Some people are so fed up with the present UK government that they cannot wait to see someone else—anyone else—in power. But how would they feel if they woke up one morning to find a bunch of artists in charge instead? Let us say that the shark-pickler Damien Hirst was handed the environment brief, while serial-shredder Michael Landy was left alone with sensitive documents of state. That was the kind of dizzying prospect facing the Russian people in the tumultuous years of 1917 and 1918, when the radical artists Kazimir Malevich and Marc Chagall joined the government payroll, though admittedly the Russians had even more pressing matters before them at the time. In the space of 18 months, the last tsar (Nicholas II) was deposed and murdered with his family, and the Bolsheviks were on their way to establishing communism in Moscow. But in artistic and bohemian circles, there was a brief, shining moment when it seemed as though Russia would make good on Percy Bysshe Shelley’s claim that poets (and artists) are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

A futurist blasts the past

On 15 November 1917, readers of the Moscow newspaper Izvestia learnt that Malevich, then still in his 30s, was their new “Interim Commissar for the Preservation of Valuables in the Kremlin”. Russia was entrusting its most sacred patrimony—such as centuries-old cathedrals and the Romanovs’ Fabergé eggs—to a man who called himself a “futurist” and urged his countrymen to forget their past. “All that has been made, was made for the crematorium,” he sneered. This was not putting a lunatic in charge of the asylum; it was more like releasing a pyromaniac into the treasure chamber with a jerrycan of petrol. Sure enough, the Kremlin was soon at the centre of a fierce conflagration, although Malevich, the unlikely janitor, was not to blame: the national citadel was changing hands between conflicting factions as Russia’s political destiny was thrashed out.

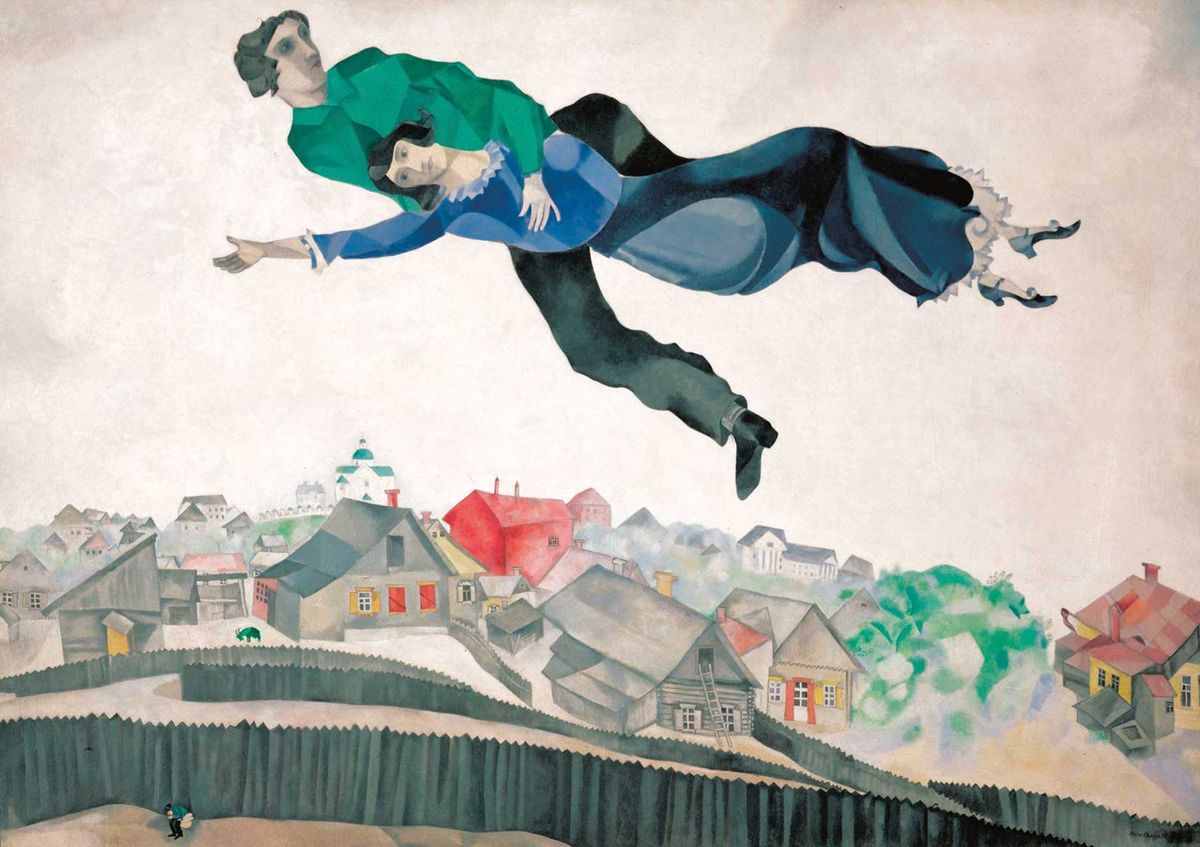

In early 1918, Chagall was asked to become commissar for the arts in the city of Vitebsk, now part of Belarus, where he had grown up. One of his tasks was to organise a festival marking the first anniversary of the revolution. The workers liked the motifs of outsize beasts he designed, but he imagined his fellow apparatchiks muttering to each other: “Why was that cow green and why was that horse flying through the air? What have they got to do with Marx and Lenin?” Chagall was a fish out of water: his magical paintings of flying fish soaring over rooftops could almost be self-portraits.

Malevich had produced Black Square (1915), one of the first works of modern art to outrage its bewildered audience. He ordered that it should be displayed high up on a wall, in the place Orthodox Russians reserved for icons. Born into a Polish family, the supremely self-assured artist vied for influence with the more stolid Russian Vladimir Tatlin, who constructed a great monument to the revolution, “Tatlin’s Tower”. Perhaps unfortunately, it resembled Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Tower of Babel (around 1563). Geometric glass forms could be seen rotating inside the structure, or at least that was the idea. On the day Lenin came to see the tower in action, Tatlin’s assistant was concealed inside it to crank the machinery. But not even this could bring it to life. “Lenin watched, said nothing, and walked away,” is the ominous coda to the story in Sjeng Scheijen’s new book The Avant-Gardists.

Shattered dreams

Readers of Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago (1957) will be familiar with the chaos and upheaval of these times, but Scheijen, an acclaimed biographer of the Ballets Russes impresario Sergei Diaghilev, has recovered its

remarkable and little-known art history. In his exemplary account, it was a moment of fierce optimism followed by shattered dreams, of hysterical highs and crushing lows. I kept thinking of the famous image from the Soviet propaganda film Battleship Potemkin (1925) of the woman shot through the eye, her face frozen in a wide-mouthed expression of shock.

Malevich and his acolytes may have imagined themselves as men and women of the future, but the reader has the advantage on them of knowing what will happen after Stalin takes control and unleashes his “terror”. Art must be purged of decadent and bourgeois tendencies. One by one, the avant-gardists are “disappeared”, either by their own hand or the dictator’s whim. Malevich was imprisoned and fell ill with the prostate cancer that eventually killed him. His old rival Tatlin was publicly denounced and removed from office. Only Chagall lived into old age, dying in Paris aged 97.

Malevich’s Black Square turned out to be a looking glass, reflecting the dark-as-pitch reality of the revolution. It put me in mind of Saul Bellow’s observation: “Death is the dark backing that a mirror needs if we are to see anything.” Like one of those Fabergé eggs that Malevich looked after, Scheijen’s book is multi-faceted, handsome on the mantelpiece—and blood soaked.

• Sjeng Scheijen, The Avant-Gardists: Artists in Revolt in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union 1917-1935, Thames & Hudson, 504pp, 128 colour and b/w illustrations, £35 (hb)

• Stephen Smith is a journalist and broadcaster