Touring post-war Germany in 1950, the philosopher Hannah Arendt was struck by an apparent inability of people to face the reality of their destroyed world: “Amid the ruins,” she wrote, “Germans mail each other picture postcards still showing cathedrals and market places, the public buildings that no longer exist.”

Architecturally, Germany’s attempts to face its cultural losses and reconcile the horrific recent past with an unknown future resulted in a number of tendencies. There were the Modernists who desired a complete break with a history that had culminated in anti-Modern Hitlerism and instead urged a tabula rasa raising of a new material world. Then there were traditionalists who saw the Third Reich as itself a product of rootless Modernity and yearned to reinstate a comforting, prelapsarian world.

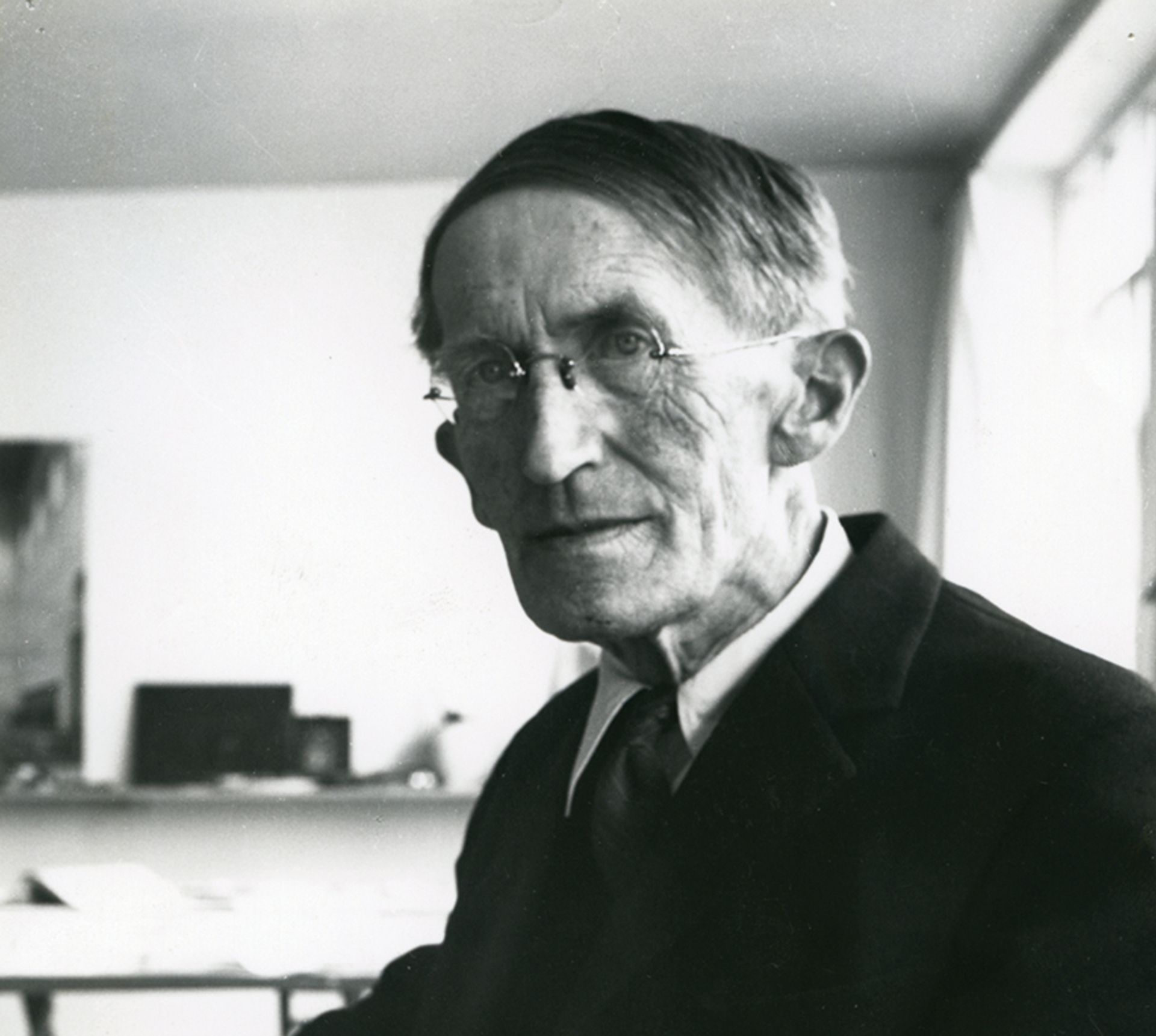

For Hans Döllgast, who died 50 years ago this year, pragmatism rather than ideology always guided his building restoration projects Architekturmuseum der TUM

Both approaches were deployed at different times and in different German cities. Both ran the risk of erasing memories and the physical record of the reality of the Nazi period. And without memories or evidence, a reckoning with that past becomes impossible.

Creative reconstruction

The Bavarian architect Hans Döllgast (1891-1974), however, pioneered a minority third way: critical or creative reconstruction, which takes a layered, collaged approach to reconstruction. It advocated using the material of the past for its own disposal, adapting damaged places in ways that incorporated the scars of conflict, balancing preservation with renewal, memory with forgetting—even if these aims were often not articulated. His was a far from purist, archaeological conservationist approach in the tradition of John Ruskin or William Morris’s Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

Döllgast’s creative repairs to Munich’s monuments, where 60% of the old city had been destroyed by Allied bombing, were prime examples of good practice. But by the time he died in 1974, his creative reconstruction approach had largely been abandoned. In Munich, the trads had won out, reconstructing much of the old city in facsimile. Other German cities took a Modernist line. But in the past decade, a “friends” organisation began to arrange tours and exhibitions of his work in Munich. And this summer saw a conference at the Technical University of Munich School of Engineering and Design marking the 50th anniversary of his death.

In our century, the question of appropriate post-conflict reconstruction—and Döllgast’s lessons—could not be more relevant. Urban warfare has savaged cities from Mosul, to Homs, Khan Yunis to Kharkiv. Across Europe, far-right nativists are funding pastiche reconstructions of not just ruined but entirely long-vanished castles, palaces and churches, creating mythic nationalist pasts as a means to culturally “other” those deemed not to belong. Long-respected conservation standards are being abandoned. Budapest’s Unesco World Heritage Site is only one place among many whose material authenticity is at risk from these fantasies.

A ‘soft’ Modernist

Döllgast began his career working with Peter Behrens in the latter’s Expressionist phase. He was a “soft” Modernist never doctrinaire or hostile to history and appreciative of other currents—Scandinavia’s interwar Classicism, for example. He later worked on a number of church projects and began teaching at Munich’s Technical University.

Never clubbable, Döllgast preferred to work at the margins, although his apolitical, quiet-life moderation was craven in hindsight, allowing his career to continue under the Nazi regime—he was involved in town planning work for Nazi-colonised Poland. While no dissident, he was deemed by the Allies “uncompromised” by Nazism.

Döllgast’s magnum opus is the reconstruction of the Alte Pinakothek, a neo-Renaissance palazzo built from 1826 to 1836 to house the Bavarian royal art collection. The top-lit spaces, some of which were proportioned to match the paintings displayed, were pioneering. One third of the building was destroyed by wartime bombing and the remainder left a burned-out shell. Amid the fierce reconstruction debates, Döllgast again avoided an ideological position, arguing pragmatically for his scheme on cost efficiency grounds at a time when many wanted the ruins of the museum (disparaged as the “old cupboard”) to be levelled. From 1946 onwards, he pushed for a collaged reconstruction for the Alte Pinakothek that used patched blockwork and blitz rubble to infill the ruins and which simplified detailing that blended rather than aggressively juxtaposed new and old, while still maintaining a visual distinction between the surviving historical fabric and his gentle Modernist interventions.

He had already proved the worth of his approach at a smaller scale elsewhere in Munich, including delicate steel and timber interventions in the damaged pavilions of the city’s historic cemeteries.

After six years of campaigning, he got his way and the Alte Pinakothek finally reopened in 1957. His interventions included radical replanning that moved the entrance and installed an immense scala regia in place of a former colonnade.

The Cambridge University academic Maximilian Sternberg, who spoke at the Munich conference, and is writing a book on Döllgast, notes that he was critical of the idea of taking aesthetic pleasure in ruins—what we might today call “ruin porn”—describing it as “pitiless”. He was instead interested in the quality of the originals.

In some respects, Döllgast’s “creative reconstruction” has an affinity with that of Carlo Scarpa, who was remodelling Verona’s Castelvecchio Museum at a similar date. But his pragmatism rather than zealotry meant that, despite some interest from the architects James Stirling and the Smithsons, he remains far less-known internationally. More recently, David Chipperfield has been among Döllgast’s most prominent champions. The Alte Pinakothek directly informed Chipperfield’s reconstruction of the Neues Museum in Berlin.

Even so, Munich’s conservatives have lobbied repeatedly over decades to remove Döllgast’s innovative façades at the Alte Pinakothek and reinstate 19th-century facsimiles. Amid a rise of nativism and nationalism across Europe—including in architectural and heritage—Döllgast’s sensitive third-way innovations offer a more honest way forward.