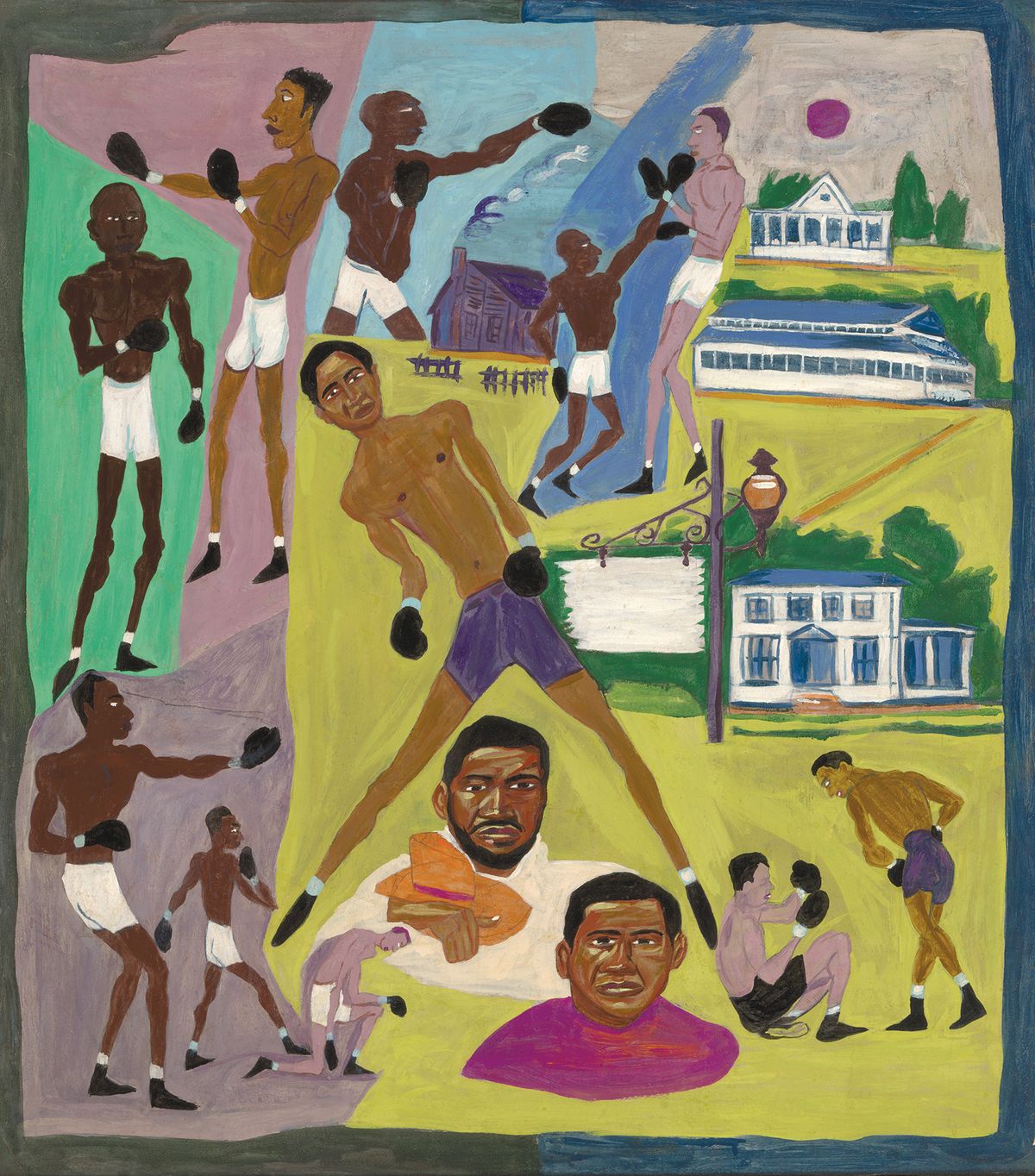

The Harlem Renaissance artist William H. Johnson’s prescient, social justice-forward final series of paintings is a testament to courage. Fighters for Freedom, organised as a touring exhibition by the Smithsonian American Art Museum curator Virginia Mecklenburg, features 29 portraits of change-makers—including Black scientists, singers, educators, activists, musicians and international leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture. This is the first time that Johnson’s Fighters for Freedom series has been shown together as a single body of work, according to Mecklenburg, who adds that the artist had a deep understanding of the international connotations of the fight for freedom.

In search of artistic freedom

Johnson was born in 1901 in Florence, South Carolina. He led a Bohemian life, escaping poverty by hopping on a bus to study art in New York during the Great Migration. After living in Harlem, he followed a long tradition of Black artists who left the US for Europe in search of artistic freedom. He lived on the Continent for about a dozen years—first as an art student in Paris and later in Denmark, where he married the artist and weaver Holcha Krake in 1930.

Krake’s interest in Danish folk art influenced Johnson’s signature style, which was described at the time as “modern primitive”. Johnson’s subject matter was inspired by his full embrace of his Black Southern roots after returning home from Europe in 1938.

Self-Portrait with Pipe (around 1937) was painted towards the end of Johnson’s time in Europe Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation

His painting Harriet Tubman (around 1945) is indicative of his narrative, Modernist style, characterised by simple forms and vibrant, flat colours. He places the legendary abolitionist in the centre of the painting holding the shotgun that she always carried (as she told enslaved fugitives who tried to turn back: “You’ll be free or die”). She wears a blue jacket, and her skirt has red-and-white stripes—a clear allusion to the US flag. Her figure is surrounded by colourful, abstract brushstrokes that resemble the metaphorical train tracks of the Underground Railroad. Johnson’s depiction is informed by both his study of wood and linoleum cuts and his interest in African sculpture.

Johnson offered an important counter-narrative, showing how much African Americans had contributed to the nation’s historyLonnie G. Bunch III, Smithsonian Institution

Countering racist stereotypes

“During the 1940s, images of African Americans were often negative, a collection of racist stereotypes intended to minimise Black people and rob them of their humanity,” says Lonnie G. Bunch III, the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. “Johnson offered an important counter-narrative, showing how much African Americans had contributed to the nation’s history.”

Despite Johnson’s pivotal contribution, his work faded almost into obscurity. In 1944, his life took a tragic turn when the death of his wife led to an irreversible decline in Johnson’s mental health. He was admitted to a state hospital in Islip, New York, in 1947, where he remained for the final 23 years of his life. After the artist’s death in 1970, his friends salvaged his work—which had nearly been thrown out because of unpaid storage bills.

• Fighters for Freedom: William H. Johnson Picturing Justice, Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum, Miami, Until 5 January