For nearly five decades, Sophie Calle has been combining photographs, texts, objects and video to explore the complex nature of human relationships. Frequently using sleuth-like tactics, she mines interpersonal dynamics both within her own life as well as the lives of strangers, with a particular focus on ideas and experiences around love, intimacy, trust and power.

In 2007, Calle represented France at the Venice Biennale with Take Care of Yourself, a work in which she asked 107 women to interpret a letter she had received from a lover breaking up with her. Last year, her exhibition, À toi de faire, ma mignonne, took over the entire Musée Picasso in Paris, marking the 50th anniversary of Pablo Picasso’s death with a characteristically extreme meditation on Calle’s own demise, including a commissioned obituary, the inventoried contents of her house, and a specially selected coffin.

I refused the Musée Picasso show for two years because I thought Picasso was too overwhelming

Her latest exhibition, Overshare, which opened at the Walker Art in Center in Minneapolis last month, is the first exhibition in North America to explore the full range of her practice, including major bodies of work as well as lesser-known pieces. Earlier this year it was also announced that she was one of the five recipients—along with fellow artist Doris Salcedo—of the Japanese Art Association’s prestigious 2024 Praemium Imperiale prize.

The Art Newspaper: Overshare is an intriguing title for your Walker Art Center show. Your work is often described as intimate or even voyeuristic, but arguably it also conceals as much as it reveals. The critic and curator Robert Storr once described it as giving “the structure of the secret, but not the secret itself”. What are your thoughts on oversharing?

Sophie Calle: People think they know my life, in fact they know nothing because I share a great deal about one moment, one situation, but at the same time, I don’t say anything about my life. I don’t have Facebook, I don’t have Instagram, and I share much less than all those people who have blogs or who are on social media. I speak about three men, because they were three interesting break-ups. But I don’t speak about my friends, I don’t speak about the man I’ve lived with for 20 years. I don’t speak about any of this. In the end, I don’t think I share that much.

Nonetheless your work offers access into parts of people’s lives—both yours and others—that can feel both uncomfortably private as well as being utterly compelling and irresistible.

But at the same time, I say nothing. We follow this man in Venice [in the work Suite Vénitienne (1980)], but we don’t know who he is. We just see what’s visible from the outside. We see the people’s things in The Hotel [series (1981)], but we don’t know who they are. So it’s overshare and at the same time, hide everything!

Sophie Calle’s mixed-media work Mother-Father (2018), from the Walker Art Center show. Death is an abiding theme of the artist, and photographs of gravestones are a motif that frequently appear in her work

© 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris; courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery

The idea of play is also very strong, with you taking both the role of a player, but also the one who lays down the rules of the game. You choose situations, and then set them in motion, with very specific instructions that you stick to while letting things unfold. This tension between control and lack of control seems crucial.

Yes, because once you have the rules of the game, then you can go inside and let yourself go, because there is a structure that’s already designed. I am a control freak but I also like to play with what comes by. For me it’s the same paradox as in Overshare.

How do you decide the rules of the game?

Sometimes the rule of the game designs the whole project, sometimes it’s a very strict invitation. For example, I refused the Musée Picasso show for two years because I thought that Picasso was too overwhelming. It was impossible, I could not go side-to-side with Picasso. But then I was invited by [the museum’s former director] Laurent Le Bon to visit the museum during Covid, and at that time, I would have gone anywhere to get out. So I went and I was surprised to see all the paintings of Picasso wrapped up and hidden. Then I thought OK, this I can do. I can go next to a ghost, I can go next to a Picasso who’s there but who you don’t see. And that was what opened it up for me: suddenly I could deal with Picasso by using his absence. I started with the ghost of Picasso, then I searched for things I could play with. The rule of the game came from this sudden opening of his absence.

Unexpected circumstances or encounters also set works in motion, as in the chance meeting with a man at an art opening that triggered Suite Vénitienne (1980), with you following him to Venice and the story unfolding almost like a chain reaction.

Absolutely. I was already following strangers and I wanted to reverse the process, so I did the work with the detective to be followed myself. When I did Take Care of Yourself (2007), it was because I received that [break-up] letter and the shock of reading that phrase from a man who tells you “to take care of yourself” when he’s going. So sometimes it’s just a phrase, or it can be a chance encounter. My project with blind people [The Blind (1986)] is because I crossed the street and I heard a blind man saying to another, “I saw a very beautiful movie yesterday,” and suddenly the paradox of the phrase just struck me.

Overshare is divided up into four sections: The Spy, The Protagonist, The End and The Beginning, which span your career from the late 1970s up to a few years ago. Of course, these sections all overlap, and running through all of them is your very particular response to human relationships, needs and desires.

They are always about something missing, that’s the link that I can find all through the work. They are about a man that goes, a mother that dies, a man that doesn’t see, the painting that has been stolen, a detective following a silhouette, not a real character, or watching people sleeping without knowing anything really about them, just the surface of their sleep. It’s always about something that’s not there.

Why do you think this is the case?

If I am happy with a man, I don’t want to write about him or make a work about him. I want to live with him, not to watch him from a distance. When I make a project, it is often because something is disappearing, is going away, slipping through my fingers. When I filmed my mother dying, it was a way to be with her, night and day, to keep her around. And now, because of this project about her death, Pas pu saisir la mort (impossible to catch death, 2007), we are talking about her and she’s still there every day with me. With No Sex Last Night (1992)—a break-up again—even though it was painful, through that movie, we stayed together… So making such projects can be a way not to let things go and to reverse situations too difficult to deal with.

Death is a dominant theme throughout your work: whether stranger’s gravestones, the deaths of your parents, a musical memorial to your cat, and even your own death, featured in the Musée Picasso exhibition. But death is treated with humour, you are never morbid or sentimental.

Because if you are very emotional about the project, you don’t leave any space for anyone else, you decide for them. The only way to describe those difficult moments is to be dry, to take a distance, and to leave space for the spectators.

People often associate you with pushing scenarios to the limit, going through a found address book, scrutinising strangers, filming your mother on her deathbed. Within the rules that you set, do have any parameters?

It is the project that gives the limitation. My mother was very eccentric and she wanted to be always at the centre. My father was a Protestant, very discreet. He wanted to be hidden. When I filmed for hours and hours my mother dying, I knew she would love it. If I had done this with my father, it would have been an aggression, in a way. So sometimes the limit is not even the idea, but who it is about. And also, the limit can be that sometimes you ask yourself if it is worth doing. Each idea has its own limit. Is it interesting, poetic enough? Or is it just provocative? Even then, it depends. Sometimes I like a little provocation because in the end it works.

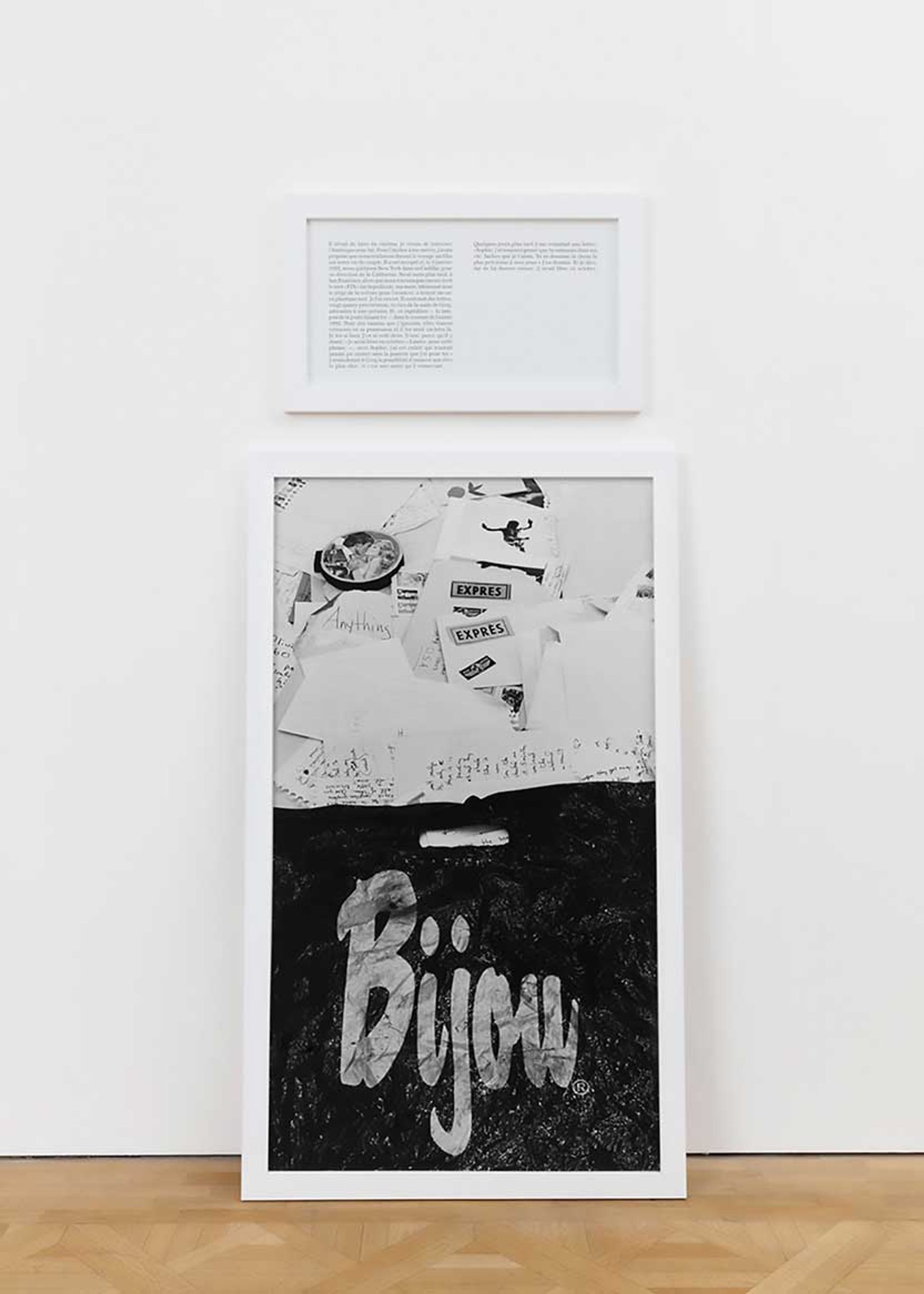

Calle’s photo-and-text work The Breakup (1992) is part of a series examining the collapse of a relationship

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris; courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery

You have just been awarded the 2024 Praemium Imperiale Award, rather surprisingly in the category of painting—not a medium you are usually associated with. What do you feel about winning this prestigious prize?

Strange indeed to become suddenly a painter. But since they don’t have a category for photography, they have to adapt. Maybe I should also adapt to the prize myself and start painting? And about my feelings? Mainly happy when I see the list of the artists who [also] got it.

Biography

Born: 1953 Paris

Lives and works: Paris

Key shows: 1986 De Appel, Amsterdam; 1990 Institute of Contemporary Art Boston; 1991 Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; 1998 Tate, London; 1999 Camden Art Centre, London; 2003 Centre Pompidou, Paris; 2007 Venice Biennale; 2009 Whitechapel Gallery, London; 2010 Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek; 2012 Museo de Arte Moderno, Medellin, Colombia; 2019 Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo; 2022: Musée d’Orsay, Paris; 2023 Musée Picasso, Paris

Represented by: Perrotin, Paula Cooper Gallery and Fraenkel Gallery

• Sophie Calle: Overshare, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, until 26 January 2025