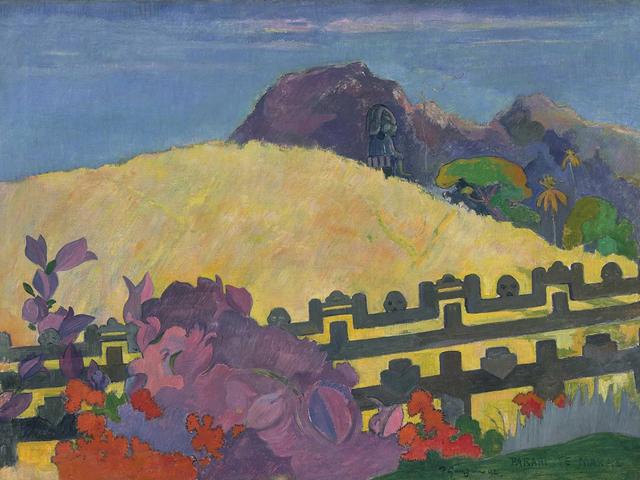

The National Gallery of Australia (NGA) has trumpeted its status as the country’s first public collection to own a major painting by Paul Gauguin, after it paid US$6.5m for The blue roof or Farm at Le Pouldu (1890).

The painting was acquired from an international private collector. That was presumably the same collector who paid US$5.3m for the painting through Christie’s in 2000.

Before that, The blue roof or Farm at Le Pouldu was in the collection of Wendy and Emery Reves. Born in Hungary in 1904, Emery Reves immigrated to Paris and became a writer and editor. He was press agent and close friend to Winston Churchill. His American-born wife was a model.

The Reves’ resided on the French Riviera in a palatial villa where Coco Chanel once lived.

The blue roof or Farm at Le Pouldu has been on view at the NGA since the gallery opened its major exhibition, Gauguin’s World: Tōna Iho, Tōna Ao (until 6 October), in June. The exhibition was curated by the former Louvre director, Henri Loyrette.

The purchase of the work was announced only on 1 August.

“The newly acquired painting is a key example from his Brittany period,” the National Gallery said in a statement. “Following the exhibition, the work will join the permanent collection displays of the National Gallery to be appreciated by audiences for generations to come.”

The NGA organised a Gauguin symposium to celebrate the opening of Gauguin’s World: Tōna Iho, Tōna Ao, at which a number of Polynesian scholars spoke alongside Loyrette.

The former director of the Musée de Tahiti et des Îles, Miriama Bono, said Gauguin was a “stranger” to Tahitians who knew the artist only through postcards and tourist tat. Not one of his paintings could be seen in French Polynesia, although he lived there for years and died there in 1903.

Bono said contemporary Polynesian artists were now addressing Gauguin’s fraught legacy, often using humour and adopting elements of Gauguin’s work into their own. She said there was “an artistic wealth waiting to blossom in the Pacific”.

Bono hinted at the impatience local people feel when subjected to questions about the clichés of Gauguin’s colonialist seductions of very young local women.

“We are always asked this question in Tahiti, especially as a woman, and we would love that we were asked some other questions,” Bono said. “Of course we are not happy with [the way Gauguin cut a libidinous swathe through Polynesia], but we have [many other] things to say.”