In Van Gogh and the End of Nature, New York-based art historian Michael Lobel sets out to demolish the “myth” that the artist was a painter of nature. Instead, he believes that Van Gogh was deeply involved in depicting the industrialised world.

Most of the stream of new books on Van Gogh are glossy picture compilations, but this volume presents a fresh argument. Lobel writes that “given escalating threats climate change poses in our time, the romanticised vision of Van Gogh as the consummate nature painter is, in my view, doing real damage”.

The book’s argument is stark: “His art was deeply engaged with, if not dependent on, modern industry and, more pointedly, industrial pollution, on which he regularly drew for the subjects, concerns, and even the very materials of his work.”

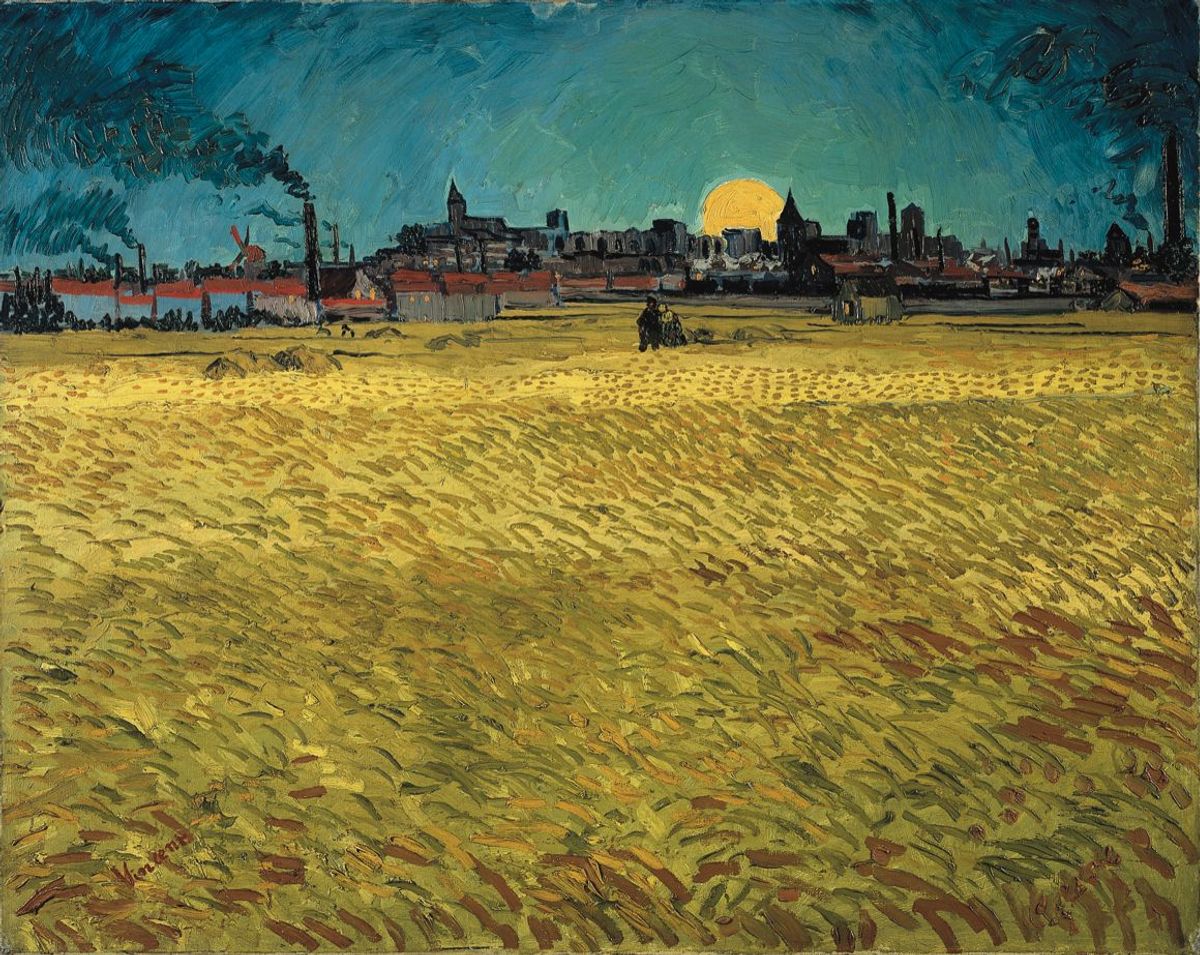

In Van Gogh’s Summer Evening (Soir d’été) (June 1888, displayed at the top of this article), two very distinct worlds are shown, the rural and the urban. As Lobel stresses, Van Gogh could have easily edited out the smoking chimneys, but he made the decision to depict the view, “smokestacks and all”.

Lobel suggests, perhaps tongue-in-cheek, that there should be an exhibition curated around the theme of “Van Gogh: Smokestacks”. As he points out, the artist depicted this industrial structure throughout his career. On his count, there are 30 paintings and drawings which include tall chimneys.

Van Gogh’s Factories at Clichy (May-July 1887)

Saint Louis Art Museum

But isn’t Lobel merely looking back at Van Gogh’s art through 2020s eyes, a period when there is growing concern about climate change and pollution? Although at one point in his book he acknowledges that “we should be wary of projecting our own sensibilities back onto the past”, this often seems to be just what he is doing.

Factory chimneys may occur in 30 works, but trees are probably found in 300. Perhaps Van Gogh included both of these features to add vertical elements to his horizontal landscapes. Smokestacks certainly appear unduly prominent in some of his works, but he also frequently exaggerates the height of his trees. Smoke fanning out in a breeze or belching trains give a sense of motion, enlivening a composition.

Van Gogh’s Bridges across the Seine at Asnières (May-July 1887)

Emil Bührle Collection, long-term loan to Kunsthaus Zurich

I would argue that Van Gogh was not particularly concerned with depicting industry and pollution, and although these motifs appear in his work, this was because they were (and remain) part of modern life. The negative impact of industrialisation does appear in his very early drawings done in the Borinage, the poverty-stricken area of coal mining in Belgium. But he was then primarily concerned with depicting the suffering of the miners, rather than the physical infrastructure of mining.

I am also convinced that Van Gogh truly loved nature, which comes out not only in his art, but also in his eloquent letters. Although Lobel says that we should look for visual evidence in his pictures, the letters are much more explicit when it comes to his thoughts and beliefs.

Van Gogh was born and brought up in farming communities in Brabant, in the south of the Netherlands, and he would never lose his acute awareness of nature and the changing seasons. This contributed to his success as a landscape artist.

Lobel sees things differently, concluding that a decision to regard Van Gogh as a painter of nature is “an idealised, a fantasised, one, because fundamentally it doesn’t jibe with his life experience, the period in which he lived, or the artworks he made”. For Lobel, it is another myth to be exposed. Whatever one’s response to this idea, it is always stimulating to think afresh.

Other Van Gogh news

- The Drents Museum in Assen, in the north of the Netherlands, has successfully acquired a Van Gogh watercolour painted in Drenthe. Landscape with a Farm had been in a private Canadian collection.

Van Gogh’s Landscape with a Farm (September-November 1883)

Drents Museum, Assen

- A Van Gogh drawing titled Two Women strolling, one of them carrying a Kettle (May-July 1882) is to be auctioned by Sotheby’s in London on 25 June. It was last sold by a Cape Town dealer, Joseph Wolpe, in 1980. The estimate is £200,000-£300,000. The woman on the right may represent Sien Hoornik, the former prostitute who Van Gogh lived with in The Hague.

Van Gogh’s Two Women strolling, one of them carrying a Kettle (May-July 1882)

Sotheby’s

- Next year a pair of Amsterdam exhibitions will celebrated the work of the German artist Anselm Kiefer. The Van Gogh Museum is to focus on Kiefer’s admiration for Vincent’s work. The title of the show Where have all the flowers gone refers to the Sunflowers (7 March-9 June 2025). A second exhibition, on Kiefer’s links with the Netherlands, is to take place at the Stedelijk Museum.

Anselm Kiefer, The starry night (2019)

© Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Georges Poncet

- On 20 June a Van Gogh will be removed from the display at the Kunsthaus Zurich because of Nazi-era concerns. The Old Tower (May 1884) was on long-term loan from the Foundation E.G. Bührle Collection, along with other paintings by Claude Monet, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin and Gustave Courbet which are also being taken off show because of Nazi-era concerns. The foundation says that the decision to remove the paintings to storage was taken with the aim of finding “a fair and just solution for these works with the legal heirs of the former owners”. A Kunsthaus spokesperson says that although they “regret” the removal, because of its negative impact on visitors, the foundation had acted “correctly”.

Van Gogh’s The Old Tower (May 1884)

Wikimedia Commons