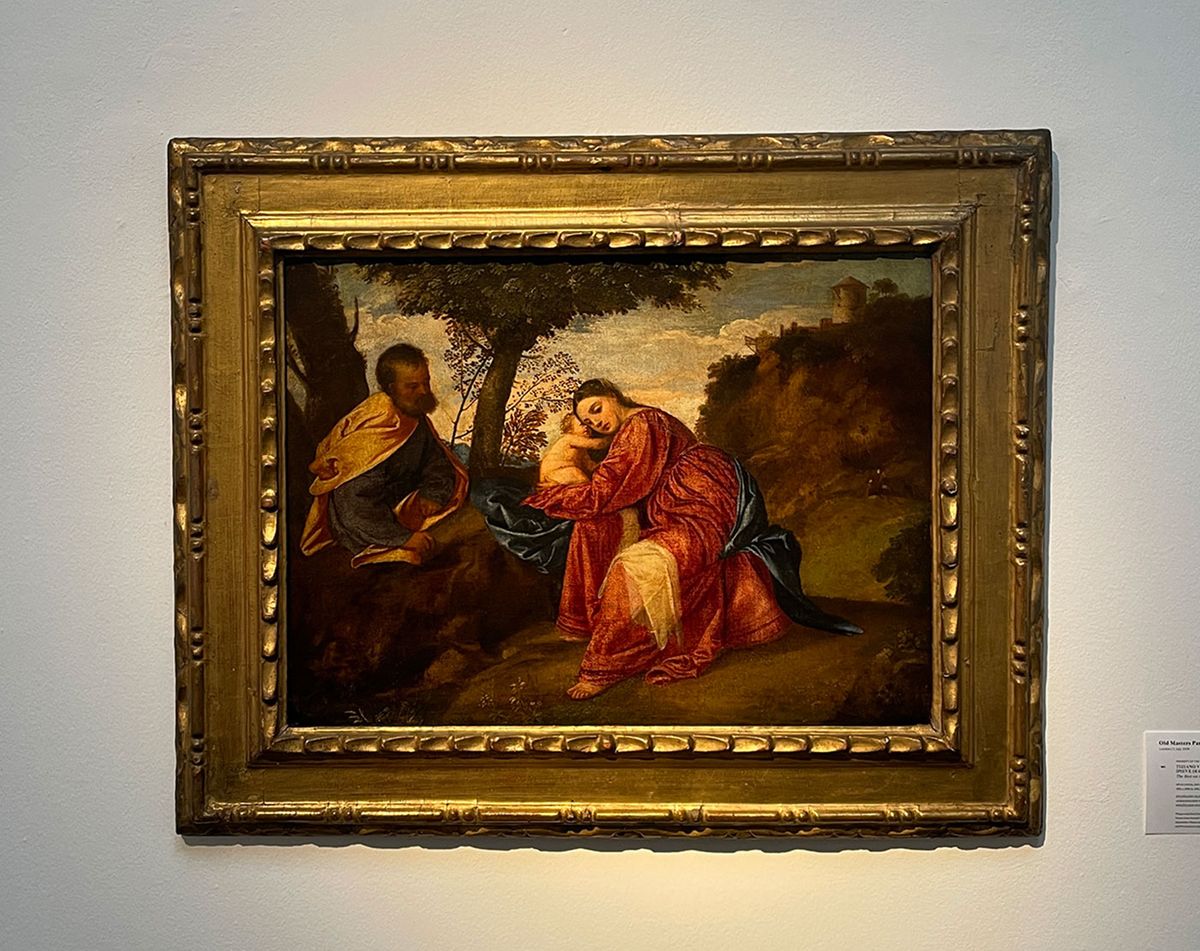

The bus-stop Titian. It hardly has the same ring about it as The Longleat Titian, which Christie’s would rather we call it. But, perhaps inevitably, the sensational story of the theft, 29 years ago, of Titian’s The Rest on the Flight into Egypt (1508-10), and its later reappearance at a London bus shelter, has dominated the headlines as the auction house prepares to sell this exquisite early painting by the Venetian master, made at a pivotal moment in Titian’s career and in the history of the Renaissance.

The heist story has a glorious narrative arc: just after 9pm on 6 January 1995, professional thieves used a ladder to climb up to a window of the State Drawing Room at Longleat House, in Wiltshire, south-west England. The 7th Marquess of Bath, the owner of this masterpiece of Elizabethan architecture, was dining in rooms above and heard nothing as the window was smashed and burglars broke in and quickly escaped with the Titian—which the marquess described as "the jewel of my collection"—and two less important works. The burglars were long gone when police, alerted by automatic alarms, arrived after 14 minutes.

Seven years later, following the announcement of a £100,000 reward, the painting was recovered, unframed, in a bag—a checked nylon zip-up, the kind often used for laundry—at a bus-stop in Richmond, south-west London, and the painting was returned to Longleat. But now the present marquess has decided to sell it. Its estimate is £15m-£25m.

An eventful early history

The painting's wider history is hardly less eventful, and undoubtedly feeds into its value. “It's exceptional to have this unbroken, documented provenance, all these incredible collections,” says Letizia Treves, the global head of research and expertise at Christie’s. It first appears in documentation in the collection of a Venetian spice merchant, Bartolomeo della Nave, whose collection of Venetian Renaissance masterpieces included some 15 Titians spanning his career, from the Longleat picture to the Death of Actaeon, one of the great poesie, made in the 1570s. “It was one of the top three collections to see in Venice,” Treves says.

When Della Nave died in 1632, the collection was sold, almost in its entirety, to James, 3rd Marquess of Hamilton (later 1st Duke of Hamilton), but sold again soon after because Hamilton was executed by the English Parliament for high treason in 1649 a few weeks after the execution of King Charles I. It was then bought, similarly en bloc, by the Habsburg Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria. His collection was memorably captured by David Teniers in a series of Kunstkammer pictures. One, in the Prado, includes The Rest on the Flight to Egypt at its centre, directly above the archduke. The Titian was among the works later looted by Napoleon’s troops and taken to Paris before returning to Vienna in 1815. Most of the collection now forms the basis of the Kunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna. But The Rest was separated off.

It was next sold, probably in the 1840s, to Hugh Andrew Johnstone Munro, a friend and patron of J.M.W. Turner who, rather neatly, paid for Turner’s 1833 trip to Venice—the English painter had an ardent regard for Titian’s art. After Munro’s death, it finally found its way to Longleat, being acquired by Colnaghi at Christie’s in 1878 for 350 guineas (about £35,000 today), almost certainly on behalf of the 4th Marquess of Bath. It was then taken to the Longleat State Drawing Room where it remained until that fateful night in 1995.

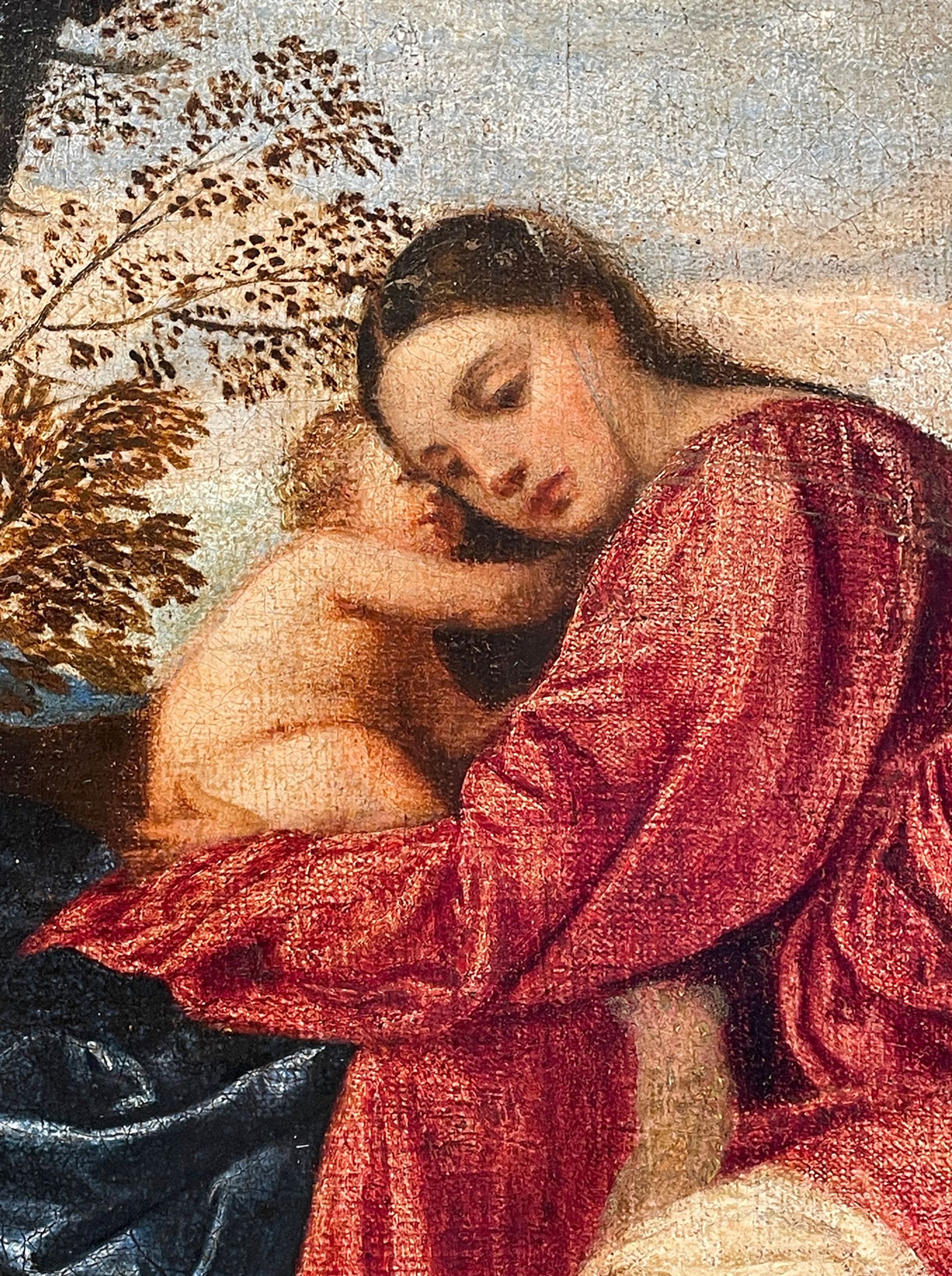

"There is something deeply Giorgionesque in the landscape and in the relationship between the figures, the ground and the flowers.” Detail from Titian's The Rest on The Flight into Egypt The Art Newspaper, courtesy of Christie's

That the 7th Marquess of Bath used the term “jewel” is appropriate. Painted on canvas later affixed to panel (which helped keep it safe through the theft-and-plastic-bag ordeal), The Rest is modest in scale: “it feels private, very domestic, a bedroom picture”, Treves says. Titian’s birth date remains unknown, but scholars agree it was probably between 1488 and 1490, so he was in his late teens or early 20s when he made The Rest. He had been in Bellini’s studio since shortly after he moved to Venice as a boy from his Dolomites birthplace, Pieve di Cadore. He was also in the circle of Giorgione, another Bellini disciple, who was a decade or so older and whose influence is palpable in the picture. “It was never believed to be by Giorgione,” says Antonio Mazzotta, a Titian specialist at the University of Milan, “but there is something deeply Giorgionesque in the landscape and in the relationship between the figures, the ground and the flowers.”

The influence of Bellini and Giorgione

Treves argues that distinct parts of the composition evoke the influence of these two masters. The head of Joseph is “the most Bellinesque” element; “beautifully preserved”, she says, with “soft, sensitive rendering of the fluffy beard and the slightly aged dark skin”. But, she adds, “the flavour of this picture is predominantly Giorgionesque, because of this pastoral landscape, that’s the most prevalent influence.”

Other artists are implicitly present. As Mazzotta has written, Giorgione’s concepts of landscape were developed in part through his meeting with Leonardo da Vinci, who had visited Venice in 1500 seeking refuge after the French invasion of Milan. Albrecht Dürer, meanwhile, had visited Bellini’s studio on a long stay in Venice between 1505 and 1507, and was hugely influential on depictions of nature in Venetian painting after that date.

“This monumental body of the Virgin would have been inconceivable just five years earlier." Detail from Titian's The Rest on The Flight into Egypt The Art Newspaper, courtesy of Christie's

What makes The Rest distinctively Titian, then? “I think the Madonna in particular,” Treves says. The Virgin has “such a presence and the monumentality of that Madonna and Child, the way she's enclosing [Christ] as well. She's really quite a solid figure.” In this, too, Titian was reinterpreting important influences, Mazzotta suggests. Last year, he curated the exhibition Tiziano 1508 for the Galleria dell’Accademia in Venice. “One of the main arguments was that the arrival of Michelangelo's ideas in Venice through the copies of the Battle of Cascina cartoon was a key ingredient for this new attention towards the monumental body—which could have been male or female—in about 1508.” Among the most prominent manifestations were the pivotal, but now mostly lost, frescoes done in that year by Giorgione and Titian at the Fondaco dei Tedeschi on the Grand Canal. The pose of Titian’s Judith, which is known from a fresco fragment that is now in the Galleria Franchetti in Venice, relates closely to that of the Virgin in The Rest. “This new Michelangelesque ingredient in an environment that was already so stimulated by Giorgione's art, by Dürer, who had just been in Venice, was the final ingredient that Titian was able to mix with the others,” Mazzotta says. “This monumental body of the Virgin would have been inconceivable just five years earlier.”

But allied to the weight of the figure is her poetry, what Treves describes as the “pensive look on her face”, and a “very natural interplay between mother and child”, typical of Titian’s grasp of intimacy, whatever his subject. Christ appears to be playing with his mother’s hair. “To me it looks like he's sort of tugging it and she's sort of pulling towards him,” Treves says. “And the cloth on her knee to me looks like it's almost like either her muslin that she's nursed him in, or a swaddling cloth that he's just been freed from, wriggling in her arms.”

A particularly “eloquent” Titianesque facial type. Detail from Titian's The Rest on The Flight into Egypt The Art Newspaper, courtesy of Christie's

Mazzotta argues that the Madonna possesses a particularly “eloquent” Titianesque facial type, echoed in other depictions of the Virgin over more than a decade. So was Titian using a particular, favourite model? “It's hard to tell without documents or descriptions about how they really worked, but there must have been a model, or just an idealised facial type that Titian pursued for several years, with this very high bridge of the nose.”

Then, there is the sheer gorgeousness of the hues. “Colour is so important to Titian,” Treves says. “The whole composition is built around the primary colours that dominate, particularly the red lake.” She also praises Titian’s characteristic use of complementary tones. Joseph’s yellow cloak is set against an undergown of lilac blue. “These are staple colours in early Titian.”

A painting that packs an enormous punch

Aside from the sheer rarity of a painting from this period coming to market, how can we assess its status in his vast oeuvre, with so many landmark works? Mazzotta has no doubt about its importance. “Maybe I'm emotionally attached to it, but it is a little masterpiece,” he says. “It's a cabinet picture rather than a portego picture [a large, salon work] or an altarpiece. But it doesn't mean that Titian didn't put in the same effort. It doesn't mean that it doesn't contain enough ingredients of genius.”

Indeed, hung at Christie’s in King Street, in London, it packs an enormous punch, belying its size: “it has real wall power”, as Treves puts it.

And once sold at Christie’s, it may be destined for a wall that is not public. It may only rarely, if ever, be visible to us again, and certainly never at a bus-stop. See this beautiful picture if you can.

UPDATE 2 July: Titian's The Rest on the Flight into Egypt sold for £17.6m (with fees) at Christie’s Old Masters Part I sale on 2 July