When the artist Liz Cohen discovered the Trabant—an East German car built for efficiency whose popularity crashed as the communist government collapsed—she recognised herself within it. Here was an object that represented the complexity of her own background: born in the 1970s to a Colombian mother and Colombian Jewish father whose political views often aligned with socialist and communist ideals, Cohen had always grappled with the parts of her upbringing that seemed contradictory and impacted whether she was perceived as belonging. Going deeper into this personal exploration of identity, Cohen purchased a Trabant in 2002 and began Trabantimino, a decade-long art project in which she installed an expanding hydraulics system that combined the car with a 1973 Chevrolet El Camino, resulting in a custom vehicle that launched her into the low-rider scene of the American Southwest.

“When I started doing the work with the Trabantimino, I wanted to take something that didn’t belong and find its way into belonging,” she says. Something that, on the surface, doesn’t have the right characteristics to be a part of something, that figures out how to be a fringe member.”

Cohen’s Trabantimino is on view at Pérez Art Museum Miami (Pamm) as part of Xican-a.o.x. Body (until 30 March 2025), a monumental exhibition of more than 150 works by 70 artists and collectives rooted in the Latinx community, organised by the museum’s chief curator, Gilbert Vicario, alongside Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Marissa Del Toro. Though the exhibition’s title suggests an investigation of Chicanx culture specifically, the curators purposely made the decision to include artists from numerous Latinx backgrounds.

“Part of the reason why Chicano art has been so misunderstood and so overlooked is because it didn’t really open its eyes to other possibilities,” Vicario says. The decision to include artists like Cohen, Mario Ayala and others who do not identify as Chicanx aligns with the curators’ intent to bring more visibility to this community of artists by taking an inclusive approach and demonstrating that even when belonging does not come naturally, it can be built.

“What the exhibition does is that it allows us to embrace a wider framework for identity and recognise that we don’t all fit neatly into one category,” Vicario adds.

Perceptions about who fits neatly into one category or another are part of what has made labels like “Latinx” and “Chicanx” so divisive among US-based artists with origins in Central and South America and the Caribbean. The value of the term Latinx was hotly contested during the Latinx Art Sessions, a two-day symposium hosted by Pamm in 2019. Was the term Latinx a platform designed to help artists gain increased exposure and find mobility within the art market, or was it a tool to further erase the differences between the experiences of artists from Spanish-speaking populations? At that time, artists and scholars like Daniel Joseph Martinez, Fajardo-Hill and Vicario were reluctant to adopt the term, but for many, that has changed in the past five years.

“For myself, personally, from over the course of that conference and up to this point, I really relaxed my position,” Vicario says. “It aspires to embrace many different identities, and it makes the conversation much more interesting.”

Mary Thomas, a programme officer at the US Latinx Art Forum (USLAF), suggests that organising under the term Latinx has led to increased visibility for artists. USLAF was formed in 2015 with the goal of supporting under-represented artists through grants and opportunities.

“We’ve had some incredible moments in the last decade,” Thomas says, pointing to the Xican-a.o.x. Body exhibition and travelling retrospectives by Latinx artists like Amalia Mesa Bains, Christina Fernandez and Celia Álvarez Muñoz as signs that exhibitions championing Latinx artists are being prioritised. “We’re also seeing this happen on an institutional level… with [financial] support to create curatorial positions with this as a focus.”

An overview of Xican-a.o.x. Body with, at left, Liz Cohen’s Trabantimino, a witty nod to low-riders based around the infamous East German Trabant

Exhibition Photo: Lazaro Llanes

Ricardo Valverde’s Boulevard Night (1979-91), also featured in Xican a.o.x. Body

Esperanza Valverde and Christopher J. Valverde Collection

A representation deficit

Despite these efforts, Latinx artists in the US are still deeply under-represented. Less than 2.8% of art shown in major museums and arts institutions is made by Latinx artists, according to a 2018 study. Within Xican-a.o.x. Body, Vicario notes that between 70% and 80% of the artists included in the show have little representation in the art market. Despite a definitive push amongst institutions to acquire more work by Latinx artists, Vicario says the vast majority remain largely invisible.

“We are in a moment when there is a lot of activity from places like the Museum of Modern Art [in New York], the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Getty; [they] are lining up for artists who don’t have a lot of material available,” he says. “It’s interesting to sit back and watch what’s happening, because it’s very clear who’s being left out.”

In fact, the organisers of Xican-a.o.x. Body faced some challenges in finding a home for the exhibition. After they received support from the Terra Foundation for American Art, plans to debut the show at the Phoenix Art Museum fell through, Vicario says. The exhibition eventually opened at the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art in Riverside, California, before Vicario landed at Pamm and fought for the exhibition to travel there.

His co-curator Fajardo-Hill says this shows the strong resistance many US institutions face when presenting exhibitions deemed “political” because they centre the experiences of non-white groups. While many museums were not interested in the exhibition, “the ones that were more interested didn’t have the budget, and the ones that could actually do it didn’t want to take it”, she says, noting that she encountered the same resistance when she curated Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985 in 2017. She adds: “Even within Latinx art, there is a hierarchy.”

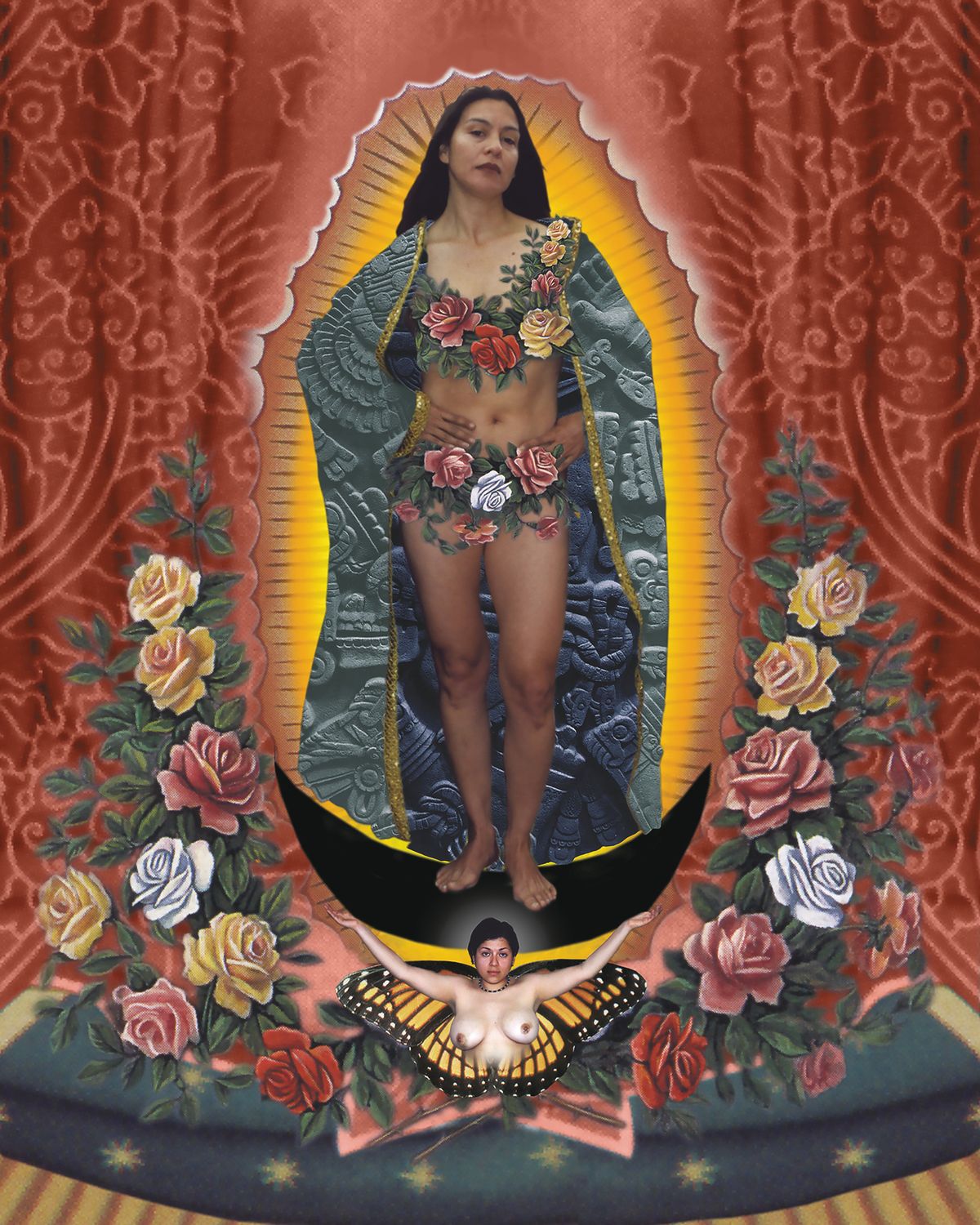

The co-curators of Xican-a.o.x. Body sought to break with that hierarchy with an approach that is both intergenerational and multicultural. The exhibition begins by highlighting artists who were working in the 1960s and creating the framework through which to make sense—both intellectually and aesthetically—of the Spanish-speaking diaspora before terms like Latin, Hispanic and Latinx became widespread. Works like Marcos Raya’s images reflecting on the connections between Latin America, drugs and war by staging photographs of mangled uniformed soldiers; Art collective ASCO’s archives of essays, exhibitions and intellectual happenings centred on the Latin experience from the 1970s and 80s; and Alma López’s Our Lady (1999)—a work that stirred controversy for subverting the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe—provide context for pieces by contemporary artists like rafa esparza, Narsiso Martinez and José Villalobos, who reflect on how Latinx bodies take up space in the US.

After its run at Pamm, Xican-a.o.x. Body is expected to travel elsewhere in the US, though specific plans have not yet been announced. But for Vicario, the exhibition’s position at a prominent museum during the week the whole art world’s attention is focused on Miami already gives it the potential to have a groundbreaking impact.

“The Chicano community may not be as big as these other [Miami] communities that are connected to the Caribbean and to South America, but at Pamm our goal is to be part of the larger conversation around Latinx culture in this country,” he says. “It is beyond my wildest dreams that this show is going to be up during Art Basel, and it will have this exposure and potential for a curator to walk in and say, ‘I need to take this show’.”