A plethora of valuable ancient manuscripts from the sealed Mogao Cave 17, also known as the Library Cave, located in a cave complex in western China, are due to go on display for the first time in 20 years in the exhibition A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang at the British Library in London next month. Items featured include the earliest examples of printed texts such as the Diamond Sutra, the world’s earliest dated, printed book, along with the Dunhuang star chart, the earliest known manuscript atlas of the night sky. These documents and objects throw light on religious and civic life in the town of Dunhuang in northwest China in the first millennium of the Common Era. Melodie Doumy, the lead curator of Chinese collections at the British Library, explains why this wealth of printed matter is significant.

The Art Newspaper: Why is the Library Cave considered one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the 20th century?

Melodie Doumy: The discovery of Mogao Library Cave, or Cave 17, near Dunhuang was a watershed moment in archaeology, leading some scholars to compare its significance to that of Tutankhamun’s Tomb. Found in 1900 by a Daoist priest Wang Yuanlu, the cave had been sealed for nearly 900 years and was filled with tens of thousands of manuscripts, printed documents and artefacts, dating from the fifth to the beginning of the 11th century.

These items encompass multiple languages, faiths and cultures. Many of the texts are unique copies or the only surviving examples of certain works, making them irreplaceable sources. The cave contained numerous Buddhist texts, including rare sutras, commentaries, and apocryphal works. These are crucial for understanding the spread and development of Buddhism across Asia, as well as the religious practices and beliefs of the time.

Moreover, the discovery included some of the earliest examples of printed texts, showcasing the advanced state of printing technology in China centuries before the invention of the Gutenberg press in Europe. Cave 17’s exquisitely handwritten or illustrated manuscripts, portable paintings and textiles also offer rare insights into the artistic achievements of the period.

The wealth of primary sources that have survived from this region gives us an unprecedented glimpse into the existence of the people that inhabited or transited through this Silk Road oasis, from merchants and Buddhist nuns, to diplomats and fortune-tellers and more.

Do we know why the cave was sealed up in the first place?

The exact reason remains a mystery, although several theories have been proposed and are still debated. Some scholars have argued that Mogao Cave 17 served as a repository for revered but damaged Buddhist manuscripts and items, considered as sacred waste, and that it was perhaps sealed in response to external threats. Others have proposed that the cave was used to hide materials from a monastic library in the early 11th century, in anticipation of an invasion either by the Tangut Empire or the Turkic Karakhanids. On the other hand, Cave 17 may simply have been walled over and painted as part of a wider renovation project during the 13th century.

A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang catalogue

Do the exhibition and catalogue reveal anything new about the Diamond Sutra, the world’s oldest dated printed book?

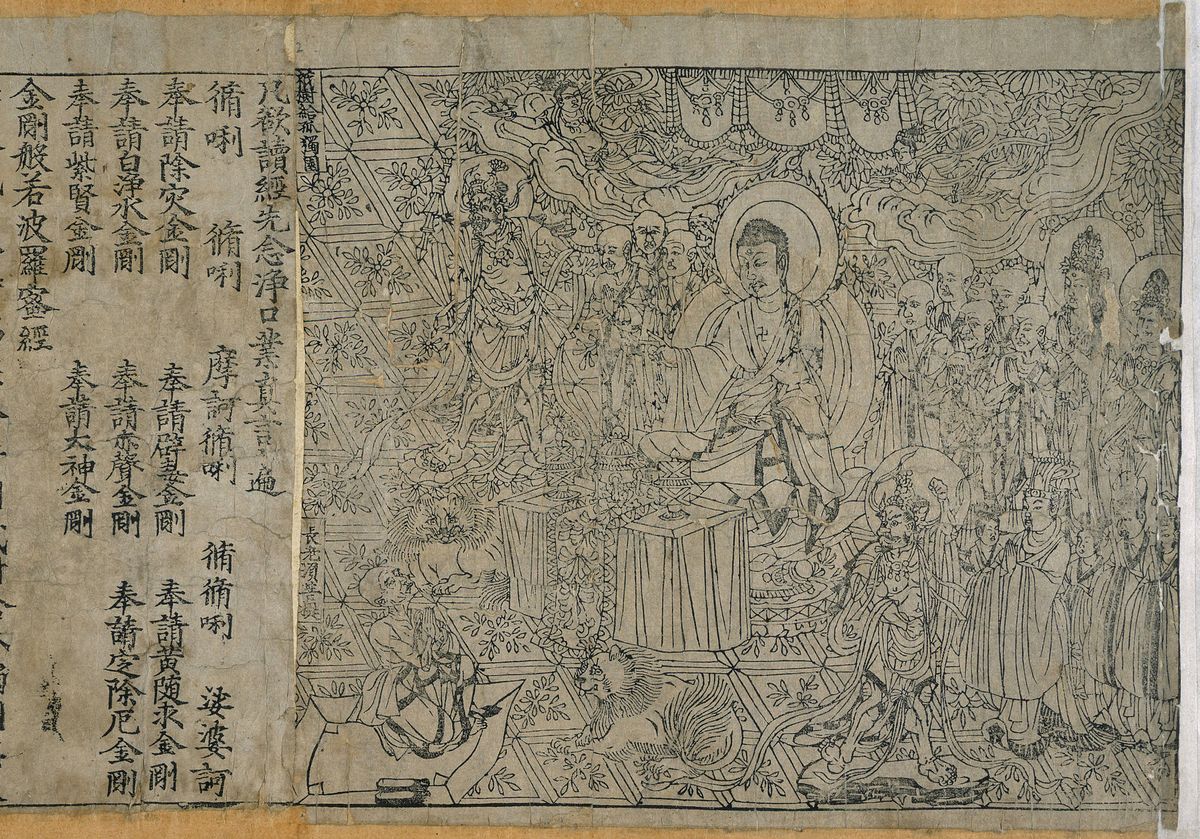

One of the most celebrated items from Cave 17 is a woodblock-printed copy of the Diamond Sutra, which bears the date 868CE. The colophon or dedicatory note at the end informs us that the scroll was commissioned by a certain Wang Jie on behalf of his parents and for universal distribution. The craftsmanship required for an item with such refined design, whose production relied on the collaboration of the most talented artist, calligrapher and woodcarver, attests to the significant advancement in printing technology. Scholars have thus suggested that the Diamond Sutra was probably made in Sichuan, one of the main printing centres at the time. The printed copy of the Diamond Sutra will be on display with two more printed items produced in Dunhuang, showing the spread of printing technology westwards along the Silk Roads. These important items are both linked to the woodcarver Lei Yanmei, establishing him as one of the earliest known woodcarvers and showing that his craftsmanship was acknowledged as an important part of the printing process.

How does the ongoing British Library digitisation project relate to the exhibition and catalogue?

In 1907, the British archaeologist Aurel Stein went to Dunhuang, where he acquired tens of thousands of manuscripts, paintings and other artefacts from the Library Cave. Today, many of the items that Stein purchased are cared for by the British Library, among other institutions. Stein’s visit to Dunhuang marked the beginning of the large-scale dispersal of Cave 17’s contents, which would be scattered across various private and public institutions, including in France, Japan and Russia, as well as the UK.

In 1993, curators and conservators from all the major institutions with holdings from Dunhuang and other Silk Road sites met at an international conference and agreed to work together to make these collections more accessible and to ensure their long-term preservation. In 1994, the British Library established the International Dunhuang Programme (IDP) to coordinate this collaboration. [This year] marks the 30th anniversary of this pioneering global partnership, which continues to bring together online the eastern Silk Road collections of more than 35 institutions, including the Dunhuang Academy, the National Library of China, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Ryukoku University in Kyoto. The IDP keeps evolving and responding to the needs of researchers, professionals and the wider public.

Both the exhibition and catalogue will include details about the IDP’s efforts in the last three decades. We hope that this will help raise awareness about its mission to work collaboratively to provide high-resolution images, contextual information and learning resources via the IDP website, promoting the understanding of the history and cultures of the region.

• Melodie Doumy, A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang, British Library Publishing, 112pp, 12.99 (pb)

• A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang, British Library, London, 27 September-23 February 2025