Researchers studying a 4,500-year-old ancient Egyptian skull have identified what might be an early case of cancer surgery. Held in the University of Cambridge’s Duckworth Collection, the skull bears tiny cut marks, visible under microscope, which indicate that the Egyptians operated on tumours or examined them after the person’s death.

“This was very unexpected,” says paleopathologist Edgard Camarós of the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, and co-author of the research paper published in the journal Frontiers. “We were very sceptical at the beginning when we saw the cut marks in the microscope, although they were very clear. It took a bit to realise we were visualising the evidence of a milestone in the history of medicine.”

Cancer was not understood in antiquity—it was “a medical mystery,” Camarós says—but the ancient Egyptians did recognise tumours and swellings. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, a medical text dated to around 1600 BC, may even describe a case of breast cancer. Now, the team’s investigation reveals that although the Egyptians had no treatment for cancer, they may have tried to operate on the disease.

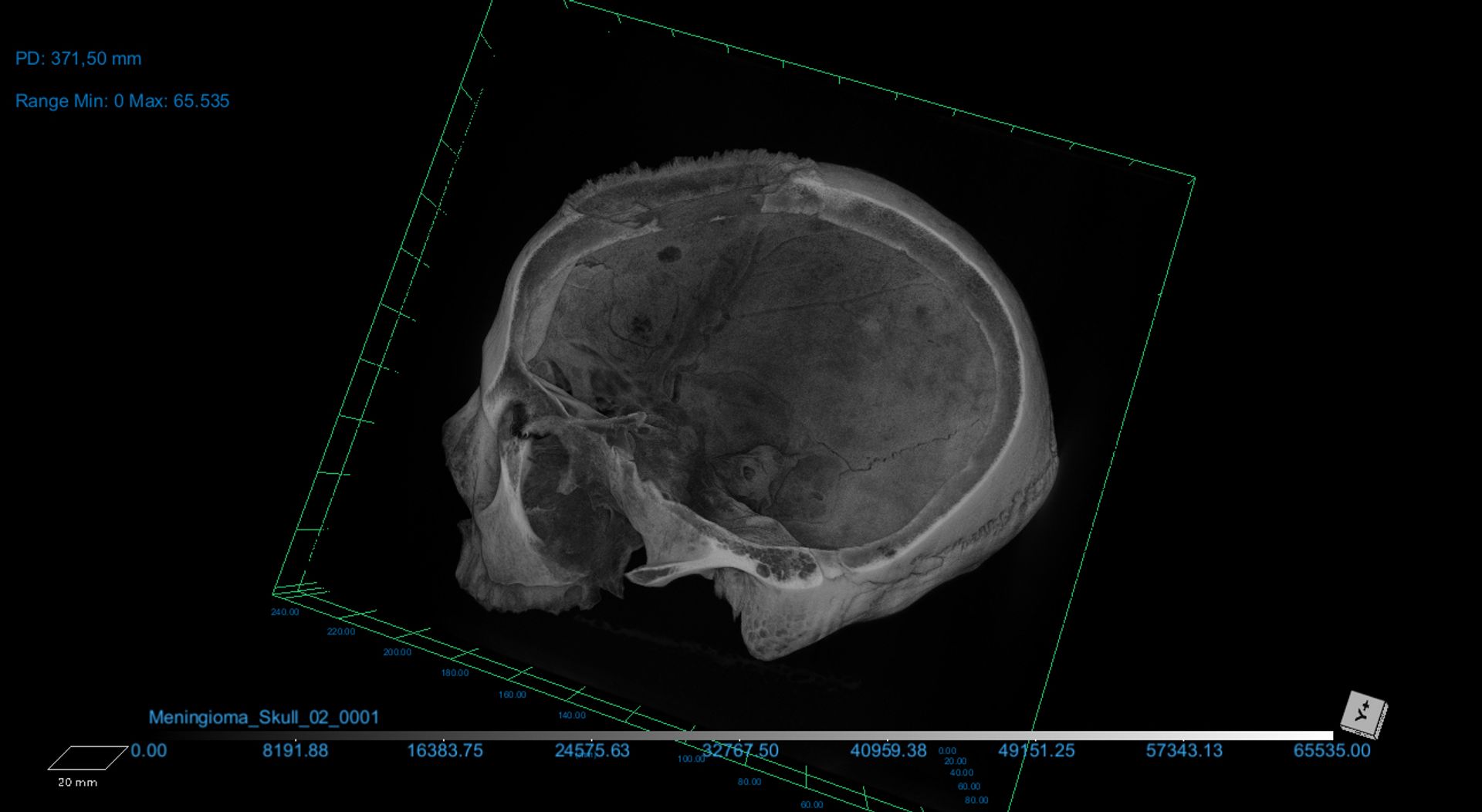

Camarós and his colleagues made the discovery while examining a skull that belonged to a man who died at around age 30 to 35, and lived sometime between 2687 and 2345 BC—ancient Egypt’s pyramid age. Using micro-CT scanning and microscopic bone surface analysis, they investigated a large lesion (an area of damaged tissue) and around 30 small and round metastasised lesions spread across the skull. It was around two of these small lesions that they spotted the tiny cut marks.

Cutmarks found on the skull, probably made with a sharp object

Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024

An ancient physician appears to have made these incisions either shortly before the patient died, perhaps to remove the cancerous tumours, or after death to examine and better understand them. The cut marks were not made during mummification, the team write in the research paper.

The team also investigated a skull that belonged to a woman who was more than 50 years old, lived roughly between 663 and 343 BC, and was buried at Giza. Her skull bears a large lesion created by a cancerous tumour and two healed lesions. One of these latter wounds appears to have been inflicted by a right-handed individual with a sharp weapon, who attacked her from the front. It’s possible that she was involved in warfare, the team suggest, and only survived the attack because of medical treatment.

The team also examined the skull of a woman who lived between 663 and 343 BC, and they say she may also have received medical treatment. Both skulls were examined using microscopic analysis and CT scanning

Tondini, Isidro, Camarós, 2024

“It’s exciting thinking that we have discovered the first steps in our understanding and exploration of what we nowadays call cancer,” Camarós says. “Successful modern medicine treating cancer had a beginning, and that surgical intervention is the origin of that history.”