There were no dress rehearsals and no dance steps required of the volunteers who performed the artist Rasheed Araeen’s “ballet on water” Discosailing in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in east London last weekend. “Curious and willing” were the main criteria listed on the open call launched by The Line outdoor sculpture trail, which staged the work’s UK premiere to coincide with the start of the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris.

Nine at a time, the participants donned billowing yellow capes (the sails) and stepped out onto red circular paddle boards (the discs) that floated down the Waterworks River for six half-hour performances on 27 July. But with no paddles to steer, they had to trust in the real choreographers of the event—the wind and the water.

Performers in Discosailing: A Ballet on Water by Rasheed Araeen at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, part of the summer programme by east London’s public art trail, The Line Stephen Chung/PinPep

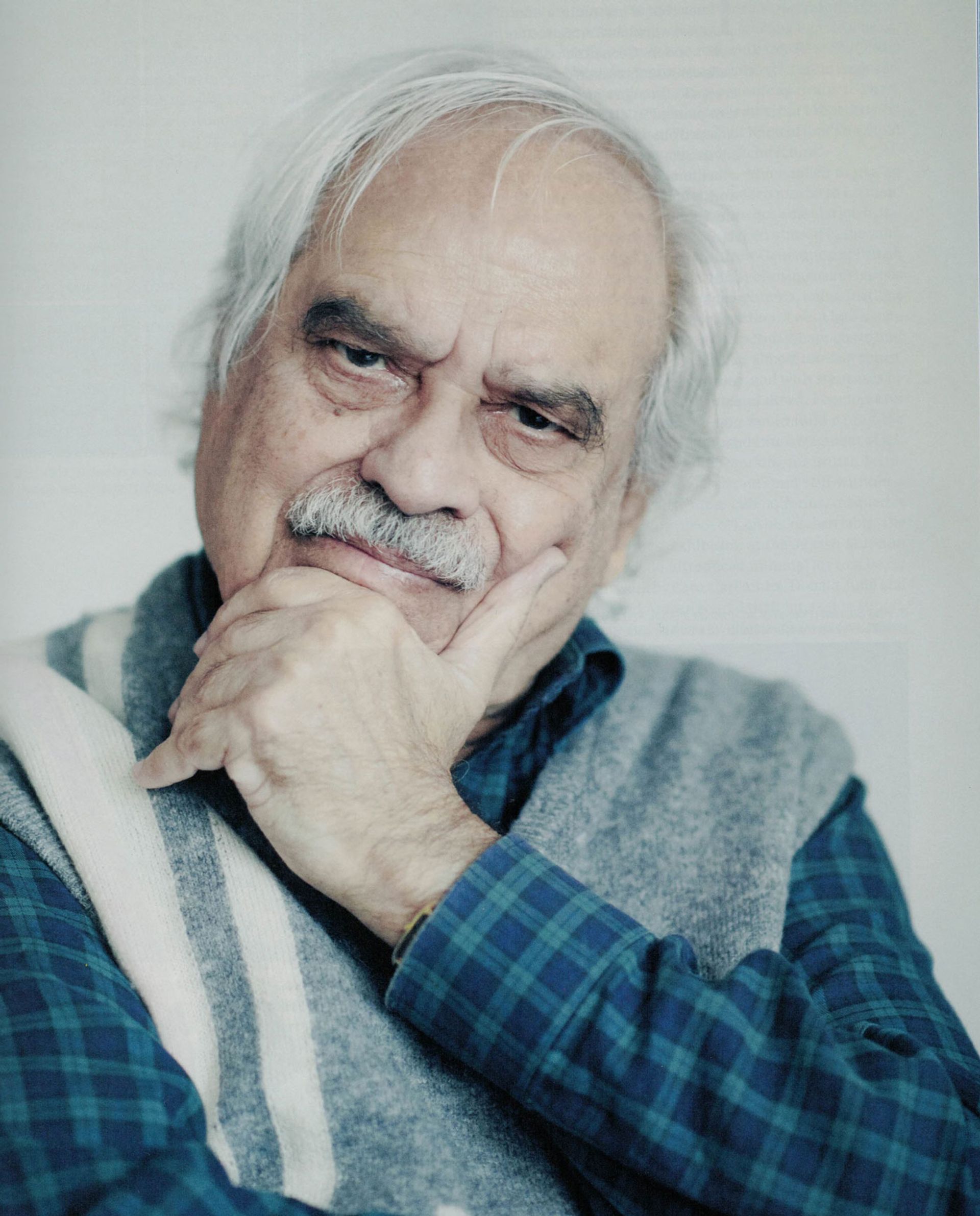

At the age of 89, Araeen himself was not performing but was among the audience who gathered on a bridge to watch the unpredictable spectacle unfold on a sunny London afternoon. More than 50 years have passed since the idea for Discosailing first came to the Pakistani-born artist in 1970, as he invited members of the public to launch his floating polystyrene sculptures, Chakras, into a canal in Hammersmith, west London.

“It was a sort of festival there, and many people were doing their things. A couple was sitting on a polystyrene slab and floating around on water. While watching this it occurred to me, suddenly, as a brainwave, that I could make people float on my discs,” the artist tells The Art Newspaper.

Known for both his pioneering contributions to minimalist sculpture in the UK and trenchant activism against racism in the British art establishment, Araeen worked on Discosailing for several years in the early 70s before it was “put to rest”. For decades it existed as a conceptual project, archiving his “drawings, photos of my posing, in the way the person on a disc would do, at the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens, and so on”. The documentation is now part of the collection of the Sharjah Art Foundation, along with a prototype disc Araeen had fabricated in 2001 by marine specialists at the University of Plymouth.

Rasheed Araeen: “Discosailing, performed individually or collectively involving many performers, may appear as a sport but its underlying conception is the idea of a floating sculpture or sculptures" Photo: Benjamin McMahon

Discosailing has made the leap from concept to live public performance only once before. The artist credits his friend and associate, Peter Fillingham, with the “great success” of a 2019 staging on a pond in Moscow’s Gorky Park during his retrospective at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art.

It was a film of that “extraordinary” event that captured the imagination of Megan Piper, the co-founder and director of The Line, when she visited Araeen’s north London studio last year. “As The Line’s programme has expanded to include performance and the connection to water being central to our work, it felt like a perfect opportunity to realise it with him,” she says. The project, co-curated with Arup Phase 2, the cultural arm of the engineering firm Arup, anticipates a new sculpture commission by Araeen that will join The Line’s waterside art trail between Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park and Greenwich Peninsula.

The timing with the Paris Olympics felt apt, not only because The Line is itself part of the urban regeneration legacy of the 2012 Olympics in London. Araeen envisioned Discosailing as a kind of “counter to the idea of competitive sport”, Piper says—a way of unifying people in a shared physical activity that challenged what he saw as the aggression, voyeurism and consumption of the body in sports.

Performers in Discosailing: A Ballet on Water by Rasheed Araeen at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, part of the summer programme by east London’s public art trail, The Line Stephen Chung/PinPep

“Discosailing, performed individually or collectively involving many performers, may appear as a sport but its underlying conception is the idea of a floating sculpture or sculptures,” the artist wrote in his 2010 book Art Beyond Art—Ecoaesthetics: A Manifesto for the 21st Century. “The human body, sails and the disc form an integral system in which there is no separation between the sailing craft and the disco-sailor.”

But at least for some of Saturday’s participants, finding their feet on a floating disc was not smooth sailing. Onlookers cheered as one especially tall performer finally stood upright after three courageous attempts pitched him into the water. Some played it safer by sitting cross-legged or lying down, and were buffeted to the river bank. Only a few poised disco-sailors stretched out their arms and caught enough momentum in their sails to surf under the bridge and be towed back upriver for a second try.

In opposition to sports, Araeen hoped to create a meditative exploration of movement, closer to ballet or tai chi, that would also be a collective action, relying on collaboration instead of competition. Discosailing aspired to “challenge what the self-centred narcissistic body produces as a work of art, and to offer an alternative to what is trapped in a decaying and decadent consumer culture,” he wrote. “This alternative is for an optimistic and affirmative future based on harmonious relationships not only between human beings but also with natural forces such as water and wind.”

Rasheed Araeen, Discosailing sketch, watercolour on paper, 2002. Printed in the artist's Art Beyond Art (2010)

Piper pays tribute to Araeen’s reversal of the tradition of “sculpture as the static object” and the “powerful idea” to activate his work by inviting in the public as well as the elements, dismantling the boundaries between art and everyday life. “Sculpture is brought to life through that activation.”

Any curious readers willing to become part of Araeen’s playful living sculpture will have a second chance on 27 September, when Discosailing will be performed again in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park during London Sculpture Week. Individuals and groups are welcome to sign up online.

Asked whether he felt the meaning of the work had evolved over the half-century since it was conceived, Araeen says: “The meaning of the work now hasn’t changed; it’s now confirmed not only its practicality but also its significance, by the performers themselves.”