One of the sculptor Richard Serra’s earliest memories was a moment when, on his fourth birthday, his father took him to the shipyard in San Francisco, close to an undeveloped area that fronted Ocean Beach where they lived, to watch the launching of an enormous tanker. Behind them was an expanse of sand dunes and no blacktop roads; ahead, the sublimity of American industrial might and the distant void of the horizon line. The infant Serra was captivated, feeling at once infinitesimally small yet recognising himself as somehow being in the world, amidst its greatness, and the freedom that comes with that realisation for the first time. Serra never lost that invigorating sense of wonder, and of feeling enveloped in a world far more monumental than himself. These realisations, combined with a brutish love of powerful materials, formed Serra’s subject for more than 60 years.

Serra’s father, Tony Serra, was an emigrant from Majorca and worked as a pipe-fitter during the Second World War, while his mother, Gladys Fineberg, who was Russian Jewish, instilled in him a lifelong love of literature. Serra was the second of their three sons. His early years were spent in his charismatic older brother Tony’s shadow; Tony became a staunch far-left lawyer and activist who defended Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panthers, as well as three members of the revolutionary Symbionese Liberation Army, on murder charges. But the one thing the young Richard Serra had on his older brother was that he could draw, and on rolls of butcher’s paper he scribbled pictures of engine parts to impress his parents. At school, Serra’s muscular, brawny frame led him to become a talented sportsman and he won a football scholarship to Berkeley, but broke his back in his first year: it was “a blessing in disguise”, he later reflected.

What I’m doing in my work ... has nothing to do with the specific intentionsRichard Serra

By the time he transferred to UC Santa Barbara, and majored in English literature, that sleepy coastal town beneath the Santa Ynez Mountains had been transformed into a crucible of intellectual debate, with Reinhold Niebuhr, Aldous Huxley and Christopher Isherwood all writing there. In term time, Serra would write papers on existentialism, including a senior thesis on. Albert Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus, which he described as focusing one’s “relationship to time and its passage, your relationship to your own necessities… and that became a subtext of the way I’ve led my life”. In the summers, he worked at Bethlehem Steel in Alameda, “catching red-hot rivets and sticking them between flanges”. Serra was proud of his working-class roots and found a great deal of satisfaction in labour; he later set up a small removals company in downtown Manhattan called Low Rate Movers, together with his friends the composer Steve Reich, the writer and actor Spalding Gray and the artist Chuck Close.

Serra had met Close as a graduate student at Yale. Like many of Serra’s closest friends, Close had a fractious, competitive relationship with Serra, with Close once saying that “it’s a goddamn good thing he’s a great artist, because a lot of this stuff [his combative, gruff demeanour] wouldn’t be tolerated”. Serra studied under Josef Albers—who entrusted his tutee with proofreading early drafts of his masterpiece The Interaction of Color, the inspiration for a later film work by Serra, Color Aid (1971)—and he might have continued making only what he derided as “knockoff Pollock-de Koonings” were it not for two transformational research trips to Europe. First, in Paris, Serra became obsessed by Constantin Brâncuși’s torqued sculptures, and it was in Paris, in 1964, that he married his Yale classmate Nancy Graves and fell in with Philip Glass’s avant-garde circle of musicians. On a Fulbright grant in Florence in 1966, Serra immersed himself in the city’s Medieval friezes and Fra Angelico’s glistening scenes of beautification, and began working with stuffed and live animals, including chickens, rabbits and pigs, sharing ideas and process with the emergent Arte Povera movement.

Once he moved to TriBeCa in 1967, Serra ran with the Judson Memorial Church scene led by the dancer Yvonne Rainer, got divorced from Graves, and fell in love with the artist Joan Jonas. Making work at a time that might be historicised as the cusp between Minimalism and Post-Minimalism, Serra and his downtown compatriots, who included Robert Smithson and Donald Judd, turned to unconventional, industrial materials and emphasised the relationship between the work and its (often urban, public and context-dependent) environment.

Sculpture was no longer something human-sized to be put on a plinth, but an immersive arena in which the spectator’s phenomenological experience took on a new importance. The artist’s creative intentions gave way to everyone else’s subjectivities. “What I’m doing in my work… has nothing to do with the specific intentions,” Serra said in a 1973 interview with Liza Bear: “If I define a work and sum it up within the boundary of a definition, given my intentions, that seems to be a limitation on me and an imposition on other people of how to think about the work.”

Criticism and controversy

What followed was two decades of restless invention, scattered success and bitter disappointment, as well as much controversy. In 1971, a rigger was crushed to death during the installation of one of Serra’s sculptures outside the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. While he was cleared of any malpractice, waves of criticism followed wherever he went. Simmering malcontent came to a boil a decade later when a public furore attended Tilted Arc (1981), commissioned by the General Services Administration in Foley Federal Plaza, Manhatttan, and consisting of a slightly leaning wall of rusting steel 12ft high and 120ft long. Criticism ranged from the work causing a rat problem to the speculative possibility of it being handy for a terrorist to use as a kind of springboard to blow up an adjacent building. A television feature depicted a pile of burning rubbish under an underpass, followed by the words “New Yorkers have had enough of this” before panning to Tilted Arc. Serra received, he said, “a lot of criticism not only of my sculpture but of my personality”. Supported by his second wife, the German art historian Clara Weyergraf, who encouraged him to fight the case in the courts, Serra lost a lengthy public lawsuit and the sculpture was removed under heavy police supervision. Arguing for its importance as a site-specific work, Serra refused to display it again. But, “If any artist disproves the old F. Scott Fitzgerald line that there are no second acts in American lives,” mused Hal Foster, whom Serra took under his wing as a twenty-something critic, “that artist is Serra.”

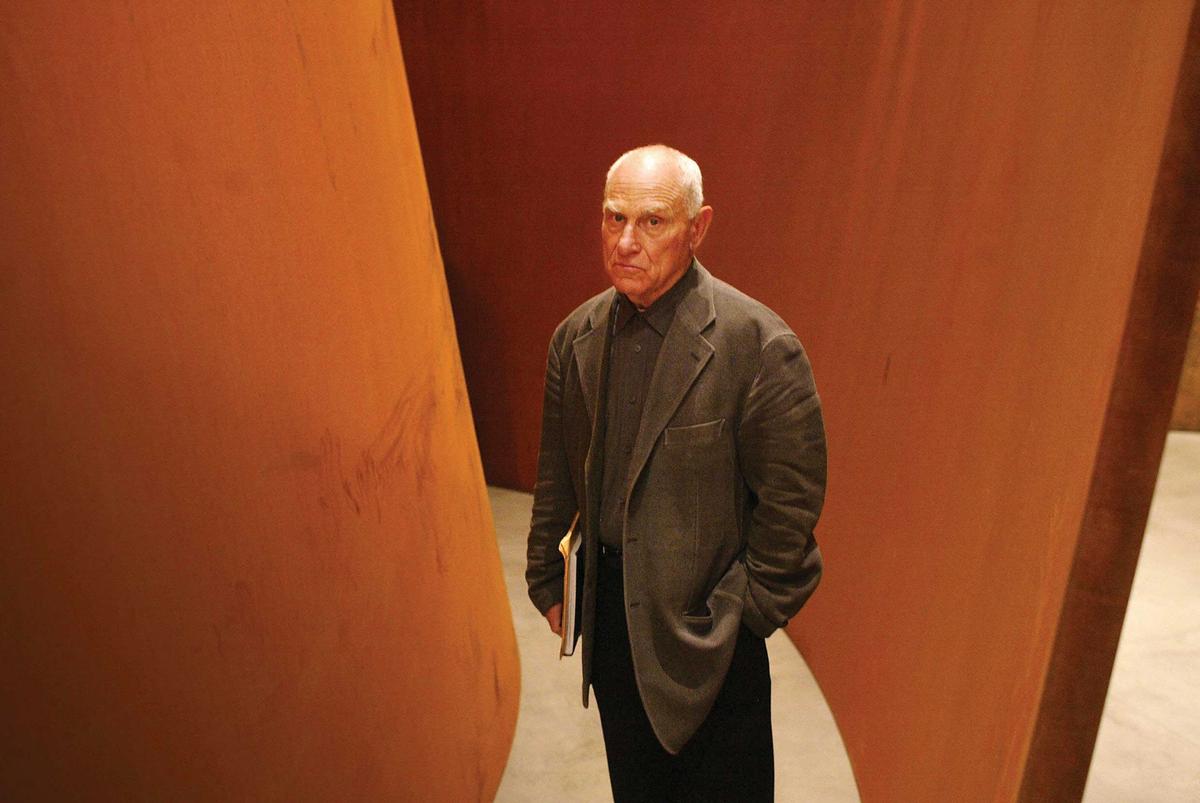

Inspired by the curved shapes of the Italian architect Francesco Borromini’s church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (1646), in Rome, which beguiled Serra on a visit in the 1990s, Serra’s revelatory Torqued Ellipses series destabilise our experience of space. We enter a twisted torque, made using a rare steel-blending machine and computer technology to produce raw steel less than six inches thick. These flat, upright structures seem to defy the laws of gravity by standing autonomously without any proof of affixed screws or internal structure to hold them in place. “The medium of form,” Serra later said, “is above all the rhythm of the body.” Stepping into his own works, Serra must have been returned to his experiences watching the shipyards as a child.

Over the next three decades, Serra made several commercially successful sculptures, often wincingly heavy, monumental and site-specific: Inside Out (2013) is an oxidised labyrinth in which the viewer has a choice, facing four entrances that are also exits, over how they negotiate their journey; East-West/West-East (2014) consists of four steel monoliths in the Qatari desert; Four Rounds: Equal Weight, Unequal Measure (2017), is made from four 82-ton forged cylinders of varying dimensions, and is on permanent display at Glenstone museum in Potomac, Maryland. At the time of his death, Serra was both the most revered and the most sought-after sculptor in the United States.

On the occasion of a major three-part exhibition in 2016, which saw a new generation of artists queuing around the block to get into Gagosian’s gargantuan West 24th Street gallery, Briony Fer wrote on what she called “Serra’s paradox”: “Richard Serra’s work over the past 50 years has come to define sculpture, not because it is typical of what sculpture became in the aftermath of Minimalism but precisely because it isn’t. His work has turned out to be both so singular as to be unrepresentative of an agreed canon and to have offered the most persuasive case for sculpture in its own distinctive terms.”

As a man and as an artist, Serra will be defined by his paradoxes: the red-blooded machine-maker who tenderly loved Emerson’s poetry, the acerbic and sometimes misanthropic troublemaker who was such a generous champion of younger artists and critics. But, above all, Serra reminds us that containing multitudes is not the same as lacking conviction or failing to stick to one’s guns. Whatever his legacy, no one could accuse him of that.

Richard Serra, born San Francisco 2 November 1938; married 1964 Nancy Graves (died 1995; marriage dissolved 1970), 1981 Clara Weyergraf; died Orient, New York, 26 March 2024.