The eminent Italian-American curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev remembers being on a plane once, in the early 2000s, with the Italian artist Emilio Prini, who was yelling. Prini was one of the 13 artists whom Germano Celant had observed in 1967 working with leaves and trees and breath and decay, and promptly coined the term Arte Povera. Four decades on, Prini was still going strong and making work. Yet all the art establishment at the time seemed interested in were the greatest hits from his 20s.

Prini’s contradictory stance notwithstanding (he had agreed to be in the show after all), Christov-Bakargiev understood the frustration. “For a group of artists who believe in life and in energy transferral and in the being here, in the phenomenological experience of presence and bodily presence, to tell them, ‘We’re only showing works until 1972’ is crazy,” she says.

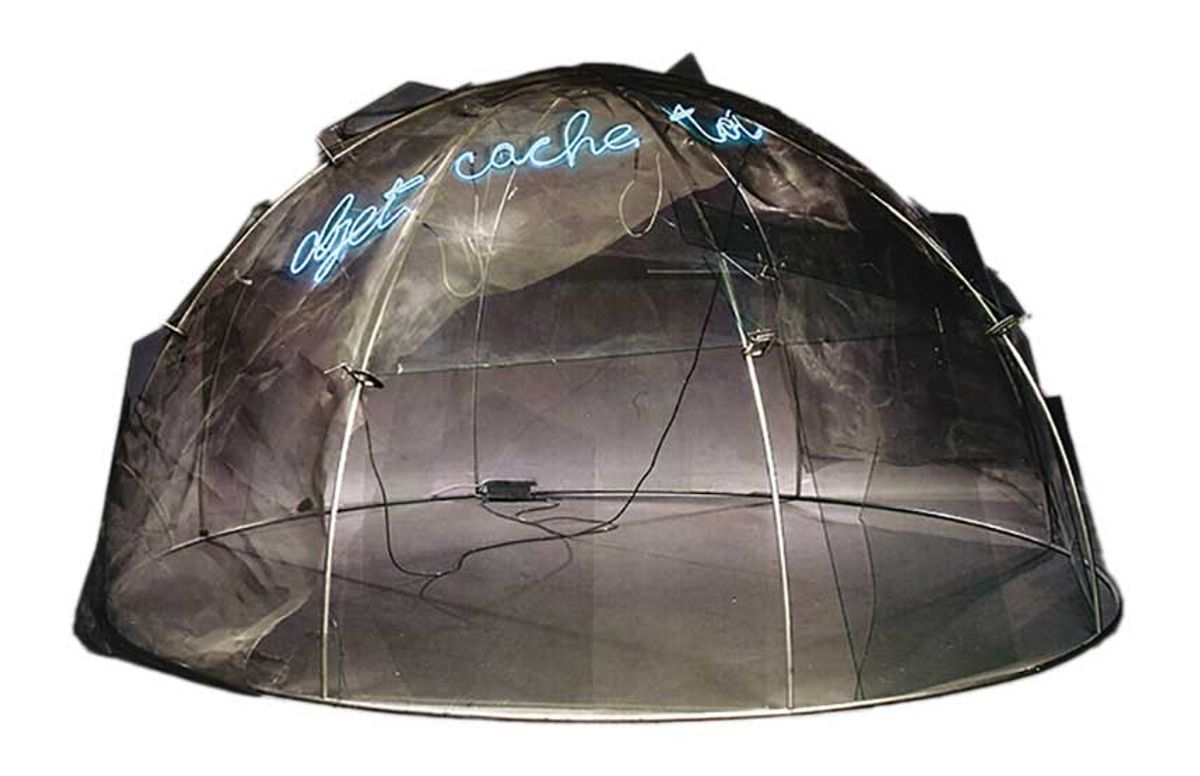

The curator, a career-long champion of Arte Povera, stepped down as the director of Castello di Rivoli Museum of Contemporary Art in Turin, effectively the group’s home, in 2023. But when Emma Lavigne, the director of the Bourse de Commerce in Paris, asked her to curate a major show centred around the Arte Povera works in the Pinault Collection, she promptly delayed her retirement. Opening this month, the Bourse de Commerce exhibition provides a staunch corrective to any blinkered take on artistic longevity. It features new works, such as Giovanni Anselmo’s last Particolare projection work, completed just before his death in December 2023, and premieres others: the glowing neon numbers of a previously unrealised edition of Mario Merz’s Fibonacci sequence will be inserted into the building’s façade. The exhibition will also spotlight multiple firsts: Anselmo’s first Direzione, Merz’s first igloo, Giuseppe Penone’s first sculpted tree and Pier Paolo Calzolari’s first icing sculpture, which Christov-Bakargiev says “almost nobody has seen”.

With this show, which Lavigne describes as "a landscape to survey”, François Pinault wanted to highlight the prominent role Arte Povera holds within the 10,000 works he has collected over the past five decades. His goal with the collection at large is to show how artists chime with the present. As Lavigne says, among Arte Povera artists, there is a rich harmony "between archaism and political conscience, between nature and plastic", which resonates with what younger artists today are looking for—different tools for processing our globalised and technologically advanced era.

Arte Povera as a ‘state of mind’

To the 50 or so items from the Pinault Collection, the curator has added over 200 more, including several pieces by artists who either predate Arte Povera, such as Constantin Brâncuși’s The Kiss (1907) and an Etruscan vase from the Musée du Louvre, or who have developed in unison with it. Cue William Kentridge with what Christov-Bakargiev calls his “animazione povera”, and David Hammons with his snowball sale performance piece and his assemblages.

“Arte Povera is almost a state of mind,” Christov-Bakargiev says. “It has to do with what is an artwork and what makes life meaningful. And what is an artwork is certainly not a dead chunk of material.” On the floor of the lobby will be Marisa Merz’s Untitled (1997), a diminutive lead fountain in the centre of which is a small violin sculpted of white paraffin that the curator hopes no one will step on. The work of art, though, is really neither the wax violin nor the lead basin, Christov-Bakargiev says, but the way the magnet suspended from the ceiling causes the water to fall back on itself in the shape of a heart. “When you turn it off at night, there’s no artwork,” she says.

Merz draws with magnets, Calzolari with ice and Penone with time. And as long as you are standing right there, you will get to see it.

• Arte Povera, Bourse de Commerce—Pinault Collection, Paris, 9 October-20 January 2025