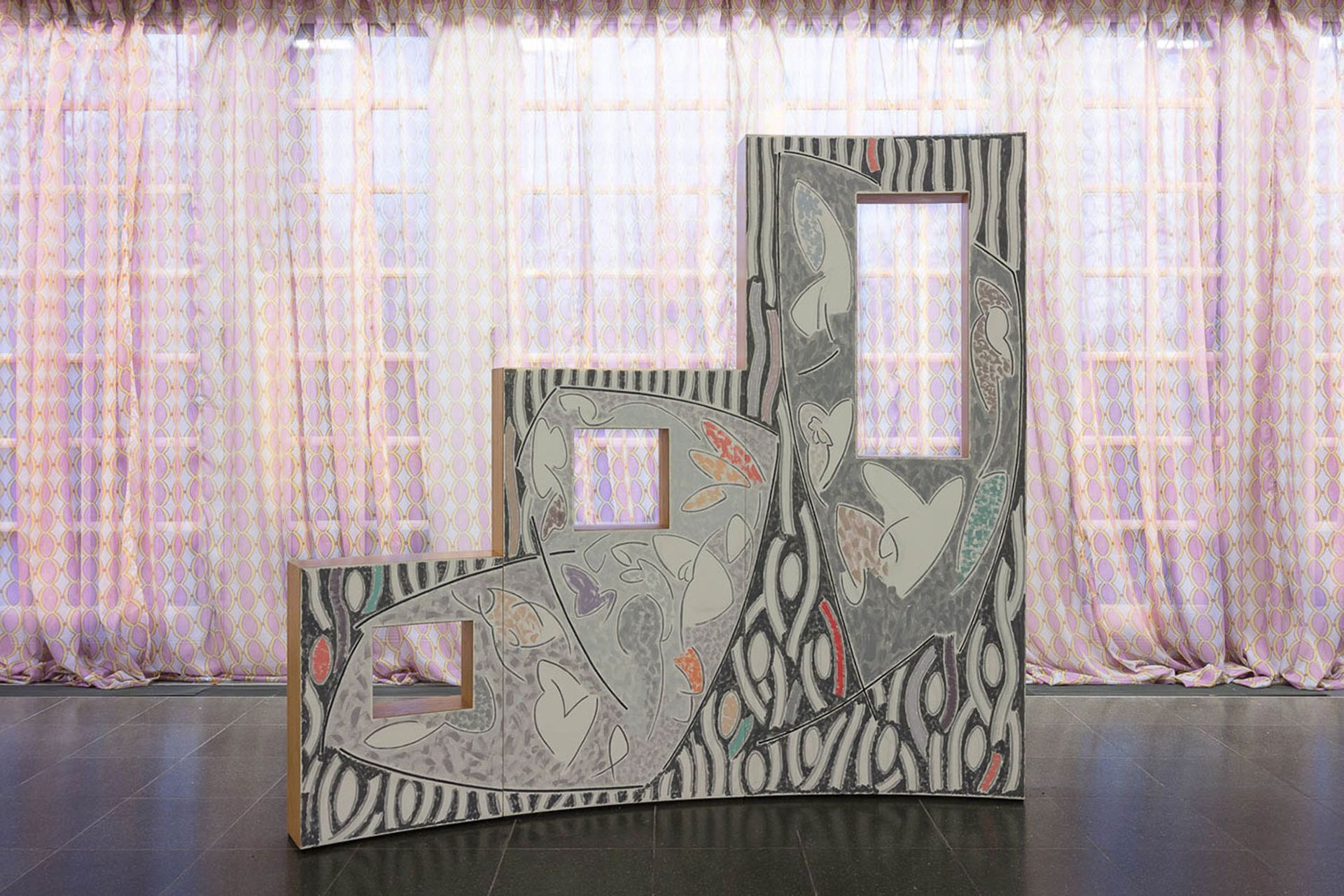

Marc Camille Chaimowicz, installation view, An Autumn Lexicon, Serpentine Gallery, 2016. Works shown (left to right): Man Looking out of Window (for SM) (2006); Child’s Chair (1989–2013); Bibliothèque (pink) (2009); Complete works of Gustave Flaubert (2014) Courtesy the artist and Cabinet, London. Photograph: mark@markblower.com

For Chaimowicz, domestic objects and interiors were heavily invested in cultural, literary, and biographical references. Responding to the Serpentine’s domestically-scaled architecture and history as a 1930s tea house, he arranged an upright chaise longue, paravents, lighting fixtures, bureaus and dressing tables, as well as rugs and wallpapers as an expanded mise-en-scène—taking on the form of an ever-shifting still life. He made temporary interventions too: a proposal for a frieze in the oculus of the first space, bringing our attention to the overlooked ceiling window and a large mural reflecting a stylised parkland. He harnessed the intense morning light by covering a window with gels that cast coloured lozenges on the floor and walls, which change and move throughout the day, echoing the artificial disco lights used in the adjacent gallery housing Enough Tiranny.

Chaimowicz often invited a cast of literary figures and artists to inhabit his creative space. Drawing inspiration from them as if they were members of his imagined extended family, Jean Cocteau, Madame Bovary, Marcel Proust, and Jean Genet reappear throughout his work, underscoring how French cultural history shaped his practice. Opening his spaces to others is a gesture of generosity and homage, reflecting his belief that artists never work in isolation. At Serpentine, he “invited” Eduard Vuillard’s Interior with a Screen (1909-10)—a painting that resonated deeply with his interest in décor and intimate space. The choreographer and dancer Michael Clark made a video of the sun setting and rising through the panoramic windows of his rehearsal studio, further adding a layer of movement, time, and light transition to the exhibition. These works, alongside Chaimowicz’s own, hint at the intersection of his French and Anglo identities, blending the influences of 20th-century French art with contemporary London culture. During the installation's final hours, Chaimowicz “invited” another—David Bowie—who had passed away earlier in 2016. Although a wide range of musicians and bands usually made up the work’s soundtrack, this time only Bowie's records were played in homage to the iconic artist. This act further emphasised Chaimowicz's tendency to weave his personal influences, cultural touchstones, and friendships into his art, acknowledging the interconnectedness of his own identity with the broader cultural landscape.

For his final exhibition at Cabinet in London which closed on 18 May 2024 a few days before his death, Chaimowicz arranged his Décors Textile Studies (1983) and fabric work Cascade (2020) in dialogue with sewing exercises made by his mother Marie Tailhardt, a seamstress who had worked at the prestigious house of Paquin in Paris before he was born. Chaimowicz intertwined his own artistic practice with the craftsmanship and history of his mother, forging a link between familial legacy, the artisanal and his ongoing exploration of design and memory. The exhibition began with a photograph by Lee Miller of Victory Celebrations at Maison Paquin (1944), an image frozen in time at the end of the Second World War. Connecting these narratives, we imagine his mother is just out of frame. Chaimowicz’s choreography of fabrics and images in this exhibition unfolded as a mediation on family, place, remembrance, déjà-vu and time, a poignant conclusion to his remarkable career.

Chaimowicz with one of his murals at his exhibition An Autumn Lexicon, Serpentine, London, 2016 Photograph: Melissa Blanchflower

“As I sailed past on my bike, I would spot him cutting a dapper dash at the bus stop, in trademark trilby and an elegant (often Missoni) scarf”

Marc Camille Chaimowicz was a friend and a neighbour as well as an artist whom I hugely admired, writes Louisa Buck. I greatly miss the evenings we spent consuming quantities of cigarettes and red wine which fuelled a heady brew of gossip and exchange of thoughts, made all the richer by Marc Camille’s courtly conversational style and gloriously mellifluous voice. For many years early January was greatly alleviated by the arrival of a small card embellished with an exquisite composition of Marc Camille motifs—a rose, maybe some grapes, a bow, a tassel, a scattering of his distinctive boomerang-shaped curlicues—printed on coloured card and meticulously hand-tinted before being sent out to wish a fortunate few of us “Mes Meilleurs Voeux” for the coming year.

I still find it hard not to look up at his third-floor window in Hayes Court, and the flat that became a fully fledged artwork in its own right, and see him smoking and perusing Camberwell New Road. Or, as I sailed past on my bike, I would spot him cutting a dapper dash at the bus stop, in trademark trilby and an elegant (often Missoni) scarf.

I can’t recall exactly when I first met Marc Camille, it was definitely in the late 1980s and probably through either the academic art historian Roger Cook or the great critic and curator Stuart Morgan, both mutual and now also sadly deceased friends. But I do remember the first time I consciously encountered his work. It was in 1984 when I was doing an MA at the Courtauld Institute, in London. I wandered into Liberty’s luxury department store and came across Four Rooms, the Arts Council Touring exhibition of four environments commissioned from Anthony Caro, Howard Hodgkin, Richard Hamilton and Marc Camille Chaimowicz. (Imagine ACE funding such a show in such a setting today!)

Marc Camille Chaimowicz, installation view, An Autumn Lexicon, Serpentine Gallery (2016). Works shown: Monaco for East (2014-16), background; Festivity (1987) Courtesy the artist and Cabinet, London. Photograph: mark@markblower.com

Here Marc Camille had created an extraordinary theatrical and deliberately camp mise-en-scène that played with and off conventions around domesticity, décor, taste, ornament and design in ways I had never seen before. A set of odd custom-made furniture—a desk, a couch, a room divider—was painted a chilly grey-blue to match the walls and tilted at strange angles that seemed to strike almost human poses. There was a stretch of wallpaper scattered with decorative calligraphic shapes in pastel shades of pink, green and yellow, a pattern repeated in the fabric covering a minimalist couch, while more fragmented forms shone out from a rectangular strip of stained glass set high into a wall. On a cartoonish angled screen protruding from a stalk in the wall a sequence of slides depicted a glamorous young couple lounging in the same interior, smoking, drinking wine, but never actually meeting each other’s gaze. Completing this louche but immaculate setting was an Eileen Gray tube lamp and one of her rugs, along with a pair of Art Deco vases. For me this was completely new and uncharted territory in the way that it messed with the strictly siloed worlds of art and craft I was just beginning to explore.

Now—and in large part due to the influence of Chaimowicz—it is commonplace for artists to dissolve boundaries between art and design as well as public and private; but he blazed a trail with his erudite embracing of the decorative and the domestic. “Domesticity became a sort of metaphor for me,” he told me in what turned out to be his last interview that he gave last year shortly before opening two solo exhibitions, in Weils in Brussels and in MAMC+ in Sainte Etienne—the latter Chamowicz’s first institutional show in his native France. “Colour was seen as decadent and pleasure as reactionary, and for me that had to be re-calibrated,” he explained. And, with his distinctive off-kilter pastel palette and in his lifelong dedication to calme, luxe and volupté he did just that.

Chaimowicz’s French cultural heritage remained crucial to him. The intimate interiors of Bonnard and Vuillard, the effete dandyism of Jean Cocteau and the writings of Flaubert, Jean Genet, and Marguerite Duras, amongst many others all infused his work. For many years Chaimowicz divided his time between Camberwell and the gatehouse to a château a half-hour to the east of Dijon, and I’m just so glad that shortly before he died I got to visit this town that he loved so much and which seemed infused with his spirit and even his palette. Here several wonderful rooms of his work were on show until early November in Le Consortium, including many pieces donated by Marc Camille to the museum, all brought together in an exhibition called, appropriately, A gift, with love.

Marc Camille Chaimowicz; born near Paris 25 January 1946; died London 23 May 2024