Images of Black male bodies, posing or in repose, acrobatic or monumental, unfurl in saturated hues across the walls of Victoria Miro’s galleries. Painted by the Trinidadian brothers Boscoe and Geoffrey Holder, mostly during the past two decades of the 20th century, they display an unabashed eye for beauty. Their curation shows a similarly bold appreciation for the contemporary cultural moment.

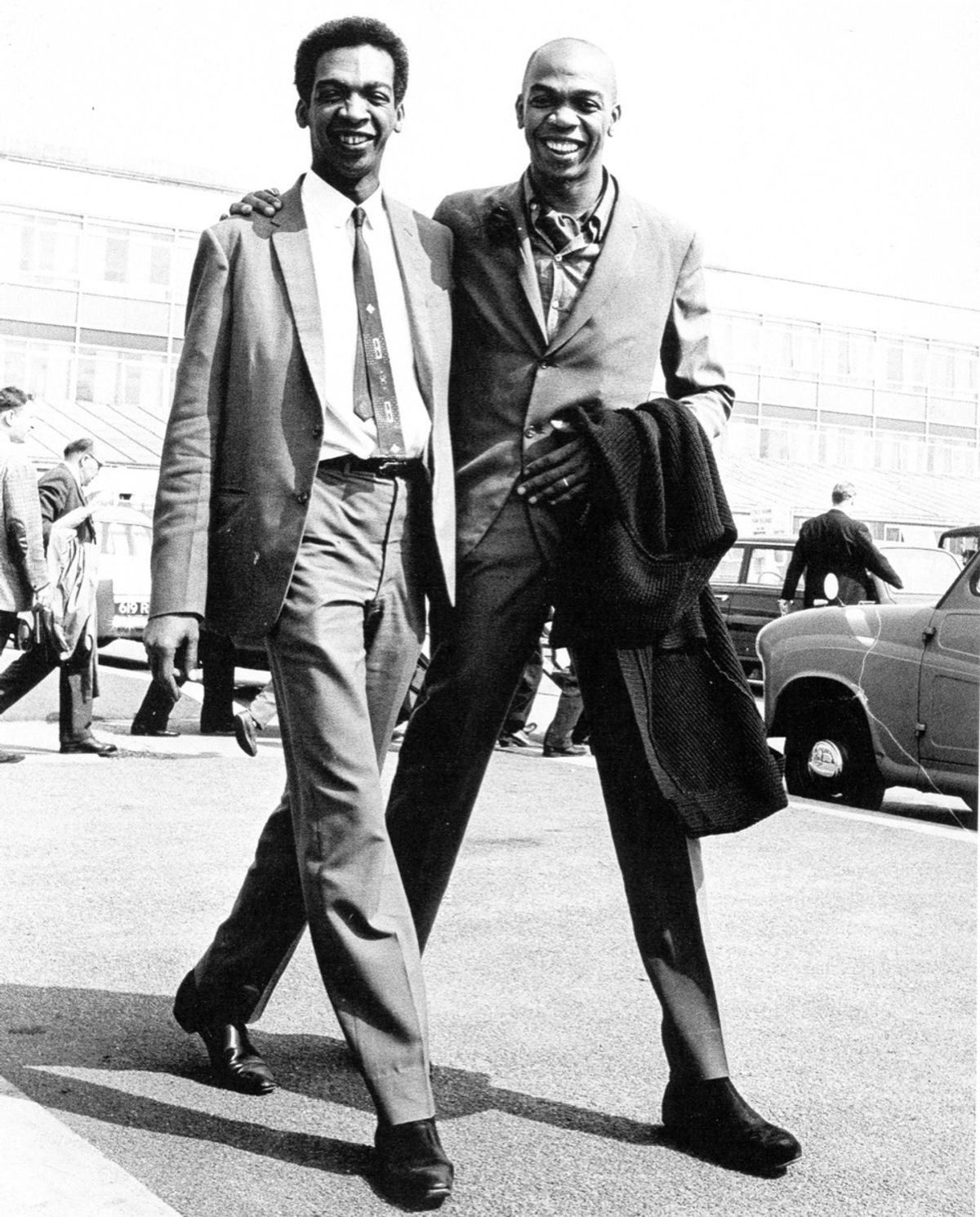

Few exhibitions are accompanied by back stories as compelling as the biographies of the Holder brothers. Boscoe (1921-2007) was a piano prodigy at the age of six, and also sketched regularly. “In Trinidad you are supposed to play cricket and box, but he was drawing nudes in the back of his exercise book,” the artist’s son, Christian Holder, says.

Later, still in Trinidad, Boscoe set up a dance company. However, in his early 20s he experienced a nervous breakdown because, his son explains, “there were always impediments placed in his path because of his race”. Boscoe recovered and, in 1950, moved to London where he set up a new dance company, Boscoe Holder and his Caribbean Dancers.

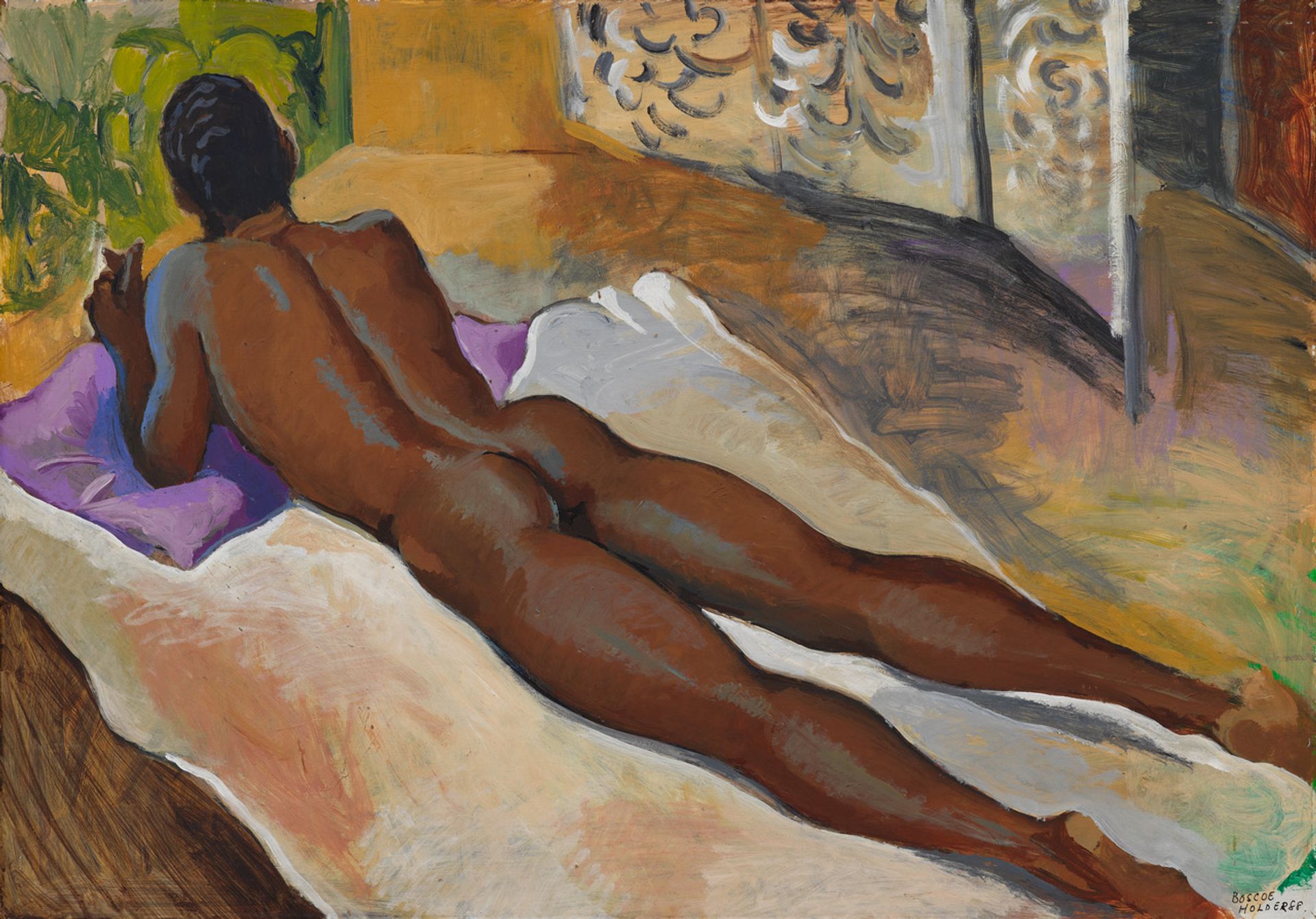

Boscoe Holder, Fret Work (1988) © Boscoe Holder. Courtesy of the Boscoe Holder Estate and Victoria Miro

Dancing skills open doors

In the UK capital his skills as a dancer were a passport into the higher echelons of the theatre world—the circles of the designer Oliver Messel, the actor John Gielgud and the playwright Noel Coward. “In those days, quite often, you’d meet people and they’d let you know how they felt: ‘I like you, but I don’t like them’ sort of stuff. But that was fine, you just got on with it. London was wonderful,” Christian says.

Elsewhere, Boscoe’s brother, eight years his junior, experienced a parallel success. Geoffrey Holder (1930-2014) mounted his first exhibition in Trinidad when he was just 14 years old. He performed in his older brother’s dance company when he was eight and, after Boscoe left for London, took it over. In 1952, he financed his move to New York with the sales of his paintings.

There, Geoffrey fell in with the legendary choreographers Martha Graham, Alvin Ailey and Arthur Mitchell. He was a principal dancer at the Metropolitan Opera Ballet in the 1950s, designed a ballet about the Haitian painter Hector Hyppolite in the 1960s, and in the 1970s won Tony awards for his direction and costume design for the Broadway musical The Wiz. He was also the face of the soft drink 7-Up throughout the 70s and 80s, and played the Bond villain Baron Samedi in the 1973 film Live and Let Die.

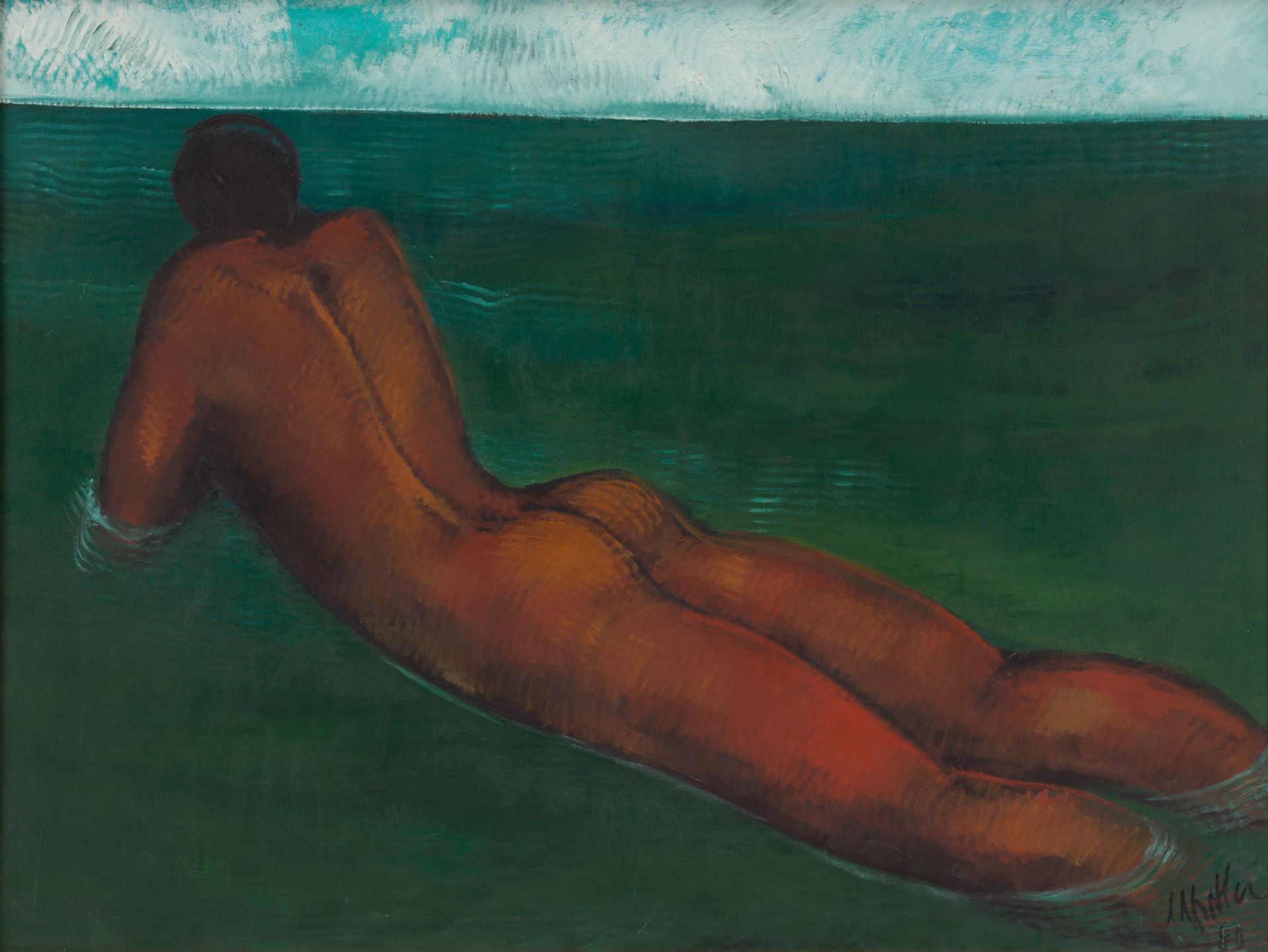

Geoffrey Holder, Swimmer (1980) © Geoffrey Holder. Courtesy the Geoffrey Holder Estate and James Fuentes

Despite their matching triumphs, the brothers’ styles diverge neatly. Boscoe paints naturalistic figures in informal situations—on the beach in a swimming costume, or sitting on chairs at home. Geoffrey, meanwhile, worked his subjects into symbols—a broad-shouldered man carrying a woman on his back, or the bodies of a couple entwined, cropped so their heads disappear from the frame.

“Being a painter is at the centre of how he was able to make his statement,” Geoffrey’s son Leo says. “It wasn’t just about dance, he did sets, music, costumes, it was all one thing—all his ballets are extensions of his paintings.”

The fine art practices of both Holder brothers have long been overshadowed by their celebrity status in the fields of dance and performance. Now, however, in an time when the conventional hierarchies between art forms are out of favour, descendants, dealers and scholars are seeking recognition for the pair as significant painters in their own right.

• Boscoe Holder | Geoffrey Holder, Victoria Miro, London until 27 July