This year’s Art Toronto fair is nothing if not a metaphor for the contemporary Canadian experience.

Staged in a convention centre on the banks of Lake Ontario in a place that was once a traditional trading grounds for local First Nations, Canada’s largest art fair opening to the public today (until 27 October) is part cultural emporium, part diorama of a national aesthetic. It is a gathering of the gallery tribes from coast to coast, a destination for collectors and a chance for artists and dealers from disparate regions to catch up on the latest trends.

If it were a Leonard Cohen song, it would be a hybrid of Hallelujah and One of Us Cannot Be Wrong. If it were a quotation from the author Robertson Davies, it would be this one: “I see Canada as a land torn between a very northern rather mystical, extraordinary spirit which it fears and its desire to present itself to the world as a Scotch banker.”

But as one ascends an escalator (passing, during Thursday’s preview, an unfolding Indian wedding in an adjacent lobby) and enters into the section of the Metro Toronto Convention Centre that houses the fair, any lingering sense of Presbyterianism is overwhelmed by sheer scale, mass and diversity—much like Canada itself. With its mix of public, private, non-profit and commercial galleries, blue-chip and emerging artists, Art Toronto is a moveable feast of Canadiana spread across 200,000 sq. ft and more than 100 stands.

Sami Tsang installation at Art Toronto, presented by Cooper Cole Photo courtesy Art Toronto

Visitors are greeted at the top of the escalators by an installation by the Toronto-based Chinese artist Sami Tsang (presented by the local gallery Cooper Cole)—a phantasmagorical piece that resembles a giant monster baby emerging from traditional pottery—and an accompanying large-scale painting depicting the same.

Serendipitously or by design, its neighbours are the stands of the National Gallery of Canada and the McMichael Canadian Art Collection—whose grounds in nearby Kleinburg, Ontario literally contain the bones of the Group of Seven, six of whom are buried there. They are buffered by the non-profit Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery and an installation of textile and video work about ancestral memory by Michaëlle Sergile, a Montreal-based Haitian artist, presented by Galerie Hugues Charbonneau.

Around the corner is the stand of the Vancouver-based Portfolio Collective group, which includes members of the Young Romantics group—painters, Angela Grossman, Attila Richard Lukacs and Graham Gillmore, as well as Douglas Coupland and this year’s Audain Prize winner Rebecca Belmore. Profits from the sales of their work will go to support the Portfolio Prize for young emerging artists.

A VIP reception at Art Toronto benefitted the McMichael Canadian Art Collection Photo courtesy Art Toronto

The emerging American artist Lamar Robillard is enjoying his first experience at the fair on the stand of Black Artists’ Networks in Dialogue (or Band Gallery). The 33-year-old mixed media artist is hoping to sell two works inspired by Afrofuturism and ancestral ceremony. If Sun Ra Gave Me The Keys To His Spaceship, made of repurposed wicker and cowrie shells, sits next to a piece called Holding Space (2020), which features incense sticks emerging from a bust-like ceramic vessel. The gallery is hoping sales from the fair will help fund its new space in Parkdale, which is being designed by Diamond Schmitt Architects. Next-door is the stand of Vancouver’s Ceremonial Art, one of the few Indigenous-led galleries here dealing in contemporary idioms.

In keeping with the theme of the fair’s 25th anniversary exhibition, curated by Art Toronto director Mia Nielsen and titled Re: connecting—which rejects the current dominance of digital and artificial intelligence imagery in favour of a more tactile experience—there is a craft-informed three-dimensionality to many of the works at the fair.

The New York-based Claire Oliver Gallery has brought works by the Bahamian Torontonian textile artist Gio Swaby to the fair for the first time. One of her new works at the air made of muslin, cotton and thread has already been acquired by the National Gallery of Canada (whose other acquisitions include a work from Audain Prize-winner Dana Claxton’s photo series Headdress.)

The McMichael Canadian Art Collection acquired Aanzinaago (Caught in a Transformation) 01 (2024), by Native Art Department International, from Patel Brown's stand at Art Toronto Courtesy the artists and Patel Brown

During a reception on Thursday night to benefit the McMichael Gallery, the room was abuzz with well-heeled collectors exchanging information about the next big thing. They eagerly awaited announcements by the gallery’s executive director and chief curator, Sarah Milroy, about its acquisitions from the fair. They included the 2024 work Aanzinaago (Caught in a Transformation) 01 by the Native Art Department International, acquired from the stand of the Toronto- and Montreal-based gallery Patel Brown.

Highlights of the fair’s Focus exhibition, organised by the Métis curator Rhéanne Chartrand around the theme of the home, include works by the Afghan Canadian artist Shaheer Zazai. In a clever interplay between the imagined and the actual, he employed mathematical formulae to create a digital design for a traditional Afghan carpet then gave it to artisans in Afghanistan, who created a real rug. Both the rug and the digital design are displayed.

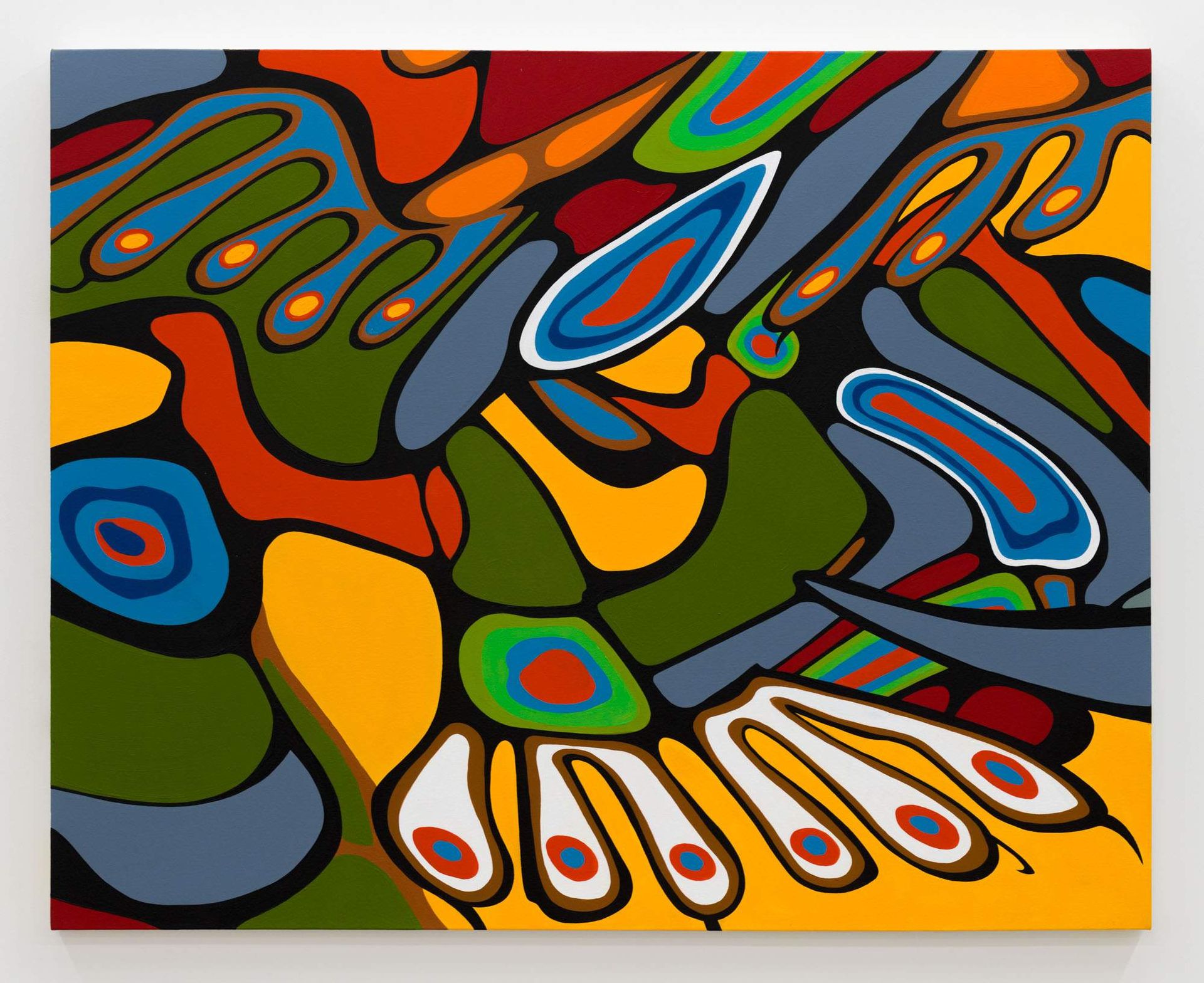

A painting by Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun on the Arsenal Contemporary Art stand at Art Toronto Courtesy Art Toronto

Across the room, a new work by the Vancouver-based artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun depicts damage to unceded territory from recent forest fires. Nearby, the Edmontonian artist Braxton Garneau offers compelling, three-dimensional figurative works made of asphalt (a material representing his grandparents’ journey from Trinidad to Northern Alberta) with details of cloth, raffia and sugarcane pulp made from acrylic and asphalt.

A large installation that looks like a giant plastic tent or hot air balloon, created by Studio Rat and presented by Arsenal Contemporary Art, functions as a participatory device and gathering place.

An installation by Studio Rat, presented by Arsenal Contemporary Art, at Art Toronto Courtesy Art Toronto

Another large installation—The Confessional (2024) by the Guadeloupian, Montreal-based artist Eddy Firmin, presented by Art Mûr—steals the show. His re-creation of an actual confessional chamber offers visitors the opportunity to share stories of their experiences of racism. Their testimonies are then integrated into the installation and can be listened to by visitors seated on the bench outside. Visitors are also invited to drop off racist or xenophobic objects from their own collections on the shelves of the structure’s back wall.

Firmin’s goal, according to an artist’s statement, is “to create other possible outlets for the racist heritage we all possess but don’t know what to do with or no longer wish to keep”. He asks participants: how can we transform such histories without forgetting or denying them, and what can we do with these unwanted heritages?

Firmin’s Confessional offers a potentially cathartic outlet for complicated legacies and important questions for both Canada and its national arts scene.

Visitors at Art Toronto examine Eddy Firmin's The Confessional (2024), presented by Art Mûr Courtesy Art Toronto

- Art Toronto, until 27 October, Metro Toronto Convention Centre North Building, Toronto