The artist Pavlo Makov, who represented Ukraine at the 2022 Venice Biennale, is based in Kharkiv, a city in northeast Ukraine that according to news reports is now facing a “barrage of attacks”. Over Zoom, he describes his experience of living and working in Ukraine’s second largest city.

St Petersburg-born Makov notes that, at the time of writing, Russian forces are massed around 24km from Kharkiv. He said that supermarkets close when the war sirens sound and that occasionally the bombing makes the windows in his studio shake. “Human beings are so [resilient] they can get used to everything,” he says. “Let me be clear—there is no panic in the city.” He adds: “Anything can happen when you deal with Russia… For me, it's absolutely clear that they can use also nuclear weapons.”

Makov stresses that there is an active artists’ community in Kharkiv, pointing to his own solo show at Kharkiv National University, which includes The Fountain of Exhaustion, his installation first seen at the Venice Biennale two years ago. Getting the work to Venice was challenging. “It was difficult to take the fountain to Venice; in 2022 [the co-curator] Maria Lanko called me in the bomb shelter in Kharkiv from Vienna. We managed to rebuild the fountain for the Venice Biennale and made it in three weeks in Italy.”

He adds: “I have a big exhibition at the Yermilov art centre [until 29 June]. Yermilov is the very famous Constructivist artist who lived, worked and died in Kharkiv. [Yermilov] is a contemporary centre that belongs to the Kharkiv University, which decided to restart artistic activity more than a year ago.”

Another version of The Fountain of Exhaustion is on show in the Museumsplatz in Vienna, after the MuseumsQuartier curatorial team there invited Makov to present the piece in the Austrian capital. The project was almost jeopardised after he turned down sponsorship from the Austrian bank Raiffeisen last year, due to its continued operations in Russia. (Other funding was secured).

It also concerns Makov that as the war progresses “there is absolutely no idea about [how to manage] the cultural policy and representation of Ukraine as a cultural state—there is absolutely no idea how to present Ukraine as a cultural society”. Most Ukrainian cultural initiatives launched outside of the country are now funded by private sources, he says. “Everything we did in Venice was through sponsorship.”

He says that private collectors continue to buy his works, which means he can continue to make a living. “I have very good relations with Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza, who bought three of my works last year. The Victoria and Albert Museum [in London] also bought two works from me.” He also had the opportunity to move to Italy but says he would rather stay in Ukraine. “When I realised that I [would be] staying further away from Ukraine, I felt I was simply losing my senses,” he says.

Thyssen-Bornemisza has been instrumental in keeping Ukrainian artists in the spotlight in the wake of the invasion through her initiative Museums for Ukraine, which, says a spokesperson, aims to “protect, preserve and celebrate the cultural objects and collections of Ukraine”.

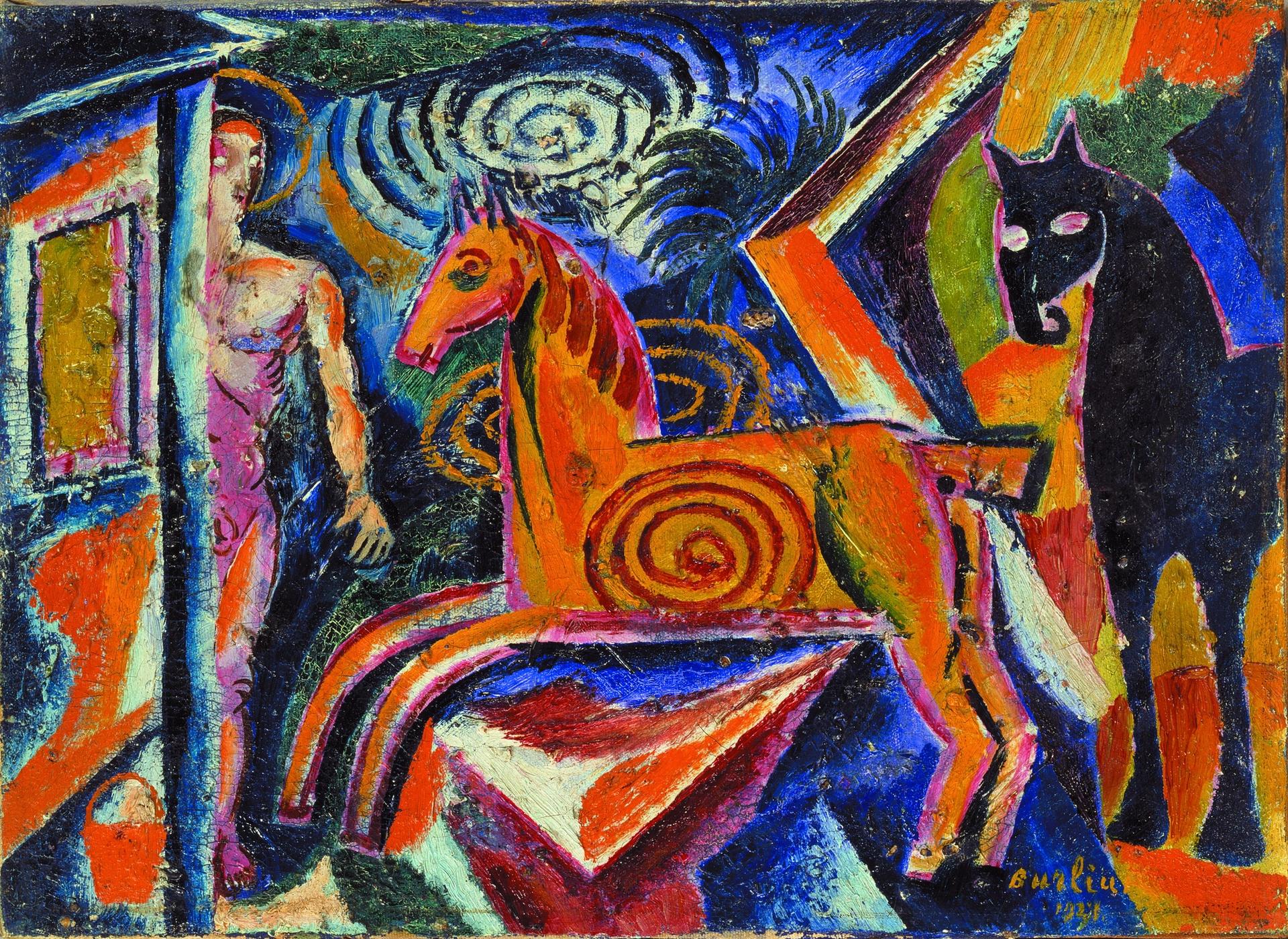

Davyd Burliuk, Carousel (1921), one of the works included in the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s, opening at the Royal Academy of Arts in London this week

National Art Museum of Ukraine © The Burliuk Foundation

Museums for Ukraine is supporting another major project, the forthcoming exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s at the Royal Academy of Arts in London (29 June-13 October), which has been co-organised with the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. The show includes 65 works, from oil paintings and sketches to collage and theatre design, many of which are on loan from the National Art Museum of Ukraine and the Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema of Ukraine in Kyiv.

“The Modernist movement in Ukraine unfolded against a backdrop of collapsing empires, the First World War, the fight for independence, and the eventual establishment of Soviet Ukraine," says a Royal Academy statement. “Despite such profound upheaval, this became a period of bold artistic experimentation, and true flourishing of art, literature and theatre in Ukraine.”