It was two months after 7 October 2023 before the artist Tal Mazliach could face a blank canvas, and when she finally did, the words that poured out of her were: “But I got out alive.” The phrase wallpapers the background of a painting she wryly titled War Decorations 1 (2023), repeating like an ambivalent affirmation.

“It doesn’t say, ‘I’m grateful that I made it out alive,’” says Amit Shemma, the assistant to the Tel Aviv Museum of Art’s chief curator and curator of the recently opened exhibition Tal Mazliach: War Decorations (until 11 January 2025). “It almost has a double meaning—okay, I got out alive, but what do I do with my life now, after that intense experience?”

Mazliach’s experience was surviving the Hamas attack on Kibbutz Kfar Aza, the artist’s birthplace and home, an assault that resulted in the murder of 62 and kidnapping of 19 residents. For 20 hours she was frozen in a fetal position, alone in her home’s safe room, which doubles as her makeshift studio. Mazliach was then evacuated to temporary housing and later to her brother’s home in Matan, a town in central Israel near the West Bank border.

Dizzying detail

War Decorations 1 was the first of what grew into a series of 22 chronologically numbered paintings bearing that sardonic title, all being publicly debuted now at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. The exhibition, one of three at the museum marking the anniversary of 7 October, also includes two 2010 Mazliach paintings from the museum’s permanent collection and five works created after War Decorations. The other shows that opened in tandem are ’73-’23: Video Salon Between Two Wars, an anthology of 52 Israeli video works produced in connection with the Yom Kippur War of 1973 and the current war, and I Don’t Want to Forget, an exhibition of works by 25 Israeli artists created in response to 7 October, from the Mareva and Arthur Essebag collection.

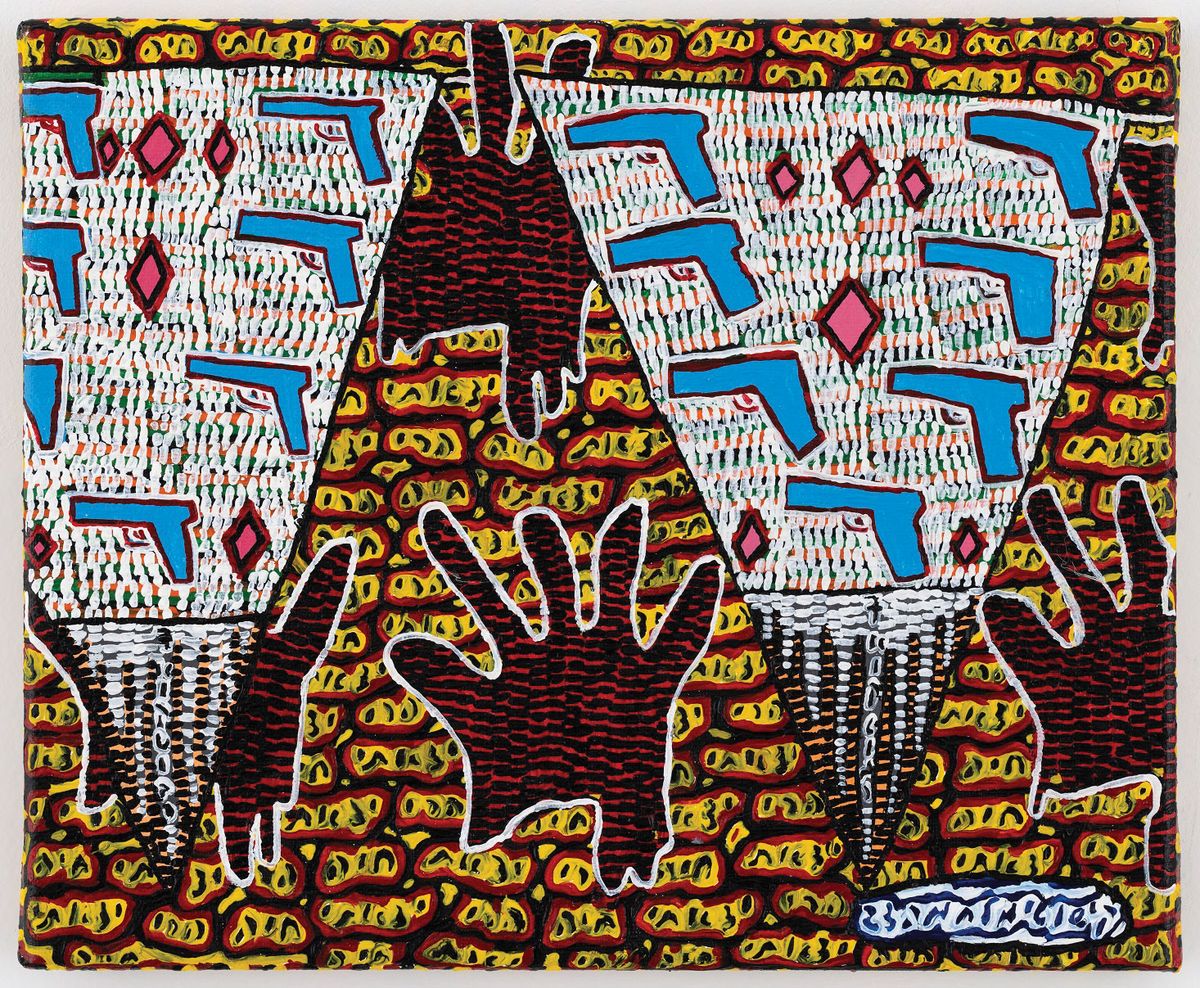

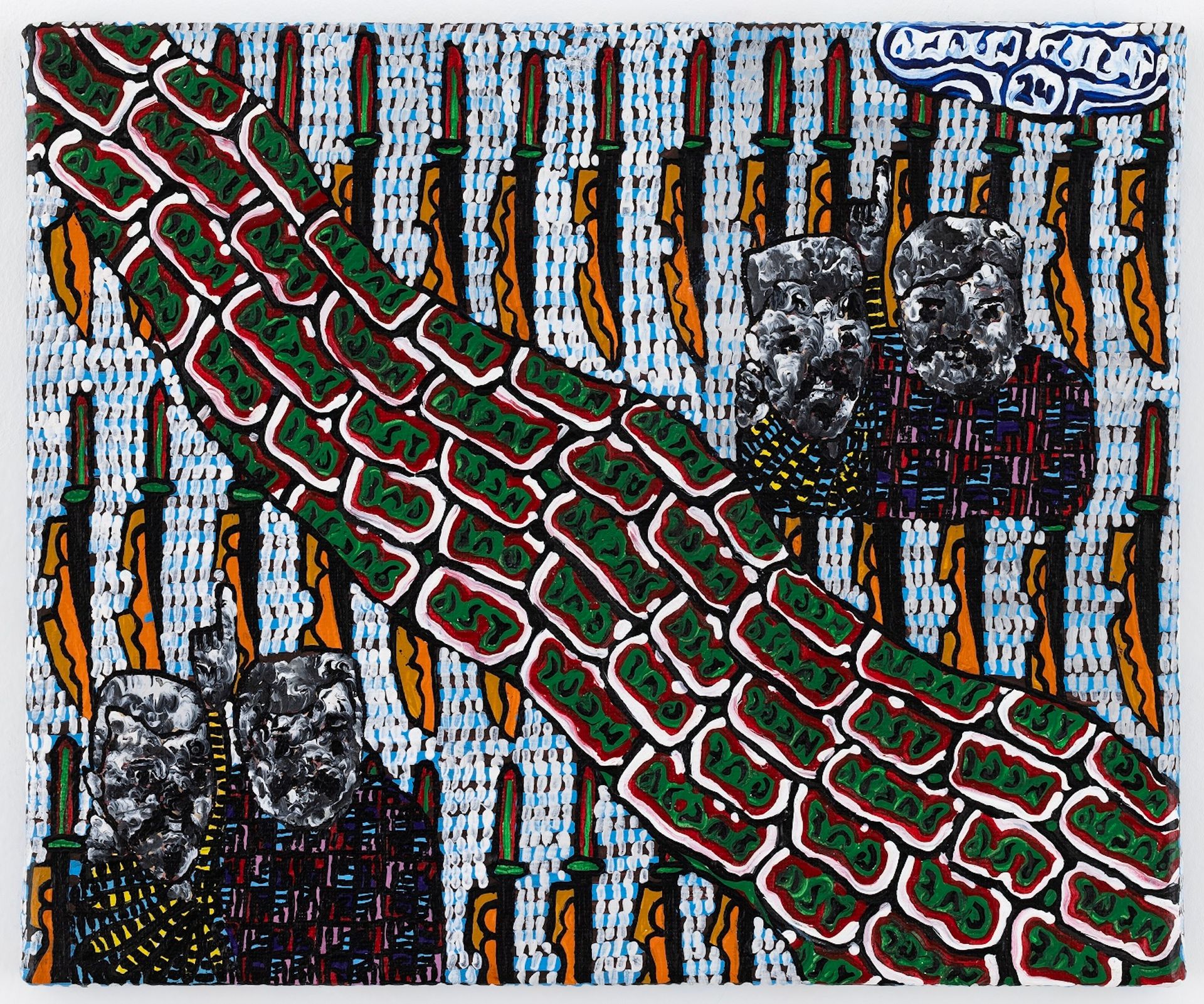

All the works in the War Decorations series hold complexity and dizzying detail. Mazliach always incorporates text, like stream-of-consciousness narration that ranges from a single word to a few sentences. “And they arrived and they arrived,” says the third work in the series, ambiguously referencing either Hamas or the Israeli Defense Forces soldiers who rescued her from her home; “I don’t recognise the noises,” says another; the seventh painting reads: “I had a home. A home I had.” The museum produced flyers with transcriptions of the paintings’ texts in Hebrew, Arabic and English so visitors can decipher them.

Mazliach’s words interrupt any potential visual silence. “I need there to be lots and lots of things,” Mazliach is quoted saying in the catalogue of her previous solo exhibition at the museum, in 2010. “Lots of lines, faces, recurrent texts, because when there is so much then you don’t see… so it’s a form of protection.”

Tal Mazliach, War Decorations 10, 2023 Courtesy the artist and Alon Segev Gallery, Tel Aviv. Photo: Elad Sarig

The artist still needs this patterned protection, even though the subject of War Decorations is nothing new to her. Mazliach has been creating work about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for over two decades, often using the colours of the Palestinian and Israeli flags, for example, or depicting weapons and the Separation Wall dividing Israel and the West Bank. In 2009 she painted two self-portraits in defensive positions bracing against Kassam missiles from Gaza. In the first one, words on her clothes read “I shall be ready” and in the second, the elastic band on her shorts repeatedly says, in what now seems like a haunting premonition of the current hostage situation: “I went to Gaza and came back.”

What is novel for Mazliach, though, is that she is not imagining a possible disaster but one that actually happened. “I wouldn’t say that this series contains new elements except for the story that lies behind them,” Shemma says. “The big change is in her words. The texts come entirely from her experience.” There are also differences in media and format, due to the reality of being away, still, from her home studio. Instead of her usually large oil paintings on wooden panels, War Decorations is rendered in acrylic on small canvases.

New imperatives, new practices

Mazliach’s exhibition has added significance due to its location. Last October the plaza outside the museum became Hostages Square—a meeting place for families of hostages held in Gaza and those supporting them through protests and rotating installations (including one titled Cypress Path by the renowned artist Michal Rovner). “Over this entire year, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, because it’s near Hostages Square and because of the situation here, needed to change its exhibition schedule and adopt a different practice,” Tania Coen-Uzzielli, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art’s director, tells The Art Newspaper.

Tal Mazliach, War Decorations 12, 2024 Courtesy the artist and Alon Segev Gallery, Tel Aviv. Photo: Elad Sarig

Since last October, the museum has co-operated with the Hostages and Missing Families Forum in various ways and several shows have touched on the conflict. These have included Into the Unknown,a compilation of Israeli video works screened facing Hostages Square; Shattered Hopes and Roads Not Taken, charcoal drawings by Netta Lieber Sheffer imagining alternatives to the existence of the state of Israel; and Cascade, a site-specific installation by the Arab Israeli artist Muhammad Abo Salme made from thousands of metres of suspended metal bead chains, the kind used for dog tags and necklaces in solidarity with the hostages.

In thinking of the enormity of the tragedy of 7 October and all that has unfolded since, Coen-Uzzielli adopts the message that Jon Polin, the father of the recently murdered Israeli American hostage Hersh Goldberg-Polin, shared at August’s Democratic National Convention in Chicago: “In a competition of pain, there are no winners.”

“This is our message,” Coen-Uzzielli says of the museum’s approach. “Here, we’re showing one type of pain, the pain of Tal Mazliach, which is a personal pain that I assume is felt here and there.”