Wornum’s diary: We are not amused?

Written during his tenure as keeper of the National Gallery between 1855 and his death in 1877, Ralph Nicholson Wornum’s diary—not an official document but “for my own use and ready information”—provides an engaging record of daily life at the gallery and is packed with information about pictures acquired for the collection, and their framing, restoration and display. There is much of human interest too within the diary’s pages, including references to gallery staff (deaths of colleagues are recorded respectfully within a black border) and visits by distinguished persons.

One such visit occurred on 17 February 1860, although not at the building designed by William Wilkins. Owing to lack of display space at Trafalgar Square, the gallery established an outpost at the South Kensington Museum (as the Victoria and Albert Museum was known until 1899) for its British pictures, which opened in December 1859. When Wornum showed Queen Victoria around the completed galleries, she remarked on “the excellence of the arrangement”, and he in turn “amused her by telling her some anecdotes about Turner”. These anecdotes, however, weren’t perhaps as amusing as Wornum thought, as Queen Victoria made no reference to them (or him) in her own journal entry for this visit.

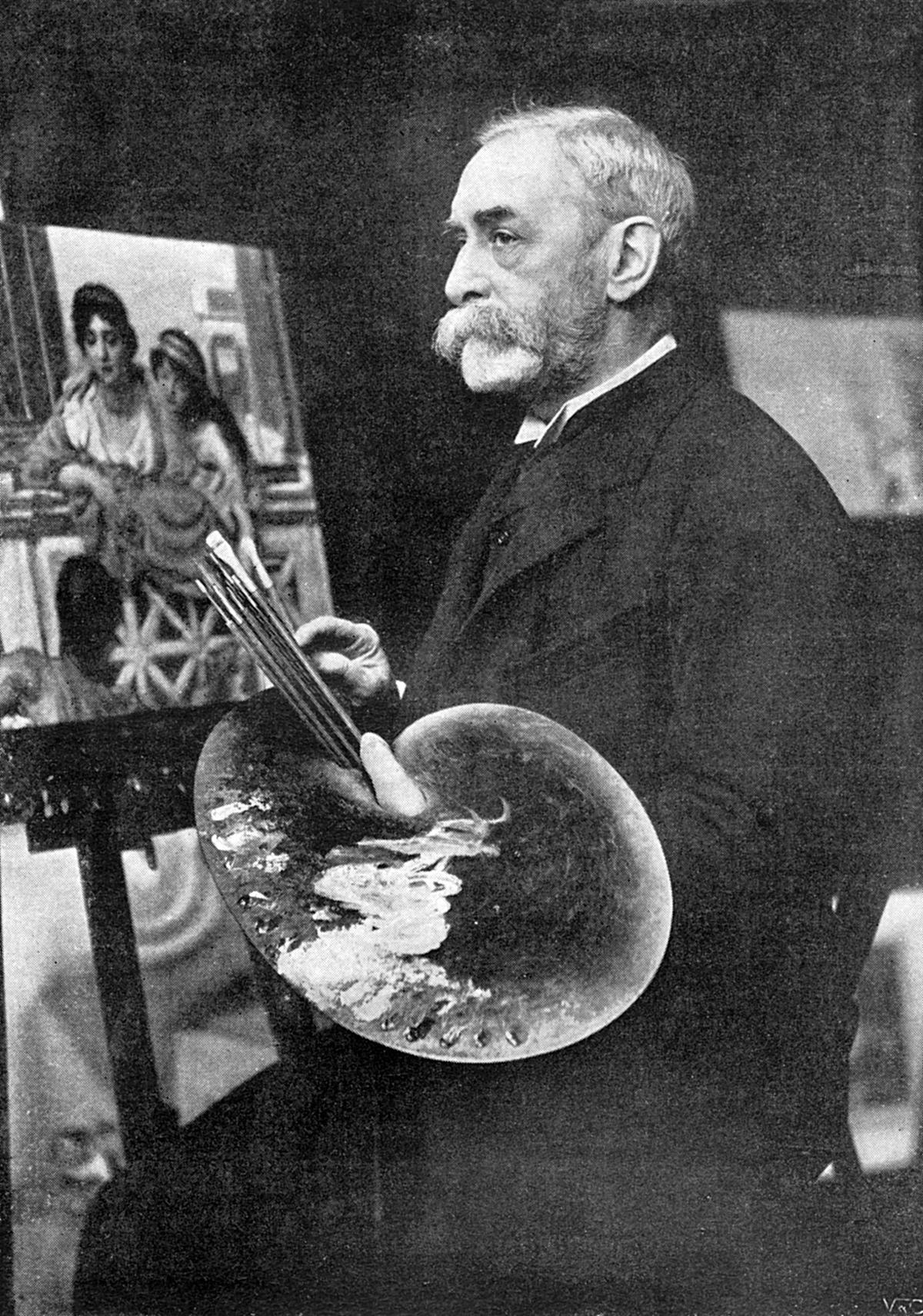

Poynter’s grand design on the Wallace Bequest

Following the death of Lady Wallace in 1897, the artist Edward Poynter, director of the National Gallery, lobbied for the transfer of the Wallace Bequest, with its matchless collection of French art and furniture, to Trafalgar Square. Writing to a Treasury civil servant on 25 February 1897, he argued that a new museum building (one of the options under consideration) would be a “useless extravagance” and recoiled at the prospect of “some hideous new block of buildings such as the modern architect thinks appropriate for a museum”. Instead, Poynter envisaged the Wallace Bequest housed in a “distinct building” on land then occupied by St George’s Barracks but physically connected to the National Gallery. An ambitious rehang would bring the gallery’s Dutch and French pictures into “historical series” with the Wallace Bequest. Poynter included in his letter a “very rough” sketch illustrating his vision of the layout.

In the event, the Lansdowne Committee, which had been established to determine the final arrangements for the housing of the Wallace Bequest, was unpersuaded by Poynter’s impassioned plea that by not moving it to Trafalgar Square, the committee (of which he was a member) would “miss an opportunity of making, perhaps, the finest gallery in Europe”.

The Wallace Bequest remained instead as a national collection, in a remodelled and enlarged version of Hertford House, the late Sir Richard and Lady Wallace’s stately house in Manchester Square.

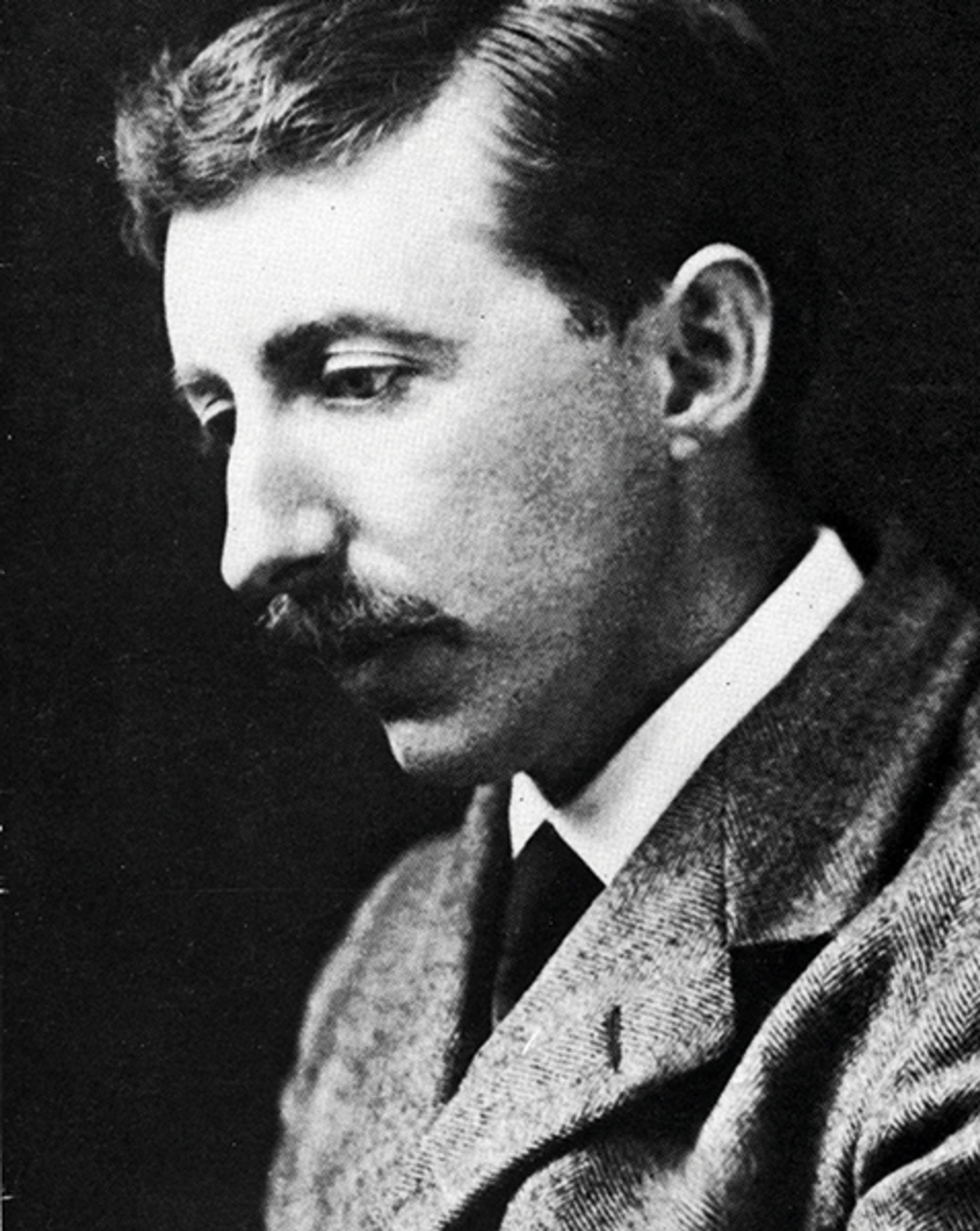

The novelist E.M. Forster worked as a clerk at the gallery in the 1910s Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

E.M. Forster, novelist, fire-watchman and picture cataloguer

Biographers of the novelist and critic Edward Morgan Forster (1879-1970) make only fleeting reference to his employment at the National Gallery as a part-time clerical assistant to the director, Charles Holroyd, making the monthly recurrence of his name in the petty cash book for 1912-18 especially striking.

From September 1914 to October 1915, Forster combined the roles of fire-watchman and “amateur catalogue-compiler”, although he seems to have been temperamentally unsuited to the latter. Forster was a frequent visitor to the gallery (he used it as the location for a chance encounter between Cecil Vyse and the Emerson family in his 1908 novel A Room with a View) and, during the Second World War, was an ardent supporter of the Picture of the Month initiative and the pianist Myra Hess’s highly popular lunchtime concert series. When it was announced that the latter was to end, he signed a petition (other signatories included the poet Louis MacNeice and the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams) urging its continuation beyond April 1946.