The British artist and director Steve McQueen has achieved a formidable reputation in the worlds of both art and film over the past two decades. McQueen went from winning the Turner Prize in 1999 to representing Great Britain at the Venice Biennale in 2009 before winning an Oscar in 2014 for his feature film 12 Years a Slave (2013), becoming the first Black director to win a Best Picture award. He has been knighted for his services to art and film and has been given major exhibitions in museums worldwide. No other figure currently commands such high esteem across both sectors.

Whether he is making work for the cinema, the television screen or for the spaces of an art gallery, McQueen’s hallmarks continue to be a formal rigour wedded to tender and sometimes excruciatingly unflinching depictions of human endurance. The physical intimacy as well as the objectivity of the camera lies at the core of his work. This can be seen in Grenfell (2019), McQueen’s 24-minute film dedicated to the 72 people who died in the Grenfell Tower fire tragedy in London, as well as in his latest four-and-a-half-hour experimental documentary Occupied City (2023)—made with his partner Bianca Stigter—which chronicles the five-year Nazi occupation of Amsterdam.

The bass sound does something to your psyche, your body, it rattles your ribcage

Yet, despite his successes as a film-maker, McQueen considers himself to be primarily an artist. This month he returns to the gallery with Bass, a new commission for the ground-floor gallery at Dia Beacon in New York state, composed solely of light, colour and sound. The show has been curated by Donna De Salvo and the work co-commissioned with the Schaulager in Basel, where it will travel to in 2025. Later this year, McQueen’s video installation Sunshine State (2022) will go on show at Dia Chelsea in New York.

The Art Newspaper: Bass is your most abstract work yet with no screens, no projections, just 30,000 sq. ft filled with coloured light and sound. What’s the thinking behind it?

Steve McQueen: It started off about 20-odd years ago when I was thinking about light and I was thinking about colour and mass and visibility. I was talking to this physicist about the density of light and how light travels and how we see and how we look. Then with the audio aspect of it, I was thinking of the Middle Passage [the slave ship voyage across the Atlantic Ocean], the Atlantic crossing and the whole idea of limbo and not being here or there. Also, one of the last conversations I had with Okwui [Enwezor, the Nigerian curator] when he was in hospital was about the abstraction in my work.

Your feature film 12 Years a Slave confronted us with a very specific account of the horror of enslavement, and now in Bass the trauma and violence of displacement is evoked using light and sound.

It’s about presence, your own state of mind and being sensitive to oneself in the place that you’re at. And that provokes other things to come into play, other narratives and other experiences. That’s what light and sound does. What I love about light and sound is there’s a fluidity to them, they can be moulded into any shape. Like a vapour or a perfume, they can sneak into any nook and cranny. And I love that beginning point where something isn’t a form as such, but it is all-encompassing.

Light boxes mounted into the ceiling bathe the space in pure saturated colour that changes almost imperceptibly through the entire chromatic spectrum over nearly half an hour. Why all these colours?

The colour aspect was to embrace, to engulf, to encapsulate everything in that environment. But also to provoke thought within that context for individuals, whoever they might be. I just wanted to see that cycle, but it’s almost like things occur without you knowing it has happened. All of a sudden you’re in red, and all of a sudden you’re in yellow: the light moves so slowly that you can’t really see it happening.

Steve McQueen’s Sunshine State (2022) uses imagery from the 1927 film The Jazz Singer and will go on show at Dia Chelsea in New York later this year Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Studio Hans Wilschut/IFFR; © Steve McQueen and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan

The other component of Bass is a specially commissioned soundscape made on site by a multigenerational group of musicians all playing bass. They are led by Marcus Miller, who was a bassist for Miles Davis, as well as Aston Barrett Jr of The Wailers band, Mamadou Kouyaté from Mali playing bass ngoni, Meshell Ndegeocello on electric bass, and the young musician Laura-Simone Martin on upright bass. How did this work? Were they all playing in the space at the same time? Was the piece rehearsed or improvised?

It was totally improvised. Marcus and I had talked beforehand about the music and how I wanted it to be. But these musicians had never worked together before. On the day we started recording in the basement of Dia Beacon I had a conversation with them, then they started to play, and that was it. It just happened in those two days. We were thinking of going afterwards to a recording studio and continuing, but what was happening in that environment could never be recreated in a studio. It was extraordinary. You would think it was written, but it’s all improvised.

And why did you exclusively use different forms of bass?

Usually, the bass is in the background holding things together, but I wanted to put it in the foreground. I remember having this conversation with Quincy Jones when I did [the five-night concert series] Soundtrack of America with him at The Shed in New York. He said that the electric bass changed music, and I just love that idea. The bass sound does something to your psyche, your body, it rattles your ribcage. It’s the basis of Black music. So it fed into this visceral want. It’s transformative, transcending.

You’ve talked about this work in the context of the historian and social theorist Paul Gilroy’s call for the creation of “new chronotopes”, new configurations of time and space, and the part that they play in forming the Black Atlantic. There’s a lot to unpack here.

For me it was about being in this state of limbo. The space between the crossing: that particular state of not arriving, and leaving, and what that is. The bassists are all from different aspects or places of the diaspora—from Africa, from America, from the Caribbean—and here they all come together to investigate, to interpret or just feel that idea of being in this place or non-place, whatever you want to call it.

In a way, the players themselves embody the Black Atlantic, this transnational culture that both transcends and fuses specific nationalities and ethnicities to make something new.

Absolutely. There’s a fluidity. It’s about the past, it’s about the present and it’s about the future. In our lives at this time there is a certain kind of flux and of destabilisation, and with this work, through going back to certain points, I was wanting to find out where we are and how far we’ve come.

Yet the physical violence of being abducted by force from your home and put in the belly of a ship still seems to be the starting point for this piece.

Yes, but it’s always about the mind. I am a survivor; I am the evidence of that. Black people are post-apocalyptic people. And because we’re totally devastated, totally displaced, in a way this means we’re brand new. We’ve had to invent—literally to make our own language through the immediacy of sound and music. We took things that were discarded and thrown away and made a language out of it, which was music. In Trinidad, it’s oil drums and steel pans, in the South Bronx it’s hip-hop—which had its roots in Jamaica—and so on. Through sound we’ve invented our own language, we laid the foundations of popular music. We are a post-apocalyptic people, and that’s the starting point—this limbo, and then the need to invent, to reinvent.

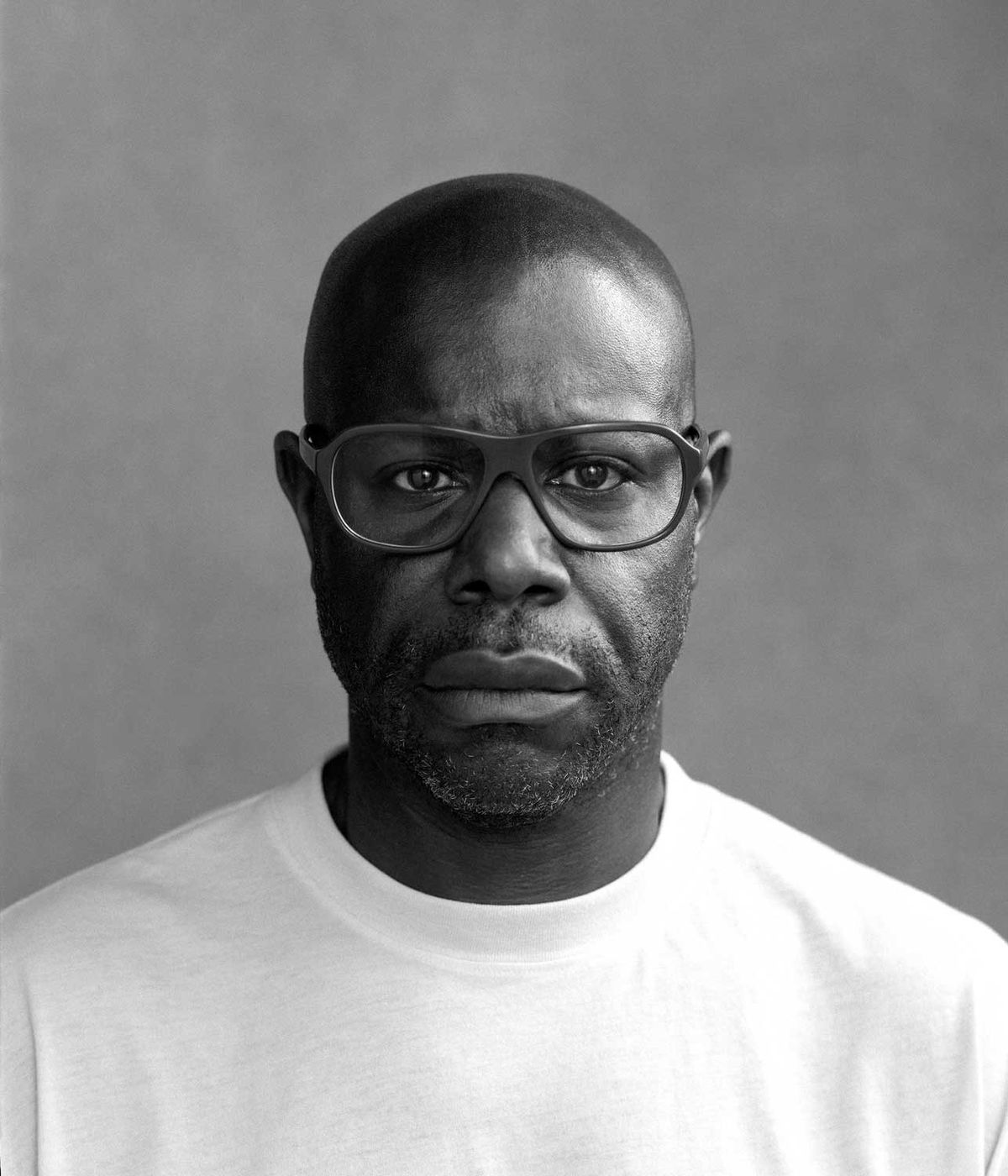

McQueen’s Bass at Dia Beacon in New York State will explore light and sound, which “like a vapour or perfume... can sneak into any nook and cranny”

Photo: Randy Gibson. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation

Biography

Born: 1969 London

Education: 1990 Chelsea School of Art, London; 1990-93 Goldsmiths, University of London; 1993-94 New York University Tisch School of the Arts

Lives and works: London and Amsterdam

Key shows: 1997 Museum of Modern Art, New York; 1999 Institute of Contemporary Arts, London; 2007 Imperial War Museum, London; 2009 British Pavilion, Venice Biennale; 2013 Schaulager, Basel; 2016 Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; 2019 Tate Britain, London; 2020 Tate Modern, London; 2022 Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan; 2023 Serpentine Galleries, London

Represented by: Thomas Dane Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, Paris and Los Angeles

• Steve McQueen: Bass, Dia Beacon, Beacon, 12 May-April 2025

• Steve McQueen, Dia Chelsea, New York, 20 September-January 2025