The French poet and art critic Wilhelm Apolinary Kostrowicki had a knack for names, starting with his own nom de plume, Guillaume Apollinaire. Born in Rome to Polish parents, he arrived in Paris in 1900 and went on to become the master of ceremonies of the Parisian avant-garde. Apollinaire is remembered for popularising or coining the now-indispensable terms Cubism and Surrealism to describe what his artist buddies were getting up to in Montmartre and Montparnasse. But this month, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York will revisit one of his lesser-known monikers, Orphism, as a way to shed new light on the origins, afterlife and key personalities of abstraction.

Featuring 82 works by 26 artists, Harmony and Dissonance: Orphism in Paris, 1910-30 harkens back to Apollinaire’s separation of figures like Robert Delaunay and Francis Picabia from Pablo Picasso and George Braque, Cubism’s inventors.

Inspired by Paul Cézanne’s geometric shapes and their own Paris encounters with non-European art and objects, Picasso and Braque initially relied on an ochre-and-dung palette and the spatial reinvention of the still-life. Delaunay, Picabia and the show’s other major figure, the Czech-born mystic František Kupka, typically drew their inspiration from colour theory, music and the dynamism of contemporary urban life.

Robert Delaunay's Eiffel Tower (1911) (inscribed 1910) Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Lyrical and emotional

Orphism, as it was originally described by Apollinaire, was largely compressed into a handful of years, but the curators here are using the term “in an elastic sense”, says Vivien Greene, who co-curated the show with Tracey Bashkoff. Works on view reach all the way back to an 1864 book on colour theory by the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, and forward to a 1940s painting by the French artist Albert Gleizes, another early theoretician of Cubism.

The term Orphism, with its implications of a lyrical and emotion-driven approach to art, has fallen out of common usage, Greene says. Even in its own time, it was not widely adopted by its best-known practitioners. Delaunay and his wife, the artist and designer Sonia, had their own term to describe their veering towards colour-driven, dynamic abstraction: Simultanism, invoking the overlapping experiences of the 20th-century city. Kupka, whose de facto feud with Apollinaire meant that he was left out of the poet’s growing short list of Orphists, rejected categories of all kinds, but he was firmly working in an Orphist idiom, Greene stresses.

A highlight of the show will be the public unveiling of two recently treated works by the artists that are part of the Guggenheim’s permanent collection.

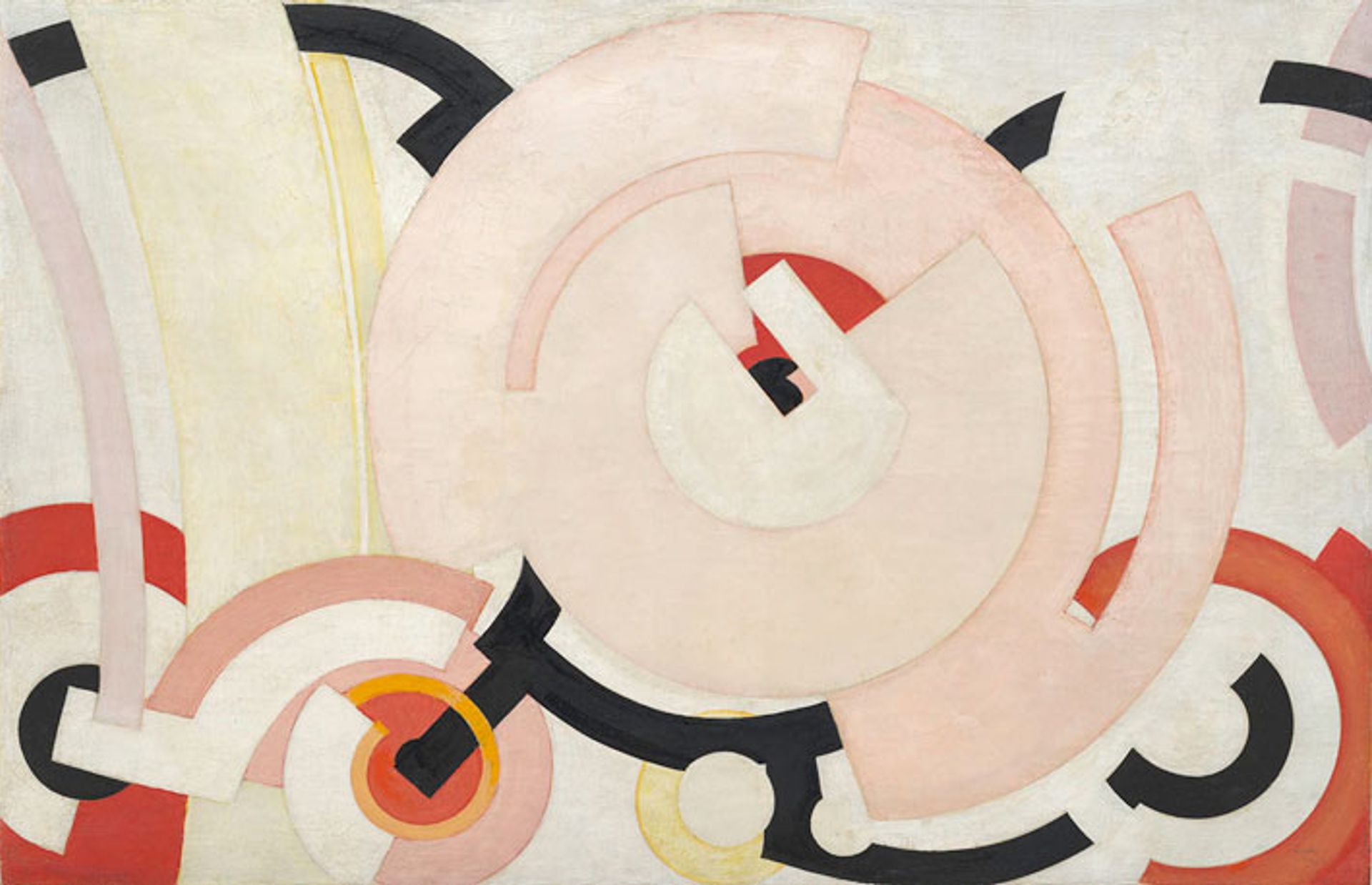

František Kupka's Divertimento I (1935) Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Harbinger of modernity

Robert Delaunay, whose initial artistic experiments involved depictions of a Parisian Gothic church, eventually settled on the Eiffel Tower as a recurring motif, and he helped convert it from a late-19th century relic into an uncanny harbinger of modernity. His early work in the series, inscribed 1910 but now believed to have been completed in 1911, has had “years of accumulated grime removed”, says Julie Barten, the Guggenheim’s senior paintings conservator.

A 1935 Kupka work, Divertimento I, was acquired in 2000, but restorers have waited until now to attempt treatment, Barten says, in order to take advantage of advances such as new nanogel technology to clean off decades of grime. The work came to the Guggenheim from a private collection, she explains, “and we think there were smokers and a fireplace”.

Due to the size constraints of its swirling Frank Lloyd Wright building, the Guggenheim can rarely make the most of its Modernist holdings, reserving its signature gallery ramps for special shows. Harmony and Dissonance will remedy that by combining popular Guggenheim works only occasionally on display, like Gleizes’s On Brooklyn Bridge (1917) with his oil-on-burlap work Painting for Contemplation, Dominant Rose and Green (1942).

Colour-rich and music-mad

The exhibition extends its roster beyond the usual suspects, bringing in Orphist-adjacent works by the likes of the Portuguese painter Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso and the US artist Morgan Russell, whose own colour-rich, music-mad abstract works were examples of what he called Synchromism.

The 1930s and early 40s—decades after Orphism, as most people understand the term—are presented here as a kind of coda, Greene says. She and Bashkoff have added two 1930s works by the Irish painter Mainie Jellett, a protégé of Gleizes’s. Her abstract Painting (1938) is marked by vividly coloured orbs that demonstrate “an adherence” to the movement, Greene says.

Apollinaire died of influenza in 1918, Picabia became a Dadaist, and Robert Delaunay drifted back to figuration. Considering the broader impact of Orphism unfortunately falls outside the scope of the show though, Greene says, adding: “We will need a part II someday.”

• Harmony and Dissonance: Orphism in Paris, 1910-30, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 8 November-9 March 2025