Surrealism winds its marvellous way across borders, genders and art forms

One hundred years ago this October, André Breton wrote his first Surrealist Manifesto, widely recognised as the starting point of the movement. Rejecting rationalism as “hostile to any intellectual or moral advancement”, the French poet extolled the superiority of the subconscious mind and presented Surrealism’s lack of logical limitations as “the new mode of pure expression”.

To celebrate the anniversary of Breton’s manifesto, the Centre Pompidou organised a travelling loan of 30 Surrealist works from its permanent collection, inviting venues from Brussels to Philadelphia to exhibit them alongside others. Now this world tour, simply titled Surrealism, has come full circle to the Pompidou until 13 January 2025, featuring 550 works from every conceivable discipline.

Visitors enter the exhibition through the gaping jaws of the Leviathan, “a re-creation of the door to the famous Cabaret de l’Enfer”, says the show's co-curator Marie Sarré, referring to the Surrealist hangout whose monstrous façade was once visible from Breton’s Montmartre studio. Past the dramatic entryway, she and her co-curator Didier Ottinger turn visitors’ attention to the movement’s literary origins in Paris, placing Breton’s original manuscript—on loan from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France—at the physical and conceptual heart of the show.

“It was very important to present the manuscript as the beginning of the project,” Sarré says. “It defines and outlines the main principles of Surrealism: the marvellous dreams and the imagination; how we can change lives and transform the world.”

The scenography unfurls as a spiralling labyrinth, echoing Marcel Duchamp’s design for the 1947 International Exhibition of Surrealism in Paris while also capturing the movement’s fascination with funhouses and public spectacle. Although it boasts important works by Salvador Dalí, Giorgio de Chirico, Man Ray and many others, the exhibition reaches beyond Surrealism’s traditional icons. Lesser-known pieces offer pleasant surprises, such as Dorothea Tanning’s Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202 (1970-73), an artificial room in which naked ghosts burst through the walls. Tatsuo Ikeda’s ink drawing from around 1956, Family, from Chronicle of Birds and Beasts, traces Surrealism to Japan, while the artist known as Mayo’s 1937 mixed-media piece, Dessin Cruel, locates the movement in Egypt.

Spanning such topics as clairvoyance, antifascism, alchemy and lust, the works here are organised by literary themes. The whimsically illogical are filed under Alice, in honour of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Trajectory of the Dreams elucidates Breton’s fascination with Freudian psychoanalysis.

“It’s not just an artistic movement but a current of thought that was intellectual, poetic, literary, artistic and political,” Sarré says. The section Hymns to the Night dives into the uncanny worlds of Brassaï’s nocturnal photographs and the Spanish film-maker Luis Buñuel’s short Un Chien Andalou (1929), which was co-written with Dalí and features a famous scene in which a woman’s eye is sliced open in close-up.

Historians say that Surrealism lasted from 1924 until the writer Jean Schuster’s official dissolution of the group in 1969. Yet after viewing the show at the Pompidou, one may start to see its spirit everywhere, from the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch and the aquariums of Pierre Huyghe to the ceramic vessels of Julia Isídrez. Even within the official timeline, there are certainly more Surrealists yet to find their way into the spotlight. “During those 40-odd years”, according to Sarré, “we saw a lot of personalities challenging rationalism and proposing a new relationship with the world”.

Bruma D1 (2018) by Olga de Amaral is part of her retrospective at the Fondation Cartier from 12 October. The Colombian artist explored many techniques, including weaving and the striking use of gold leaf

© Olga de Amaral, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

A pioneering textile artist finally receives her due

The Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain will stage the first major European survey of Olga de Amaral (12 October-16 March 2025), the Colombian artist whose textile-based practice blurs distinctions between tapestry, painting, installation and sculpture. Presenting around 90 works, the exhibition will trace the evolution of Amaral’s career from its origins in the Fibre Art movement of the 1960s and 70s, highlighting the myriad influences that have impacted her work.

Born in 1932 in Bogotá, Amaral trained as an architect at the Colegio Mayor de Cundinamarca before travelling to the US to attend the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where she studied weaving. Amaral’s work is distinguished by her wide-ranging explorations of techniques and materials, including her signature use of gold leaf, inspired by the Japanese kintsugi tradition of repairing cracks and fissures with gold powder. The exhibition will incorporate the distinct bodies of work Amaral developed over six decades of experimentation, including her Estelas series of gilded cotton weaves that project the weight of slabs of gold, and her Brumas, or mists, comprising individual fibres suspended together as a single, transparent mass and painted with geometric patterns that unfold in three dimensions.

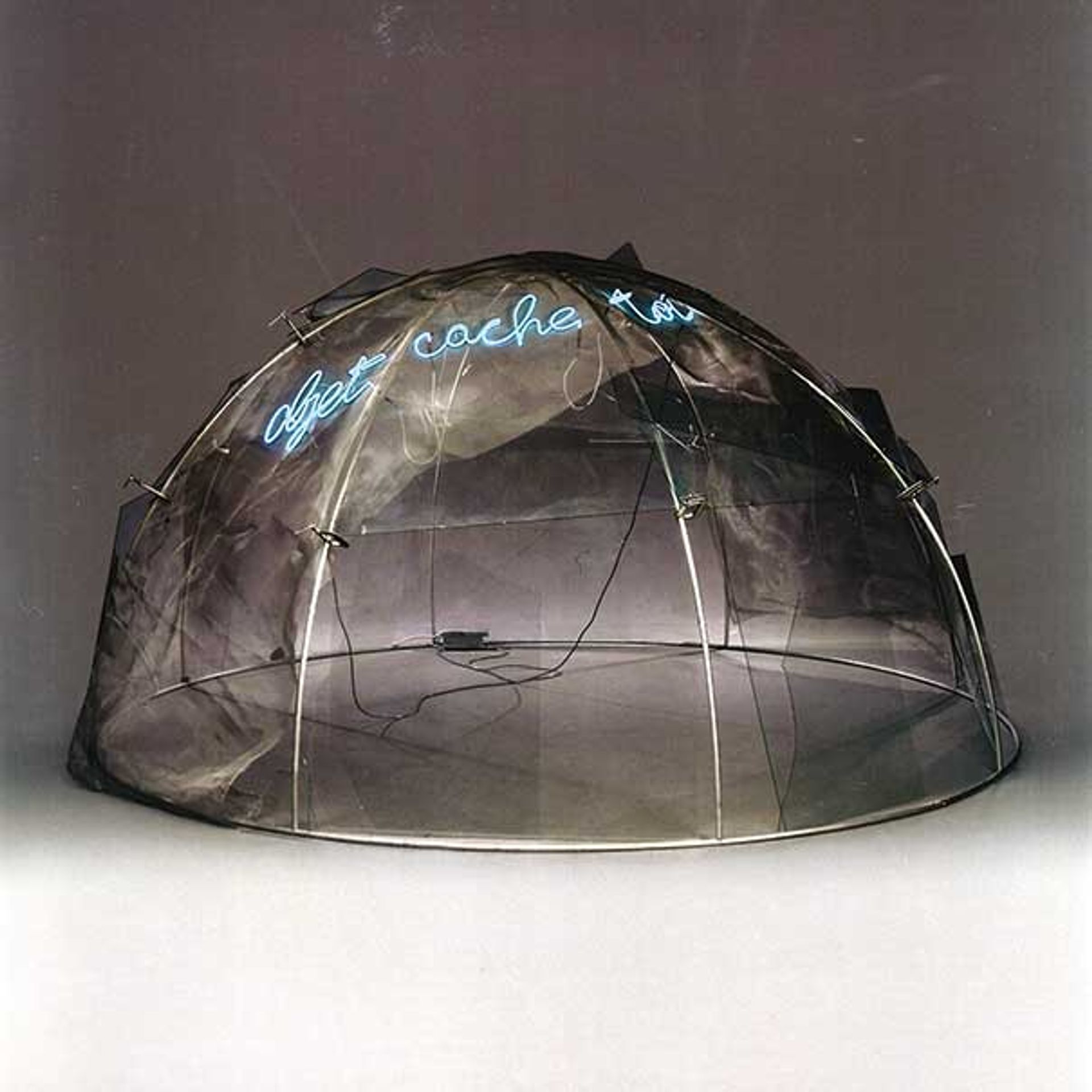

Mario Merz's Igloo Objet cache-toi (1977) in Arte Povera at the Bourse de Commerce

© Adagp, Paris, 2024; photo: Christie’s images LTD

Spotlighting the rebel spirit of Arte Povera

In 1967, the critic and curator Germano Celant coined the term Arte Povera, or “poor art”, to describe an experimental Italian movement rooted in humble materials and ephemeral performances. “Jannis Kounellis recuperates artistic gesture in feeding bird food to birds,” the critic wrote, and “the rest of the world can go to hell”. Kounellis joins Mario and Marisa Merz, Giuseppe Penone and Michelangelo Pistoletto among the 13 artists to headline Arte Povera (9 October-20 January 2025) at the Pinault Collection’s Bourse de Commerce site.

Curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the show is rooted in imagery of Penone’s living tree sculptures alongside Mario Merz’s igloos of mesh and aluminium and Pier Paolo Calzolari’s sculptural refrigeration tubes. The inclusion of contemporary artists such as David Hammons and Theaster Gates highlights the endurance of the movement’s spirit into the present day. To Celant, Arte Povera was not a style but an ideology of rebellion, rejecting “the call to produce fine commercial merchandise” in favour of the banal textures of everyday life.

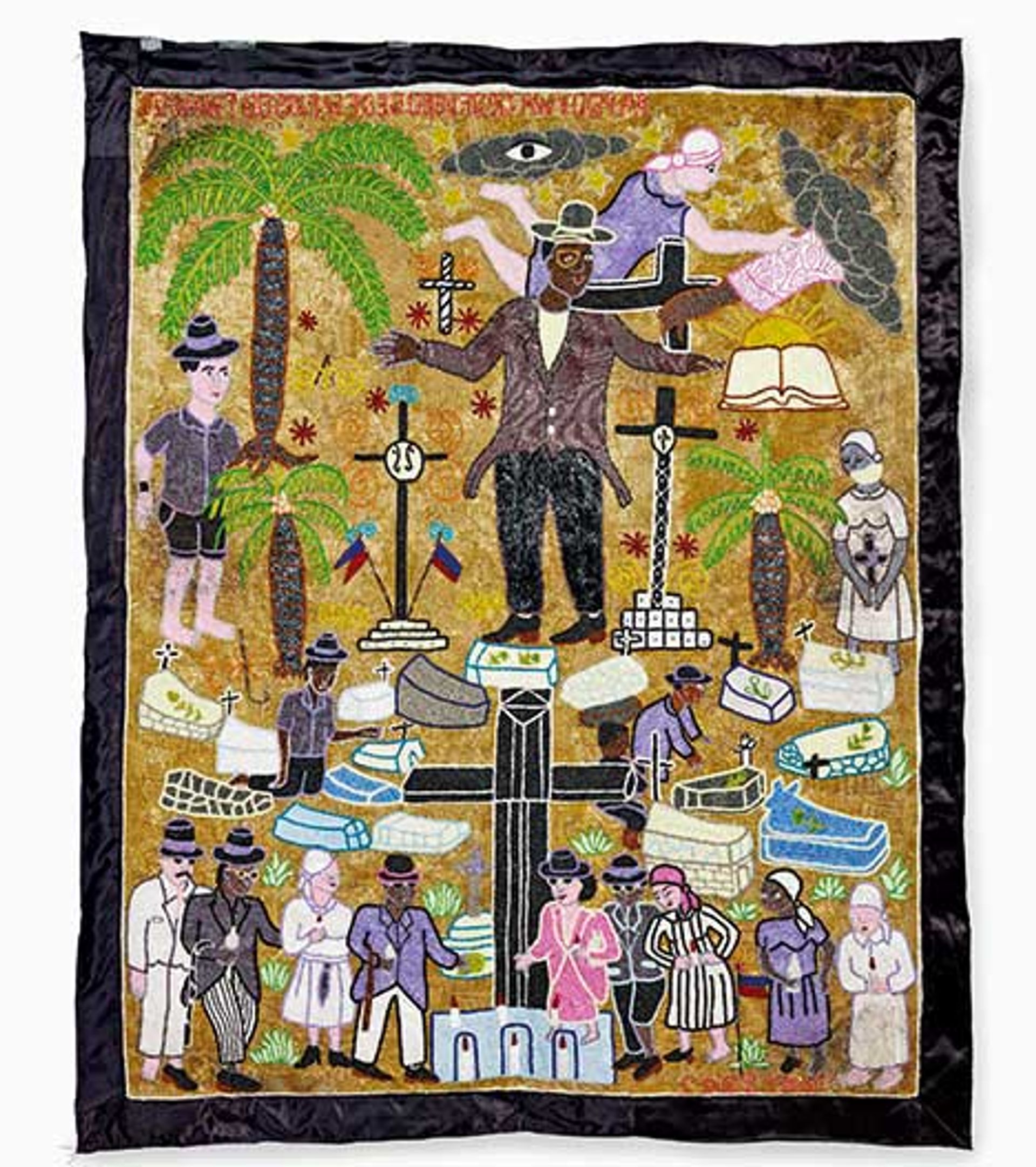

Myrlande Constant's Bannière Bawon (2005) is a textile depicting voodoo folklore in Haiti

© Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac; Photo: Claude Germain

The undead march from myth to museum

Located in a radically designed building by the architect Jean Nouvel, the Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac is a steward of non-European art. Its latest exhibition, Zombies: Death is not the end? (until 16 February 2025), begins by locating the zombie’s origin in Haitian voodoo, presenting the fetish dolls of the island’s Bizango secret societies and various other evil charms. From there, the show traces the zombie’s complex origins to the African, Indigenous American and European faiths that merged under the forces of colonisation and the Transatlantic slave trade to form the syncretic voodoo faith. Here, works include 19th-century West African sculpture and Catholic crucifixes often found in voodoo temples and offerings. The third phase of the exhibition charts the export of the zombie myth from Haiti into international folklore, contemporary art and popular culture, via works ranging from the sculptor Gabriel Bien-Aimé’s examples of bosmétal, a type of metalwork specific to Haiti, and Myrlande Constant’s painterly textiles, all the way to Michael Jackson’s Thriller and the hit US television series The Walking Dead.

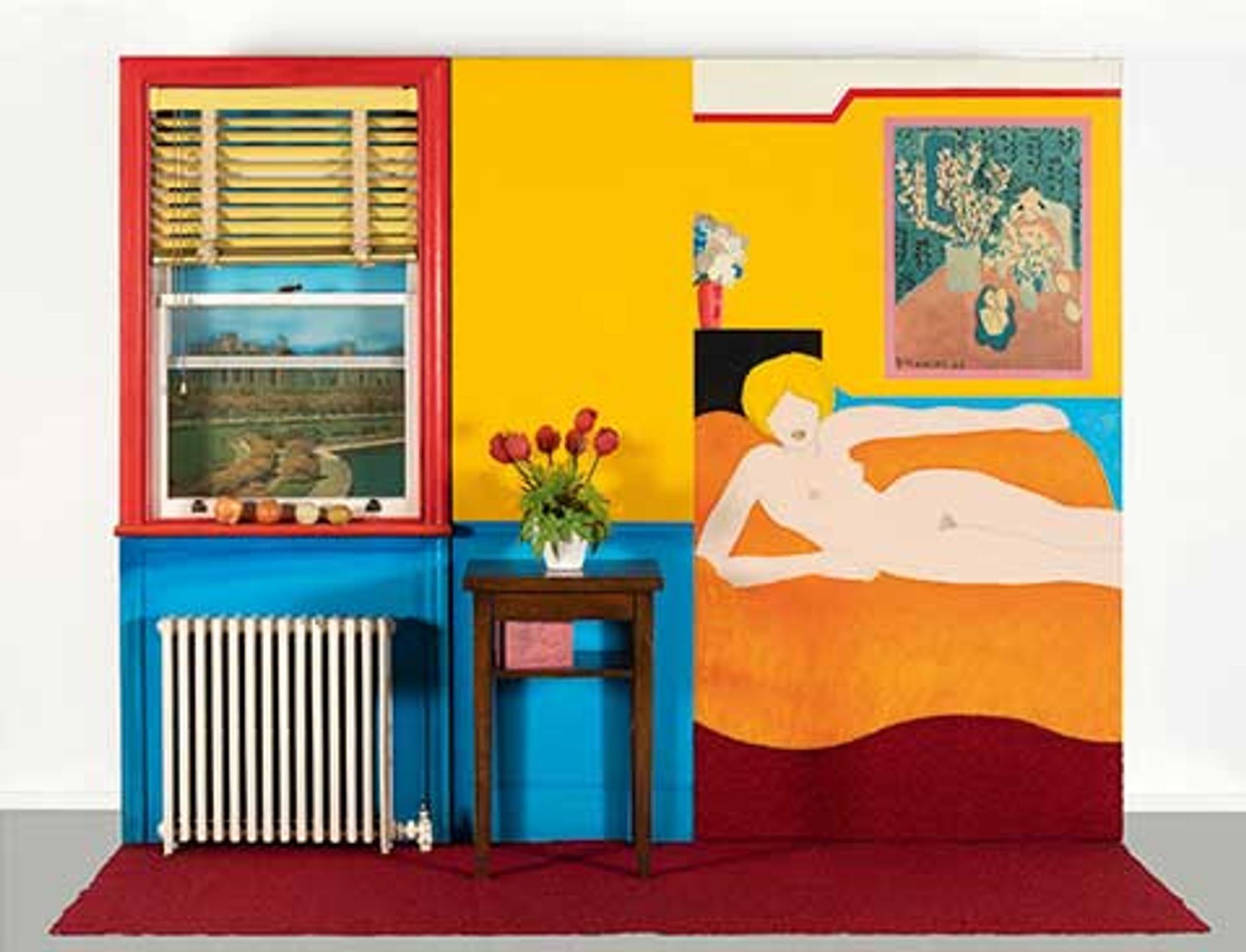

Great American Nude #48 (1963) by Tom Wesselmann infuses the artistic tradition of the nude with the iconography of Pop art

© Adagp, Paris, 2024; photo © Primae/Louis Bourjac

Tom Wesselmann’s fraught yet fruitful relationship with Pop art

Throughout his life, the late American painter Tom Wesselmann (1931-2004) repeatedly rejected the label of “Pop artist” because he considered its critique of consumerism irrelevant to his own work. Still, he remains an emblematic figure of the movement’s marriage between fine art and popular culture, having infused the classical traditions of art history—particularly the nude, the landscape and the still life—with the iconography of his time. From the 1950s on, Wesselmann embraced the aesthetics of comic strips, commercial advertising, Hollywood movies and more.

At the Fondation Louis Vuitton, the curators Dieter Buchhart and Anna Karina Hofbauer will stage Pop Forever, Tom Wesselmann &… (17 October-24 February 2025), a giant survey placing more than 150 of the artist’s works in dialogue with 35 artists from Pop art’s past, present and future. Expect to see Wesselmann’s silk-screened Great American Nudes series alongside the work of American contemporaries including Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol, as well as Wesselmann’s large-scale collages next to the Dadaist precedents of Marcel Duchamp and Kurt Schwitters. His recurring imagery of mass-produced consumer goods will also resonate with works by Jeff Koons and Ai Weiwei, while his nudes and interiors will commingle with newly commissioned works by next-generation artists such as Derrick Adams, Tomokazu Matsuyama and Mickalene Thomas.