A new documentary about the French American artist Niki de Saint Phalle (1930-2002) had its world premiere on Friday (27 September) at the Vancouver International Film Festival. The film, Viva Niki, is a joyous celebration of De Saint Phalle’s life and work directed by Michiko Matsumoto. It focuses on her monumental Tarot Garden (1978-98) in Tuscany, the Stravinsky Fountain (1983) in Paris and the many iterations of her nanas series of large-scale female form sculptures. De Saint Phalle’s work is widely known and celebrated, but the film’s most compelling revelations concern the artist’s personal life—especially her mental health issues stemming from childhood abuse—and her international celebrity.

De Saint Phalle, as they say, is big in Japan, and not only with Matsumoto, a photographer and film-maker who first met the artist at her home outside of Paris in 1981. The collector and fan Yoko Shizue Masuda opened an institution devoted to De Saint Phalle’s work, the Niki Museum in Nasu, in 1994 (it closed in 2011). Several of the artist’s whimsical sculptures—including an elephant, a cat and a camel—are on display on the Japanese island of Naoshima at the Benesse Art Site, and three phantasmagorical works hold court in the plaza of the Tokyo headquarters of the Benesse Corporation. Her 1968 work Miss Black Power, inspired by the Civil Rights and Black is beautiful movements, stands tall in the Hakone Open-Air museum in the Kanagawa prefecture.

Niki de Saint Phalle's Tarot Garden (1978-98) Artwork ©2024 Niki de Saint Phalle/NCAF. Photo: ©2024 Michiko Matsumoto

The Japanese sociologist and director of the Women’s Action Network, Chizuko Ueno, appears in the documentary. She says that De Saint Phalle’s powerful 1972 film Daddy, in which the artist alluded to the sexual violence she suffered as a child (an experience she confirmed in her 1994 book Mon Secret), resonated with her immediately.

“I saw the film and said, ‘Wow this is me!’” she tells Matsumoto. “So I published an essay called ‘Daddy’s Girl’ about how women attempt to escape the influence of their fathers.” She was also deeply affected by De Saint Phalle’s performative shooting paintings, in which the artist aimed a gun at male figures stuffed with bags of red paint that would explode accordingly.

“It was such a marvel to me that a neurotic man-hater who made performance art like that went on to produce the joy-filled nanas,” Ueno says in the film. She subsequently wrote several essays on De Saint Phalle and used an image of the artist’s infamous sculptural installation Hon (1966) on the cover of one of her books.

“Niki wrote that if she hadn’t become an artist, she would have become a terrorist,” Ueno says in the film. “I think that kind of animosity toward the world strikes a chord with many women. But from this background she went on to heal herself through art.”

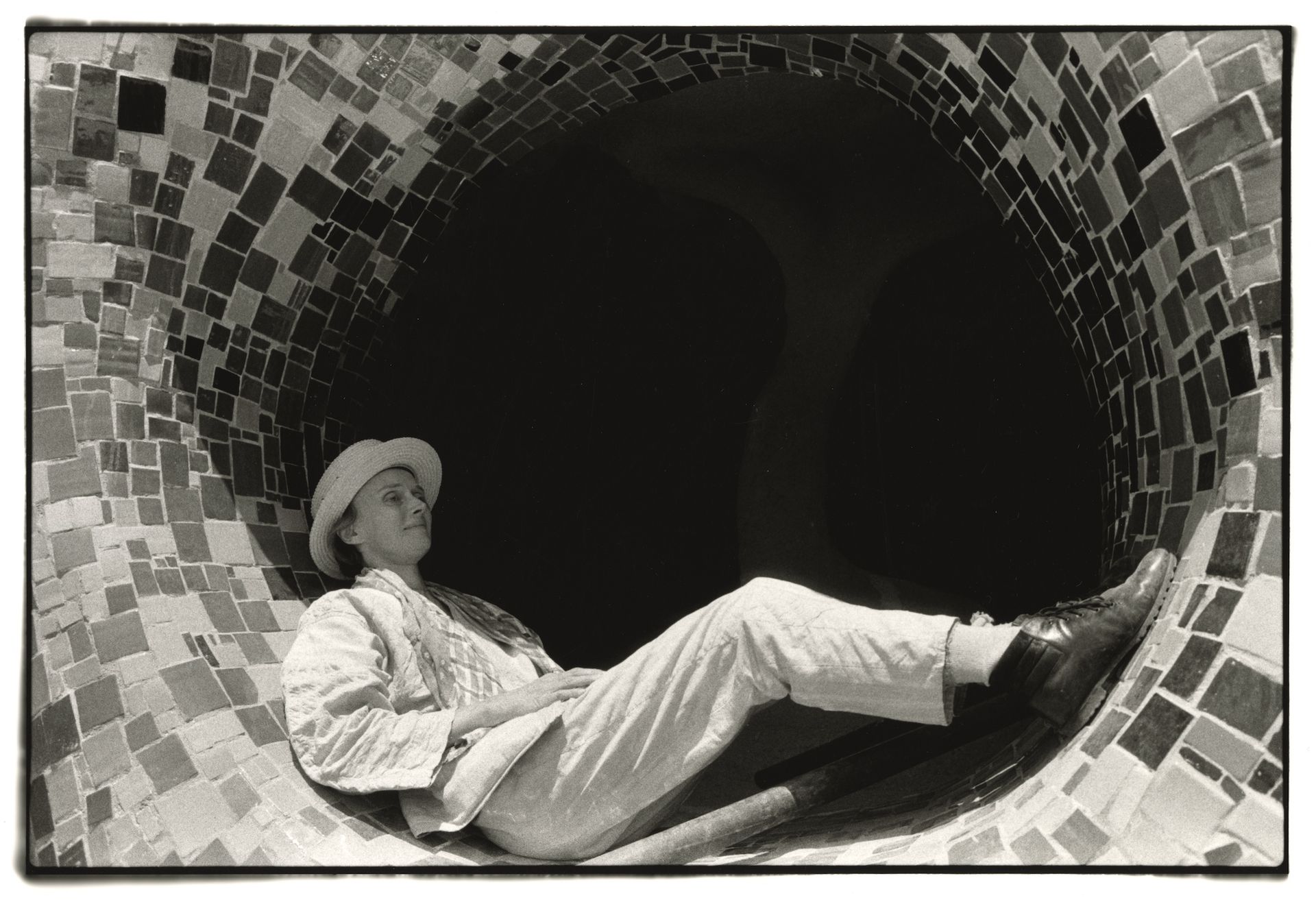

Niki de Saint Phalle in 1985 Photograph © 2024 Michiko Matsumoto

Ueno’s insights encapsulate the film’s intention, to meld the personal and the artistic in its exploration of De Saint Phalle’s legacy. Her work embodied many seeming contradictions, marrying serious feminism with playful frivolity, the decorative with the disturbing and, especially in the case of her last great project the Tarot Garden, the ecclesiastical with the Disneyesque.

There are many lovely moments in this film, including footage of children all over the world playing in and around De Saint Phalle’s sculptures. The sequence on the Stravinsky Fountain near the Centre Pompidou features footage of Parisians enjoying the fantastical sculptures mechanised for maximum waterplay, as well as some rare stills of an ailing de Saint Phalle in front of her work. (The artist suffered from emphysema caused by exposure to chemicals in sculpture materials.) This section also explores her relationship with her long-time collaborator, the artist Jean Tinguely.

In the film’s latter section features the artist’s daughter, grand-daughter and great grand-daughter, all of whom are involved in the Niki Charitable Art Foundation and its mission to preserve De Saint Phalle’s work. The scenes shot in her final home of San Diego, where she went for the fresh air when her lungs began to weaken (and where she left a considerable local cache of public sculptures), are moving and speak to the matrilineal connections bequeathed by an artist whose work celebrated the divine feminine.

Niki de Saint Phalle, Stravinsky Fountain, 1983 Artwork ©2024 Niki de Saint Phalle/NCAF. Photo ©2024 Michiko Matsumoto

The film also highlights the artist’s gradual shift from the sculptural to the architectural: from the giant Hon installation at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm—featuring a theatre and aquarium accessible by passing through a giant female figure’s vagina—through to her Dragon (1973) playhouse in Belgium, commissioned by the collector Roger Nellens (who also appears in the film). We learn that special overnight guests in the fully equipped playhouse included Keith Haring, who painted a fresco along the staircase leading to the upper level. In many ways, the experience she gained designing the Dragon paved the way for the Tarot Garden, which was also informed by Antoni Gaudí’s Parc Güell in Barcelona.

“When I visited the Dragon with Niki, she told me that to an innocent child a monster can be a friend, but that adults can only be friends with monsters if they have a playful heart,” Matsumoto says in the film.Viva Niki sensitively navigates between the artist’s innocence betrayed and the many creatures she simultaneously slayed and created.