Archaeologists in Saudi Arabia have discovered rare ancient rock art at the entrance to a remote desert lava tube—a cave formed by flowing lava. Located in the volcanic field of Harrat Khaybar, around 125km north of Medina, the art was found near Umm Jirsan, another lava tube where the team identified evidence for at least 7,000 years of repeated human occupation.

“We found the first documented evidence that people occupied these lava tubes,” says Mathew Stewart of Griffith University in Australia, the lead author of the research paper on the discovery, published in the journal Plos One. “This included lithic artefacts made of obsidian, basalt and chert, as well as various stone structures and rock art.”

Organic remains rarely survive in Arabia’s harsh desert climate, making it difficult to find evidence for early human activity. Consequently, the team decided to investigate caves and lava tubes to see what might be preserved in these protected underground environments. While exploring Umm Jirsan—the longest lava tube in Arabia—they found the skeletal remains of domesticated sheep and goats among the artefacts. “Dating of the material tells us that use of the lava tube started by at least the Neolithic and persisted for millennia,” Stewart says. “These findings add to the broader work in the region, which is documenting a rich and dynamic archaeological landscape of the area during the Holocene.”

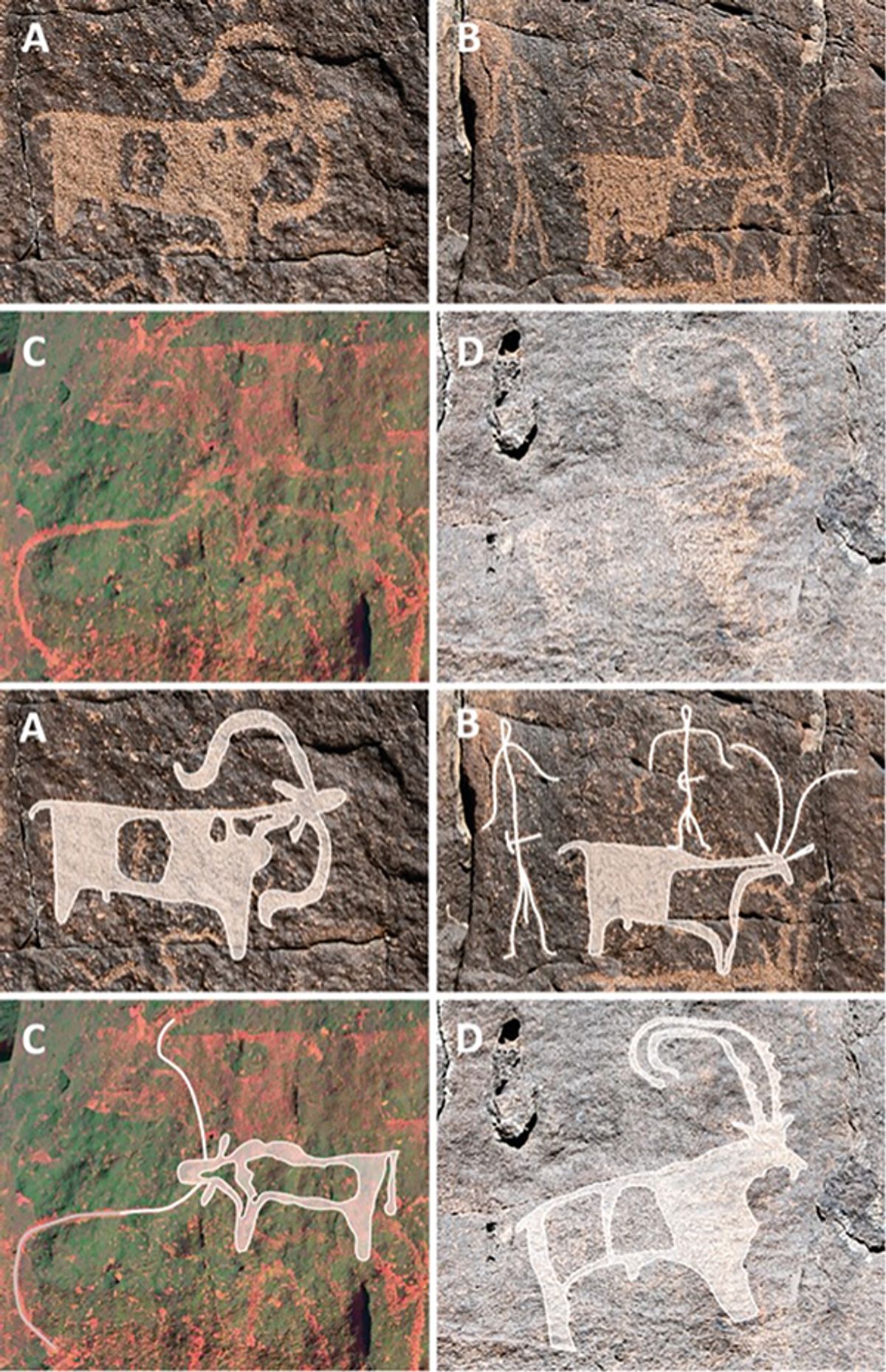

While surveying the collapsed entrance to a lava tube 1.3km east of Umm Jirsan, the team discovered 16 rock art panels, which were pecked into the rock with a tool, probably around 5,000 to 7,000 years ago. These are the only known examples of rock art in the area, and show sheep and goats—rare in northern Arabian rock art—as well as long-horned cattle, possibly ibex, and human stick figures with tools on their belts. The panels bear at least six herding scenes—again, rare in the region—one of which shows dogs herding goats and sheep. Some figures overlap others, indicating different phases of production.

“The depiction of sheep is rare in the rock art in other nearby areas of Arabia, as shown by our earlier research,” Stewart says. “This suggests that these livestock may have been particularly important to the people inhabiting the area of the Harrat Khaybar. That there are depositions of herding scenes tells us that pastoralists visited the cave, perhaps utilising it as a place of refuge and a source of water.”

Based on the team’s research, it appears that people did not live permanently in the Umm Jirsan lava tube, but used it as a place to rest while travelling between oases with their livestock. These pastoralists may also have hunted gazelle and ibex, and perhaps used the lava tube as a water reservoir.

“This opens up an exciting new avenue of research in Arabia, one focusing on underground settings where the preservation of organic materials like bone is much better than at more surficial sites,” Stewart says.