To mark the 300th anniversary of the birth of George Stubbs, one of the greatest 18th-century British artists and a timeless master of equestrian and animal portraits, four of his finest paintings have returned to Wentworth Woodhouse—the Yorkshire mansion where they were painted in 1762 for Charles Watson-Wentworth, second Marquess of Rockingham, a wealthy landowner, amateur scientist, collector, classicist and future prime minister. These canvases are the central exhibits in Beneath the Surface: George Stubbs & Contemporary Artists, a show that places pictures by Stubbs with studies of the horse by living artists including Mark Wallinger, Ugo Rondinone and Tracey Emin.

This ambitious and eye-opening exhibition is important for the way it places Stubbs in context, of both the house and its park and the contemporary artists who have engaged with his legacy and with the portrayal of animals. This double context sheds light on the emotion and personality present in Stubbs’s polished, scientifically accurate, renderings of both animal and human subjects; he emerges powerfully as an artist who grew to be as accomplished as Thomas Gainsborough or John Singer Sargent by teaching himself his trade through years of close observation and constant application in a process worthy of Monsieur “il faut travailler” Auguste Rodin himself. Beneath the Surface is also central to the future of the house, as the most ambitious exhibition that the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust has mounted since acquiring the house—with assistance from a special government grant—and taking on responsibility for this important historic building in 2017.

Wentworth Woodhouse is made up of two main ranges: the west front, a large early 18th-century Baroque house (above), connected by a central courtyard to a very large mid 18th-century east front (top), 600 feet in length Photographs: Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust

The house’s chequered mid-20th-century history has been captured in Catherine Bailey’s 2008 page-turner Black Diamonds (visitors can this year join special “Black Diamonds” tours of the house). The heirs to Stubbs’s patron Lord Rockingham, the Fitzwilliam family—whose large holdings of “black diamonds” coal were nationalised in the 1940s—sold the house in 1989 after parts of it had been home to two educational institutions over four decades. Two private owners then threw themselves into its preservation, in the face of insurmountable odds (and costs). The house is famously gigantic—a large early 18th century Baroque house linked by a set of courtyards to an even larger mid-18th century Palladian palace, spread over a total of 2.5 acres with an east front 600 feet in length, with commanding views to east and south. A stable block of matching scale, designed by John Carr of York, originally built to house 84 horses and teams of grooms to tend them, stands a few hundred yards from the house.

Wentworth Woodhouse as a home for curated art exhibitions

As an historic building, Wentworth Woodhouse is as important as any other great British country house of its era—Blenheim, Stowe or Chatsworth—but with its celebrated collections of furniture and paintings almost all gone, the near-empty house serves both as a challenge and an opportunity. The succession of state rooms, with bare walls and floors, but fireplaces, doors, panelling, classical plaques and some statuary still intact, make ideal galleries for an imaginative curator.

Jennifer Booth, the house’s exhibition and interpretation manager, tells The Art Newspaper that exhibition planning has been based on research with the local community, schools and other stakeholders, a programme that revealed a demand for shows that mix the historic with the contemporary and that challenge the audience. In 2023, the house saw excellent footfall for a display of Grayson Perry’s tapestry work The Vanity of Small Differences (2013) last summer. “Putting something contemporary” in the lofty panelled state rooms, Booth says, “gave them a whole new dimension”. When visitors understood the connection between The Vanity of Small Differences and William Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress sequence, Booth says, “it transformed the experience for them”.

Beneath the Surface is the house’s first exhibition to operate on two significant levels: as part of the strategy to make the house a cultural powerhouse for the north of England by 2030; and to work with loans of great pictures that once hung in the house. This is the first exhibition in the house to benefit from the government indemnity scheme, allowing the trust to borrow works both historic and contemporary.

Joining the indemnity scheme, which sets particular challenges for those in charge of a listed building, has opened up Wentworth Woodhouse, says Victoria Ryves, head of culture and engagement, “to so many possibilities [with art] that was once displayed here on the walls. It’s really bringing things home.” “We're also noticing,” Ryves says, “that, with the way that we've presented works, people are commenting more on the architecture in those rooms. It’s encouraging them to see those rooms as they would have been rather than as a blank canvas.”

Three works by George Stubbs installed in the Van Dyck Room at Wentworth Woodhouse. Under the terms of the government indemnity scheme applied to a listed building, the pictures are hung on chains from existing holes set into the historic panelling Photograph: James Mulkeen

Stubbs the protomodern artist

It seems hard to believe, at a time when Stubbs’s reputation stands as high as it does, that as recently as 1957, it took the far-seeing Bryan Robertson’s staging of an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, in east London, to bring Stubbs to the serious attention of a new generation of critics. (Robertson had done the same rehabilitatory work at the gallery in 1952 for JMW Turner, whose late-period abandonment of “form” had been attacked by the all-too influential Roger Fry in the 1930s.)

In the succeeding decades, the US banker Paul Mellon’s amassing of a remarkable collection of Stubbs’s work—with 200 pictures left to the Yale Center for British Art and further benefactions to museums including Tate Britain—and the work of scholars such as Basil Taylor and Judy Egerton, the author of the 2007 Stubbs catalogue raisonée, anchored the artist’s place in the narrative of 18th-century British art. So that when Stubbs’s most arresting canvas Whistlejacket (a portrait of a half-rearing champion racehorse painted for Rockingham at Wentworth Woodhouse in 1762) came into the collection of the National Gallery, London, in 1997 the ground was laid for the acceptance of this masterpiece as a timeless work; and an inspiration for contemporary artists. And for Stubbs to be recognised as an artist of the first rank who, with Whistlejacket’s swift but appraising gaze of his audience, reveals himself a master of psychology (human or animal), rather than “just” a great painter of horses.

The Whistlejacket Room at Wentworth Woodhouse, shown before the installation of Beneath the Surface, with a copy of Stubbs's 1762 painting Whistlejacket in the place where the artist's masterpiece once hung Photograph: Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust

Whistlejacket has stayed at the National Gallery for that institution’s bicentenary celebrations and the artist’s tercentenary—it will keep its axial pride of place when the collection is rehung over the next seven months—but a copy of the painting has long since been painted where the picture once hung in the Whistlejacket Room at Wentworth Woodhouse, one of the four spaces devoted to Beneath the Surface. Wallinger has lent a version of Ghost (2001) his celebrated remediation of Whistlejacket: a monochrome negative image of the stallion with a narwhal’s tusk added in picture editing software to create a mythical reimagination of stallion as unicorn.

A classic remediation: Mark Wallinger, Ghost (2001) Courtesy of the artist

By showing some of Stubbs’s finest works in the house they were painted for and seeing them through a Wentworth Woodhouse prism, with intelligence and verve, Beneath the Surface sheds a collective light on why Stubbs’s work has a universal, contemporary relevance, three centuries after his birth in Liverpool on 25 August 1724.

Stubbs the master of anatomy

The exhibition opens on the ground floor, with a Stubbs Hub in the old hall that introduces the artist and houses a family-oriented interactive programmes devised by local secondary school children. The hub includes examples of work from a Stubbs trail devised by Richard Johnson, a local landscape artist, who knew the estate intimately in his youth, through his friendships with the 10th Earl Fitzwilliam’s gamekeeper, and who has worked out where two of the paintings on show in the house are set. This summer he has taken 20 members of ArtWorks South Yorkshire, which works with adult artists with learning disabilities, to reimagine the paintings from where Stubbs had worked 262 years before.

Visitors then proceed up the Oak Stairs and through to the state rooms on the piano nobile of the east wing where their first encounter is with Stubbs the prodigious anatomist. An edition of Stubbs’s The Anatomy of the Horse (1766), on loan from a private collection and said to have been the copy that Lord Rockingham subscribed for, is open on one of the engravings that Stubbs based on drawings which he made from methodically posed and (temporarily) conserved horse cadavers, at a farm house in Lincolnshire, over a period of 18 months in 1756-57. That house is thought to have been lent to the largely self-taught Stubbs by Lady Nelthorpe, one of his early supporters. She is the subject in a double portrait with her late husband John Nelthorpe, of around 1745, that is the earliest known surviving work by Stubbs. As with his earlier extended study of human anatomy in the city of York, Stubbs observed the equine cadavers with a thoroughness that feels driven by his awareness, two years after he had made a rather brief visit to Rome, of how important anatomical study had been in the formation of the genius of both Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarotti.

Even seen through the glass of a vitrine, the effect of this engraving of a horse’s right flank, with an exquisitely rendered mesh of skin, veins and muscle immediately below, is electrifying. A combination of the material quality of the paper and masterly execution take the breath away. Encountering this work is a reminder why Stubbs’s original equine anatomical drawings (24 of which are now in the collection of the Royal Academy of Arts in London) caused a sensation in London in the late 1750s. Those drawings, which have caused him to be dubbed an “English” or “Liverpudlian Leonardo”, led to a commission in 1759 from first the Duke of Richmond at Goodwood House, in Sussex—a series of hunting scenes that are still to be found in the Goodwood collection—and then from Rockingham and other leading Whig grandees. Such was the stampede for his services from horse-loving aristocrats that Stubbs had to finish the engravings for the book, a publication that earned him an international reputation, by working all hours, first thing in the morning and last thing at night.

Stubbs shows a shared purpose between man and horse

The first Stubbs oil painting the viewer encounters, in the state room corridor, is perhaps the least known of the four Wentworth Woodhouse commissions that have been lent to the exhibition from a private collection. But it is far from being the least affecting. Both racehorse and jockey in Portrait of Scrub in a Landscape with John Singleton Up (1762), have a poise and acuity of facial expression that is a development of what stands out in Stubbs’s human portraits of the previous 15 years—the works that gave him the painterly grounding, and command of individual character, for his first flood of equestrian masterpieces between 1759 and 1762.

An installation view of Beneath the Surface in the state room corridor at Wentworth Woodhouse. Daniel Quigley's Flying Childers and Dimple on a Racecourse, Other Racehorses Beyond is presented in contrast to emphasise the greater sophistication of Stubbs's contemporaneous Portrait of Scrub in a Landscape with John Singleton Up (1762) to the right Quigley: Heritage Doncaster. Stubbs: private collection. Photograph: James Mulkeen

The artist’s empathy for both man and animal, each treated as a non-generic, particular individual, with palpable emotion behind the eyes, is unmissable. Scrub was considered small for his breed, at just 14 hands, and had won his last race, one of eight wins in an 11-race career, when he took the four-mile Great Subscription Plate at York, in 1761. The artist’s patent sympathy with both subjects is enhanced by learning that Scrub, like the three other works painted for Wentworth Woodhouse, hung not in a room of parade but in Rockingham’s dressing room, and that the horse was given to Singleton—who trained and rode the majority of Rockingham’s horses, including the champion Whistlejacket—to be cared for after it retired from racing.

The painting speaks of shared purpose between horse and jockey, a common gaze. This quality of common purpose is reminiscent of Stubbs’s Otho, with John Larkin up (1768), part of a meditative one-room show Stubbs and Wallinger: The Horse in Art at Tate Britain (until 6 July 2025), where both rider and steed are captured on Newmarket Heath, the headquarters of horse racing, looking into an evening sun, fixed on something far beyond the confines of the painting’s gilded frame.

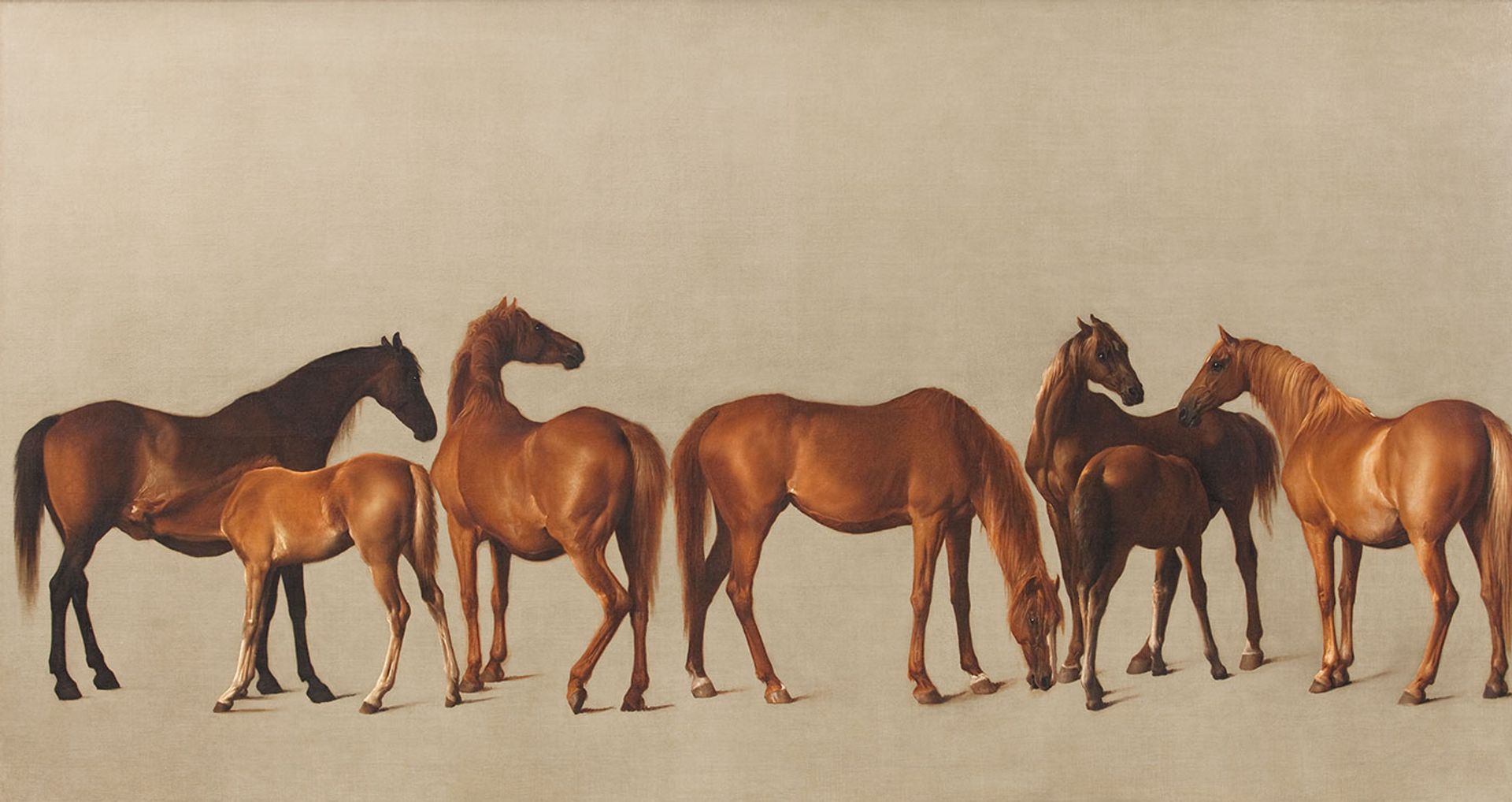

George Stubbs, Mares and Foals with an Unfigured Background (1762) Private Collection

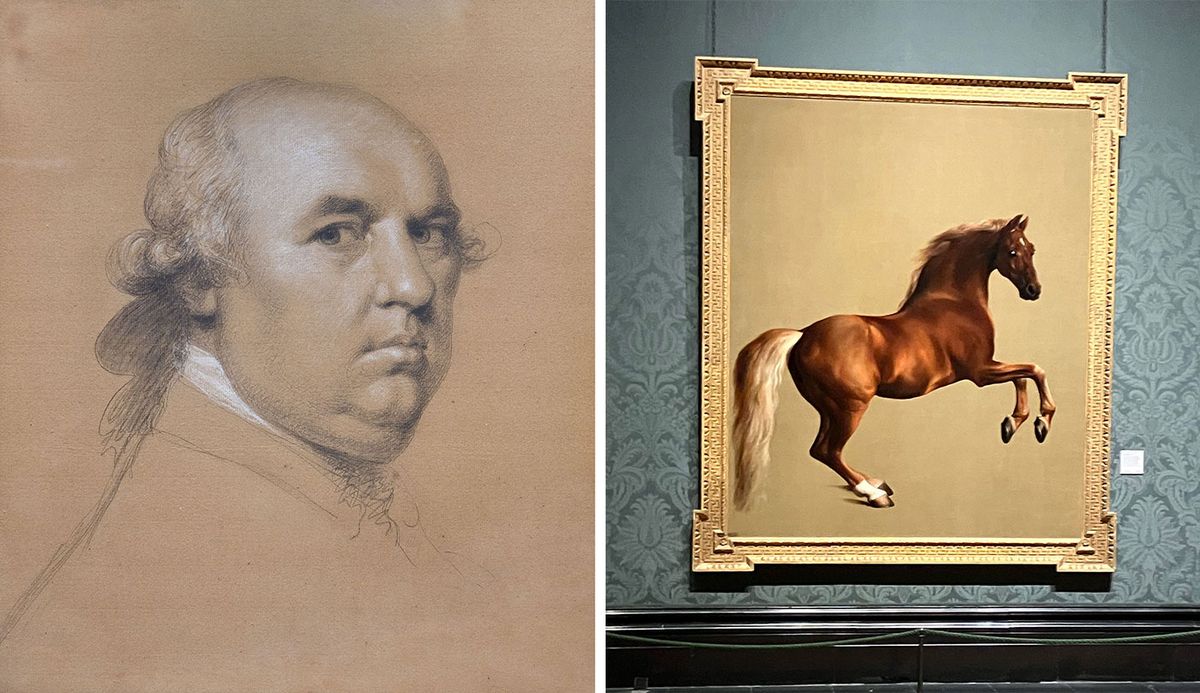

The star canvases in the private loans to Wentworth Woodhouse are two group portraits by Stubbs, painted for the house in 1762: Mares and Foals with an Unfigured Background and Whistlejacket with the Head Groom Mr Cobb and Two Other Principal Stallions. Like Whistlejacket in the same year, these canvases have a plain, unfigured, background, in a colour, that has been described by critics variously as “honeyed beige”, “olive” or “fawn”. The plain background subtly complements the fine gradations of chestnut and bay in the coats of the equine stars, arranged frieze-like in both paintings. It is a tonal relationship that tells beautifully in the well-lit Van Dyck Room at Wentworth Woodhouse, a relationship whose subtlety can be lost in even the finest colour reproduction. (The name of the room is a reminder of the collection formed by a former owner of the estate, Rockingham’s great great grandfather Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford—chief political supporter of King Charles I, notoriously attainted by Parliament and executed in 1641. The Van Dyck collection once included the famous, Titianesque, Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, with Sir Philip Mainwaring (1639-40) and a full-length portrait of Queen Henrietta Maria.)

George Stubbs, Whistlejacket with the Head Groom Mr Cobb and Two Other Principal Stallions (1762) Private Collection

Both these frieze group portraits carry an emotional charge. There is a tenderness of community between mares and their feeding foals expressed by the compositional interlacing and overlaying of the necks and legs of a peaceable herd. In the three stallions painting, each animal is posed separately, in a more formal sequence but, standing to the right is the famously temperamental and explosive Whistlejacket, calmed for a moment by the close embrace of his groom Josiah Cobb. Cobb all the while looks directly, candidly, at the artist.

Emotional charge: detail from George Stubbs, Whistlejacket with the Head Groom Mr Cobb and Two Other Principal Stallions (1762) Private Collection

Rockingham’s taste for sculpture

Judy Egerton—whose authority on the artist was grounded on years working in London on Stubbs; at Tate, where she curated a full-scale retrospective of the artist’s work in 1984, then at the National Gallery and the Mellon Research Centre, with its close connection to the Yale Centre of British Art—felt that both the unfigured backgrounds and sculptural arrangement of horses and human in these canvases are testimony to Rockingham’s passion for classical sculpture and exhibiting it against plain backgrounds. At Wentworth Woodhouse, the visitor has a short walk from these paintings down the state corridor to see evidence of that passion in the surviving statuary from the Rockingham and Fitzwilliam collections—a mix of ancient, 18th and 19th-century sculptures—in situ against plain backgrounds in the double height great Marble Hall, created for Rockingham by the architect Henry Flitcroft.

The Marble Hall at Wentworth Woodhouse, where the Rockingham and Fitzwilliam collection of 18th- and 19th-century classical sculpture remains in place Photograph: Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust

As Nicholas Penny explains in an introductory essay to the exhibition catalogue, “the marble copies of the most famous ancient Roman statues, made at enormous cost by leading Italian sculptors, have never left their niches in the Marble Hall” at Wentworth Woodhouse. Nor have the panels set into the hall’s walls designed by the great neoclassical artist and designer James “Athenian” Stuart. Likewise the statuary on the elliptical main stairs added later by John Carr of York, some of it ancient including an imposing Roman statue of Ceres, the goddess of agriculture, acquired in Rockingham’s lifetime, which is thought to have come from the excavation of Herculaneum, near Naples, in the mid 18th century.

A first-century AD statue of Ceres, on the main stairs at Wentworth Woodhouse. It was acquired by the second Marquess of Rockingham, patron of George Stubbs, and is thought to have been excavated at Herculaneum in the 18th century Photograph: The Art Newspaper

Stubbs the painter of dogs and monkeys

The final private loan is Five of Lord Rockingham’s Stag Hounds in a Landscape (1762), another frieze-like composition, but with a fully figured landscape of the park at Wentworth Woodhouse in the background. The picture, catching each hound’s inquisitive, individual intelligence, is one of the finest set pieces in Stubbs’s large output of non-equine animal portraits.

“Biographical information about Stubbs is sparse,” Egerton writes in the opening sentence of her magisterial entry on Stubbs for the Oxford Dictionary of National biography. His personal and professional papers vanished following his death in 1806, making it all the more valuable that a signed receipt from Stubbs has been found in the Rockingham and Fitzwilliam family papers in the Sheffield archives, listing payment for all four of the private loans to Beneath the Surface. It is dated 15 August 1762 and for £194 and 5 shillings and describes “a Picture of five brood-mares and two foals, one picture of Three stallions and one figure, one picture of a figure on Horseback, one picture of five Dogs…”.

Three institutional loans of works by Stubbs exemplify the richness held by museums across Britain. A serene Two Horses Communing in a Landscape (1774), in a consciously sublime setting, comes from the Weston Park Foundation, in Staffordshire. A vivid, much-reproduced, large-format, portrait of Phillis a pointer of Lord Clermont’s (1772) has been lent by Leeds Museums and Galleries (Temple Newsam) and the scene stealing half-startled A Monkey, 1799, is a loan from the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool.

The Two Horses Communing, and their peaceful togetherness, finds an echo in two video pieces, shown in the darkened anteroom, where horses are captured in two very different types of sublime. In Cornered Star, Melanie Manchot shows the titular champion showjumper amide the Brutalist architecture of the post-industrial city of Marl, in northwest Germany. In Stable (2007), Kathleen Herbert released horses into the Gothic spaces of Gloucester Cathedral at night. Beneath their uncanny surfaces, both videos show, like Stubbs’s finest equine subjects, the horse with a life, and mind, of its own.

Sutapa Biswas and Ugo Rondinone both present Stubbsian meditations on the solitary presence of the horse in landscape, be it the English country, the expanses of a desert, or a state room at Wentworth Woodhouse. In the Whistlejacket Room Hugo Wilson, a figurative artist, reimagines Whistlejacket kicking up his hooves from across the room at the reproduction of the Stubbs painting.

Wallinger, meanwhile, one of Stubbs’s greatest artistic champions over the past 25 years, finds magic in the artist on multiple levels in Beneath the Surface: in the mythical with Ghost; in the use and symbolism of the racing colours worn by jockeys in his Mr and Mrs Brown series, which is represented in the show, and in matter of breeding, the development of the thoroughbred racehorse (which was in its early days in the time of Whistlejacket). Wallinger's Half-Brother (Exit to Nowhere—Machiavellian) (1994–95) stands at the centre of the Tate capsule show, a meditation on the thoroughbred industry’s concern with genealogy. It is made up of images of two racehorses, half-brothers born of the same mother, meeting in the middle in a symbolic juncture.

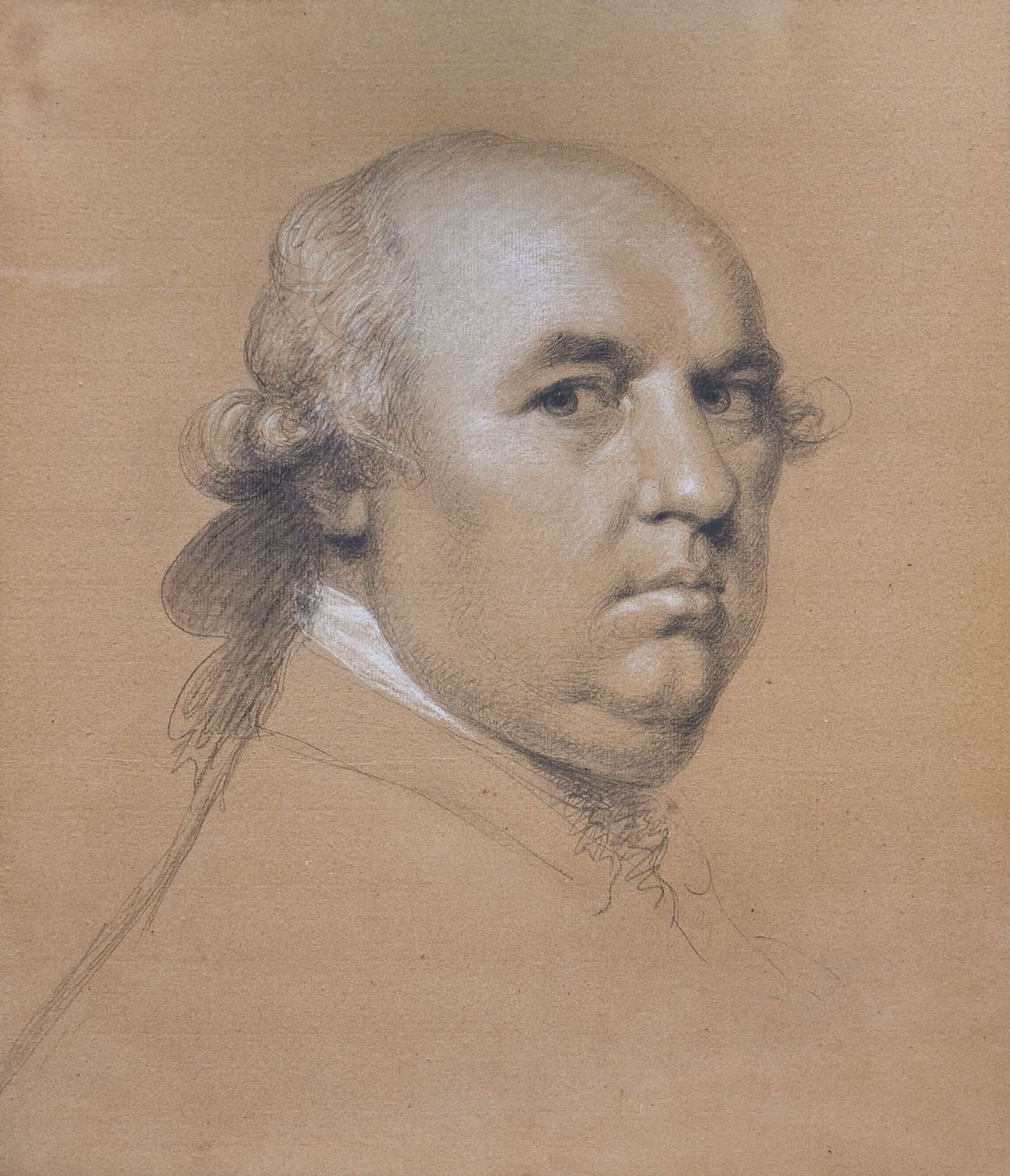

Ozias Humphry, George Stubbs (1777) Private Collection

George Stubbs: the biographical challenge

One of the most memorable moments in Beneath the Surface is meeting the redoubtable visage of Stubbs in 1777, drawn in black and white chalks by Ozias Humphry an established portraitist who also left some intriguing, unpublished, biographical notes on Stubbs, based on conversations from the 1790s. Stubbs’s expression in 1777 is candid, confronting and unamused; the look of a one who knew his own worth, and was also completely himself. Stubbs scholars, including Egerton, have questioned the reliability of Humphry’s notes on Stubbs, based as they are on conversations when Stubbs was over seventy.

Two anecdotes have the ring of truth as each confirms the other’s evidence of the artist’s potential for invincible stubbornness. The first relates to why he walked out on his apprenticeship with Hamlet Winstanley, the Lancashire painter and engraver, in the 1740s. Winstanley had asked him to select a picture to copy from the collection of the Earl of Derby at Knowsley Hall. Stubbs’s first choice, Winstanley had already reserved for himself. His second choice the same. At which point Stubbs parted company with his master and remained self-taught thereafter. The second relates to his relationship with the newly fledged Royal Academy in London. Stubbs was made an associate and asked to submit a diploma painting. He seems to have taken this as an impertinence, citing (imagined) cases when others had been spared from submitting such a thing. He refused to submit such a work and therefore never took up his full role as a full royal academician.

This sense of knowing his own worth is apparent in the Humphry portrait and in Stubbs’s 1781 self-portrait in the National Portrait Gallery. In both he looks directly at and almost through the viewer. That self-possession is also present in his recorded references to undergoing anatomical study, just as Michelangelo and Leonardo had done before him. It also comes across in some of the well-polished dicta recorded in Humphry’s notes.

One of Humphry’s stories—of how Stubbs allegedly left Rome in 1754 without copying anything from the antique—has sometimes tended to minimise the artist’s own agency in developing his style through study of both the antique and Old Masters. Seeing his paintings back in the home of Rockingham, his patron who paid great service to classical models, brings to mind Stubbs’s brilliant sequence of works, in oil, enamels and as engravings, on the subject of a horse attacked in the wild by a lion. As Egerton pointed out, the model for this is unavoidably a celebrated ancient Greek sculpture of a lion devouring a horse which stood in the courtyard Palazzo dei Conservatori at the time of Stubbs’s visit to Rome.

From a classical model: George Stubbs, Horse Attacked by a Lion, 1769, from Stubbs and Wallinger: The Horse in Art, at Tate Britain Photograph: The Art Newspaper

Stubbs’s first version of the subject was a giant canvas commissioned for Rockingham’s London house in 1762. The Tate Britain show includes a small enamel (the artist’s first experiment in the medium) on the subject. It is a side to Stubbs’s work that shows him both adhering to a classical model and pushing towards the sublime in subject matter. These sublime-historical subjects break the confining mould of Stubbs the horse painter a mould that artists and art historians have continued to break in the past half-century.

One other side of Stubbs that feels unavoidable is his dedication to his own training: his studies of human and equine anatomy, his studious work in learning the skills of the engraver and the etcher. That dedication is wonderfully captured in a pencil drawing, thought to be by George Dance, of Stubbs “in the act of etching”. The artist is bent over his desk, totally absorbed, caught on the wing in a moment of concentrated craftsmanship.

A template for the future of Wentworth Woodhouse

As part of research for the exhibition a small group of volunteers worked in the uncatalogued Rockingham and Fitzwilliam family estate papers, now held in Sheffield City Archives, and made many fascinating finds including a most touching record of Stubbs’s presence at the house in a letter from Mary Bright to her husband Lord Rockingham: “Mr Stubbs arrived, but I was unable to determine what you meant him to do and tho’ I thought it was the Mare, yet without being certain, I thought it was a pity to bestow much upon so ugly a Lady upon her first good behaviour, God bless you my Dearest.”

Capturing such moments of unabashed human engagement, in the context of a heritage project, seems to go to the heart of both enlivening history and giving meaning to a historic site’s future, where so much of the work is done by a large team of dedicated volunteers.

By adapting an intelligent curatorial method, of mediating past through present, an approach tested last year by the Wentworth Woodhouse team with its local stakeholders, the preservation trust and team of curators and volunteers has set a template for building historically resonant, and informative exhibitions around the great pictures that once hung at the house and the neoclassical statuary that still has a place in it.

It demonstrates a constructive engagement with house, guides, researchers, and local community—Rotherham council has given handsomely to the restoration of the stables as part of the last government’s levelling up programme—one that offers a Wentworth Woodhouse template for a scholarly collaborative approach to saving and making creative use of a great historic building.

Stubbs and Wallinger: The Horse in Art, Tate Britain, London SW1, until 6 July 2025