It was one of the biggest art scandals of the Weimar Republic. George Grosz, whose caricature-like figuration criticised the social and political realities of Berlin in the early 20th century, stood trial for a drawing that showed Jesus on a cross with a gas mask, titled Maul halten und weiter dienen (Shut up and do your duty).

The work was created, along with some 300 others, for Erwin Piscator’s staging of The Good Soldier Švejk, in 1928. Piscator’s adaptation of the dark satirical novel by the Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek was considered a milestone in theatre history, not least because of Grosz’s set design and the use of film projections on stage, which included animated sequences with several soon-to-be-banned drawings.

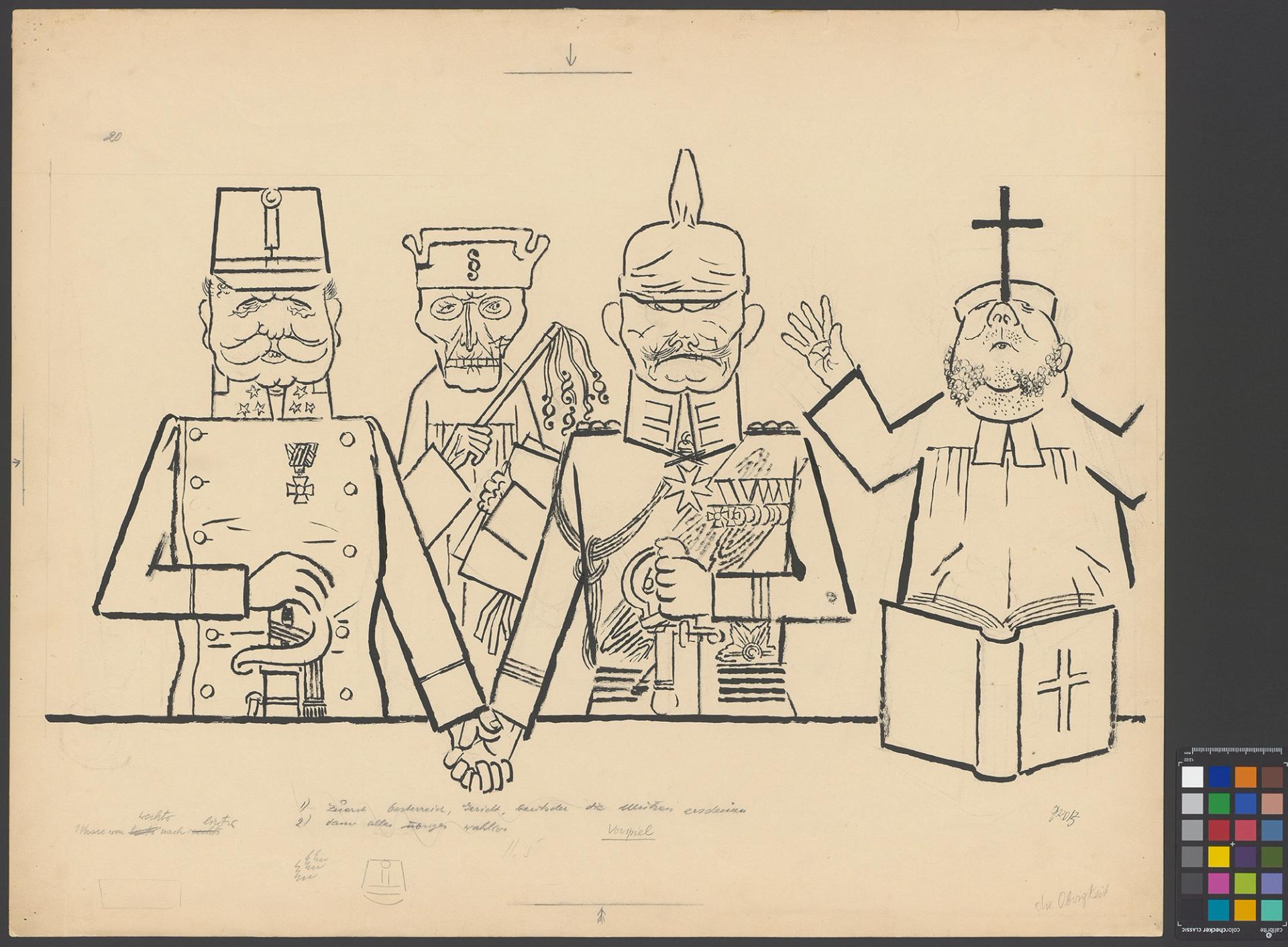

One of George Grosz's drawings for Erwin Piscator’s staging of The Good Soldier Švejk © Estate of George Grosz, Princeton, N.J. / DACS - DESIGN AND ARTISTS COPYRIGHT SOCIETY LIMITED

Grosz and the publisher of Malik Verlag, Wieland Herzfelde, printed a graphic portfolio with a selection of drawings that were created for the animated sequence. The portfolio landed them in court, as three sheets, the image of Christ wearing a gas mask, Seid untertan der Obrigkeit (Be subjects of the authorities) and Ausschüttung des Heiligen Geistes (The Pouring Out of the Holy Spirit) were confiscated for “publicly insulting the institutions of the Christian churches”. At the end of a protracted three-year trial both defendants were acquitted, but were ordered to render the graphics and printing blocks unusable.

However, Herzfelde hid the Christ drawing for years, and in the 1980s bequeathed it to Berlin’s Akademie der Künste (Academy of Arts), one of Europe’s oldest cultural institutions, founded in 1696. This week, on 22 May, the academy launched an exhibition of an additional 13 sheets from the Soldier Švejk series, which were recently acquired for around €300,000. Twelve sheets came from the estate of George Grosz including the previously banned work Seid untertan. Another, a study for the lost drawing Ausschüttung des Heiligen Geistes, was acquired from a private collection in Italy.

The little-known works, which are so central to Grosz’s legacy and political commitment, will go on public view in July at Berlin’s Kleine Grosz Museum, the first institution dedicated to Grosz’s oeuvre. The original set design for Soldier Švejk included life-size figures, rendered from the drawings in papier-mâché, which moved about the stage on a conveyer belt. For the exhibition, the museum will reproduce some of those figures, based on the few remaining photographs of the original stage. Ralf Kemper, a co-curator of the upcoming exhibition, tells The Art Newspaper that the show, which will loan additional works-on-paper from other private collections and museums, presents a rare opportunity “to see them all together in one room”.

“They are in good condition generally, but works on paper can only be shown for three or four months a year. They might not be shown again for a long time,” Kemper says.

• Was sind das für Zeiten? – Brecht, Grosz und Piscator, the Kleine Grosz Museum in Berlin, 4 July-25 November