Steve McQueen has a way of seeing through things. Human history, to name one. Cinema history, too. Both are full of blind spots. Take, for example, The Jazz Singer, the 1927 movie starring Al Jolson. As the first motion picture to have synchronised speech and sound, it became an instant classic. Yet, what catapulted it to lasting fame was Jolson’s performance—in blackface.

McQueen could never get past it. Why did that have to be the first talkie? For 20 years he ruminated over a suitable way to address the movie’s casual racism. It needed context. He nailed it by doing something he has never done before in his art. He made it personal. The result was Sunshine State, a two-channel video installation that has been making rounds for a couple of years. Now it’s at Dia Chelsea.

Donna De Salvo, the Dia Foundation’s senior adjunct curator for special projects, is exhibiting the video with two other works: Bounty (2024), a suite of colour photographs depicting single flowers in Granada, where McQueen’s parents were born; and Exodus (1992-97), a video short that McQueen made on the fly, when he spotted two West Indian men gingerly walking tall potted palms through London traffic.

Dark legacies

Sunshine State illuminates a piece of dark matter in McQueen’s own family as well as within himself. The Jazz Singer’s storyline is also Jolson’s: a young man’s ambition to be a pop music idol causes a rift in his observant Jewish family, who push him to follow his father in becoming their synagogue’s cantor. He escapes that destiny by disguising himself in the blackface of a 19th-century minstrel show, a uniquely American form of entertainment that promoted racial stereotypes.

At the time, many regarded Jolson’s success as a triumph of assimilation. But The Jazz Singer also inspired Walt Disney to adopt minstrel show accoutrements—big eyes, exaggerated lips, a servant’s white gloves—in his first animations of Mickey and Minnie Mouse, earning enormous profits.

Sunshine State is commentary as diary, at once biting and poignant. It begins with a close-up view of our burning sun on a double-sided screen beside a more distant, reverse view of the same fiery orb on a second screen. Within New York’s temple to Minimalism, the two look like a cosmic circle and a square hanging above the floor, accompanied by a low electronic hum.

The act of erasure

About ten minutes into the video’s 40-minute length, scenes from The Jazz Singer appear on the screens but out of sync, moving forward and backward in positive and negative exposures, allowing McQueen to digitally white or black out Jolson’s face. As the artist told De Salvo in a public conversation at Dia, “I wanted Jolson to erase himself.”

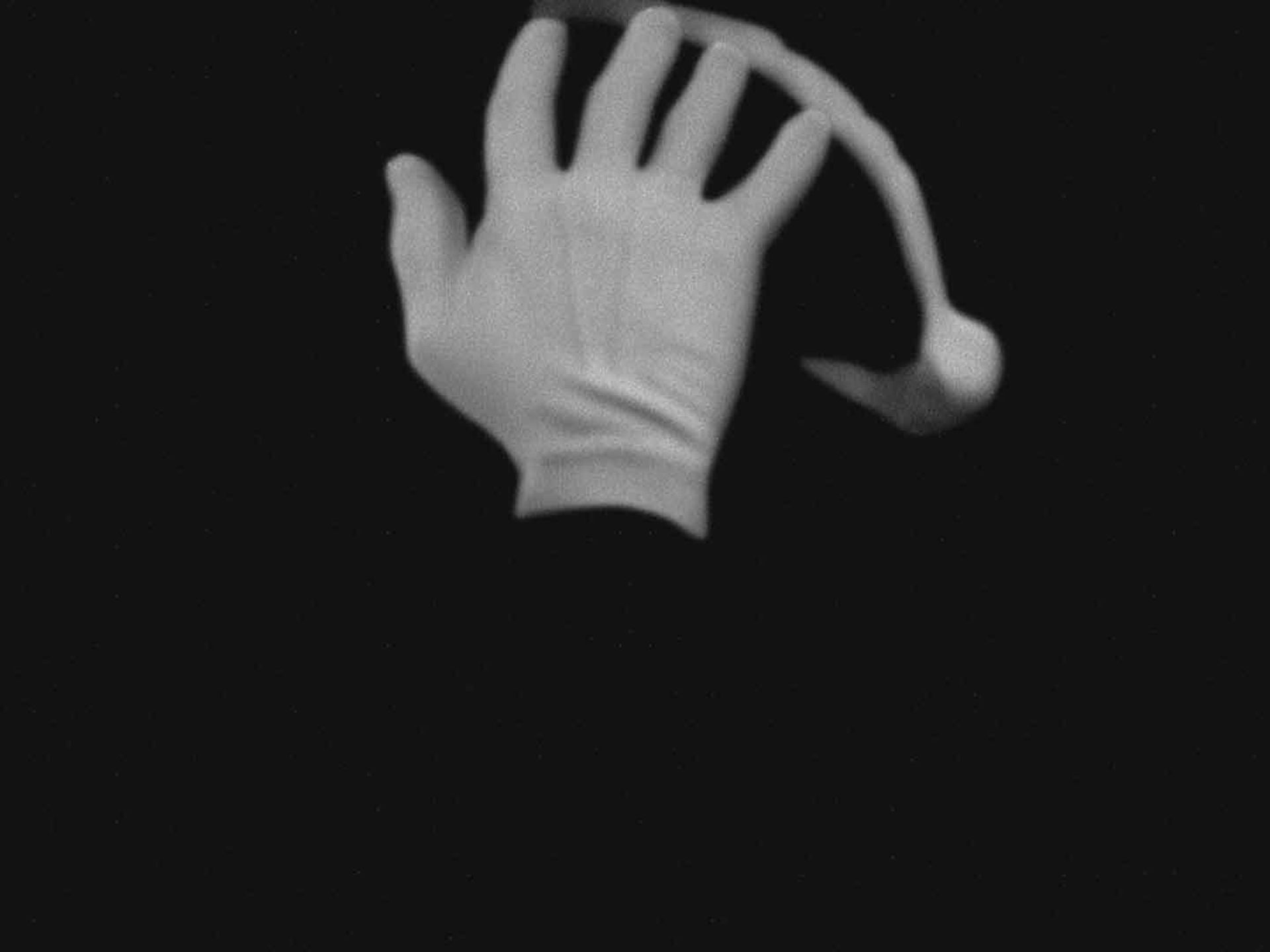

The actor does not wear white gloves in The Jazz Singer. In McQueen’s video, he does. The artist also replaced the film’s soundtrack with his own voice. It tells and then retells, in four elided fragments, a story of racially motivated violence that involved his father as a migrant orange picker in Florida, a.k.a. the Sunshine State.

A scene from Sunshine State (2022) altering Al Jolson’s image in The Jazz Singer to show him wearing white gloves

© Steve McQueen.Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery. A Commission for International Film Festival Rotterdam 2022. Footage from The Jazz Singer courtesy Warner Bros Pictures

“I was shocked by that story,” McQueen told De Salvo. Not because it was uncommon, but because his father waited until he was on his deathbed to recount an incident that had shaped his entire life. “It’s about the fragility of life as a Black man,” McQueen observed. In his voiceover’s most moving passage, he says: “I thought he was holding me back, but I didn’t realise ’til then that when he told me that story, he was holding me tight.”

Sweet with pain

McQueen is expert at luring audiences into power dynamics that are very unpleasant—Twelve Years a Slave, for example. “Sometimes,” he remarked at Dia, “the most horrible things happen in beautiful places.” That principle applies to the flower pictures in Bounty. They look like generic iPhone photos. What they represent, however, is trauma—and resilience. Each flower grows on sites in Grenada where invading Europeans massacred the island’s citizens again and again, over centuries. Yet the seeds, the soil’s secrets, keep growing. “I think of them as flesh wounds,” McQueen said of the flowers, describing their scent as “sickly sweet, sweet, sweet with pain”.

Installation view of Steve McQueen, Bounty (2024)

Photo: Don Stahl. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation

His exhibition is not so sweet, but it navigates another sticky territory, which is family, with all the love and fury any journey to its core demands.

- Steve McQueen is at Dia Chelsea until 13 July 2026; Bass, a concurrent commission, is at Dia Beacon until April 2025