How safe are the performers in Marina Abramović’s performances? As a high-profile lawsuit makes its way through the courts, questions are being raised over museums’ duty of care towards the people working in the artist’s boundary-pushing exhibitions.

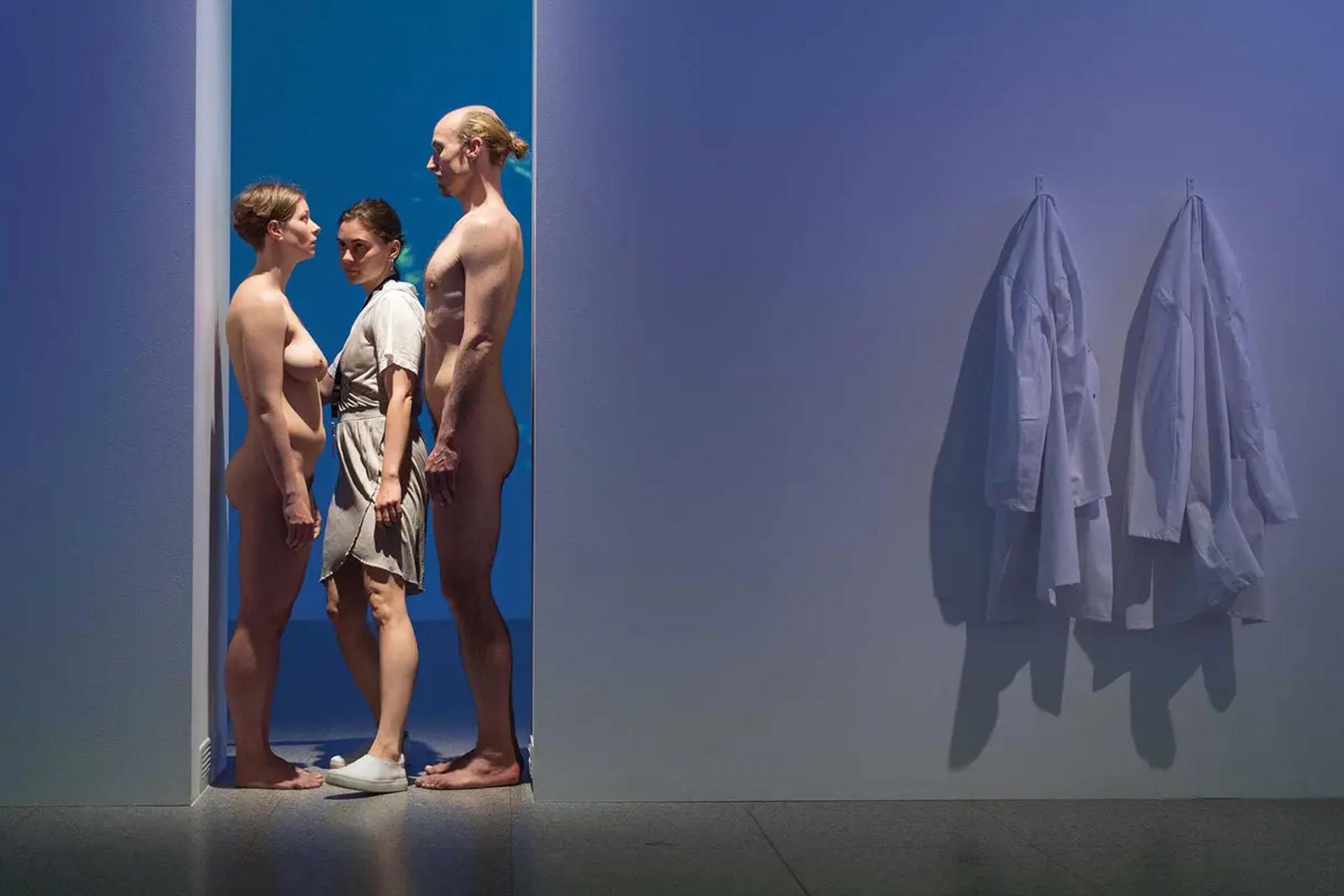

Recent museum shows, including those at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) in London, have seen performers recreating physically challenging works such as Imponderabilia (1977), which involves members of the public walking between two naked performers stood facing one another in a narrow doorway.

In January, news emerged that an artist who had performed in Abramović’s retrospective at MoMA in 2010 was suing the institution, alleging he was sexually assaulted while taking part—and that the museum was liable.

The incident at MoMA may not have been a one-off occurrence. In the run-up to the RA’s blockbuster show on the artist in 2023, staff were allegedly told that issues around visitor behaviour have taken place at “almost every major show” of Abramović’s work, according to a museum employee. The RA faced its own challenges during the show, such as allegedly having to escort out a visitor found with a camera pen.

“The museum bears responsibility as the institution charged with translating an artist’s vision while ensuring visitors’ and performers’ safety. However, a restaging also presents an opportunity to perhaps reconsider past performances in light of evolving societal values,” says Elizabeth Webster, a lawyer and writer.

When you agree to do that piece, you need to accept the consequencesOlivier Varenne, Mona

In a statement to The Art Newspaper, the RA says: “The welfare of all the performance artists who participated in the Royal Academy’s Marina Abramović exhibition was our top priority and we had plans in place, with a particular focus on safety and wellbeing, to ensure they were fully supported. It is the Royal Academy’s policy not to disclose information regarding security within the galleries.” The Marina Abramović Institute, which collaborated on the exhibition, did not respond to a comment request.

John Bonafede, the “re-performer” who is suing MoMA, says he was assaulted seven times by five different visitors during the run of the show. He said every perpetrator was “an older male”, and that each would “drop his hand, covertly reach between [Bonafede’s] legs, and fondle and/or grope [his] genitals, lingering for a moment before moving through into the next gallery room”. The lawsuit also alleges that Bonafede witnessed a female performer being sexually assaulted while taking part in Imponderabilia; additionally, he “discussed incidents of sexual assault on other [Imponderabilia] performers with other re-performers”.

Bonafede alleges that he reported four of the five alleged assailants to MoMA staff. He also says that following the alleged assaults, he went on to “suffer years of emotional distress, and [the events] substantially harmed [his] mental health, body image and career”. MoMA moved to dismiss the lawsuit in February, arguing that Bonafede “elected to perform” in the work “with the expectation and understanding that MoMA patrons would have inadvertent contact with his naked body”. The museum also stated it had provided support. “MoMA hired a stage manager to serve as a liaison between the performers and MoMA curators,” the memorandum said. “Performers and MoMA staff created a signal system to alert security in the event performers were inappropriately touched, the protocols for which were included in the performers’ handbook.” (The handbook was brought in around a month into the run of the show—a time when reports of assault were surfacing in publications such as The New York Times.) That visitors “inappropriately touched” Bonafede was “unfortunate”, MoMA lawyers said, but added that his arguments “do not give rise to any legal cause of action”.

Risky business

Physical risk has always been at the heart of Abramović’s practice, says Sophie O’Brien, the head of curatorial and learning at the Bundanon Art Museum in New South Wales, Australia. For example, in the piece Rhythm 0, performed in 1974, members of the public were invited to pick up tools—including a saw, an axe and a gun—and use them on the artist in whatever way they saw fit, with participants growing increasingly violent in their actions as time wore on. Abramović has “always been on the edge of asking questions about agency and free will and our relationship to one another”, O’Brien says. But in no way, she continues, does this “condone assaulting or groping or anything else. There are always boundaries for safety for performers and for the public”.

O’Brien has been involved in two Abramović projects, including Marina Abramović: 512 Hours, which she curated at London’s Serpentine Galleries in 2014. She only experienced one notable incident of a man “smashing up a bed” and being asked to leave. She acknowledges, however, that the participants—most of whom were members of the public—were fully dressed and in a public space, so “it would be quite hard to undertake some sort of surreptitious behaviour”.

Echoing MoMA’s argument, Olivier Varenne, the artistic director of the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona) in Hobart, Tasmania, who co-curated the museum’s Marina Abramović: Private Archaeology exhibition in 2015, says: “Marina is pushing the boundaries of what’s possible or not, and what’s acceptable or not, and when you agree to do that piece as a performer, you need to accept the consequences.

Mind the gap: Imponderabilia was restaged at the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn in 2018, as part of the retrospective The Cleaner; the museum says that one performer was “approached” on their way home and via social media Photo: Marius Becker/dpa/Alamy Stock Photo

“If someone grabs your balls while you’re passing, that’s not part of the piece. It’s not acceptable.” Yet, he adds, “When you sign up to be rubbed all day long by visitors, if there’s a little hand coming by, I don’t find it personally such a big deal. I find it a big deal if it’s a proper aggressive gesture, but it’s part of the work to be rubbed against.”

He compares the act of groping a performer to vandalising a work of art. “People should not grab a painting or a sculpture, or throw tomato soup on the Mona Lisa. The person who grabs the balls of a performer should be punished, [much like] someone touching a painting should be.” It is not, he says, the fault of the museum or the nature of Abramović’s work. “It has to do with the person who did it. They’re an idiot.”

Webster, however, believes museums should take more responsibility. “Nude performance artists should feel as safe at work as anyone else. Their decision to expose themselves to the public doesn’t diminish their autonomy over their own bodies. While museums always balance the competing interests of an artist’s intention with the need to protect performers, I think that the pendulum must swing toward shielding the most vulnerable in the room,” she says.

Webster adds that Abramović has a role to play. “Her performances [from the 1970s] blurred the line between performers and audience members—and also at times showed the darker urges some individuals have to dominate others. Yet now, Abramović herself is the powerful one. While she perhaps hasn’t always prioritised her own safety, she could nonetheless adjust modern performances to support artists’ needs.”

Museums have been working hard to adapt Abramović performances, applying a range of regulations and guidelines—at times to Abramović’s consternation. Last year, The New York Times reported that lawyers at MoMA had, before the 2010 retrospective, insisted that performers of Luminosity (1997)—which involves sitting naked on a bicycle seat, limbs outstretched—needed to wear a helmet and safety belt. “I said, ‘This is ridiculous!’” Abramović remarked, adding that she agreed to take on $1m in personal liability to prevent the changes.

A spokesperson for the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, Germany, which hosted a wide-reaching retrospective of the artist’s work in 2018, says a performer was “approached” on their way home and via social media during the show. The spokesperson says staff regularly checked on the employee’s wellbeing and suggested a signal that they could use should the person return. Stage managers, they add, were hired to take care of performers, and there were regular briefings in which adjustments were made to the show based on their feedback.

Indeed, putting on an Abramović exhibition has the air of a military operation. Codes and codewords are abundant. According to The Art Newspaper’s source at the RA, a codeword was used for Abramović when she was on site three or four times a week. Additionally, there were up to three people—including gallery staff and a representative from the Marina Abramović Institute—watching a performance at any one time. RA staff were reportedly warned about the potential of triggering subject matter in the exhibition, including violence and nudity, and asked to let supervisors know if they had any concerns working in the galleries.

At the Serpentine, O’Brien notes, there were specific guidelines for dealing with the public. Gallery staff, she says, had several months of training in Abramović’s methods, as well as in working with the public to ensure that they were comfortable in the unusual circumstances. There was a “huge schedule”, she says, with people swapping out regularly over the course of the 512-hour performance, and twice-daily meetings where staff checked in with one another. There was also a security team—disguised as performers in the room—watching Abramović.

Looking ahead

The verdict in the MoMA lawsuit is likely to have an impact on the way performance art is staged in the future. “Based on Abramović’s previous work, museums and performers alike are on notice now that visitors can behave predatorially,” Webster says. “While it’s reasonable for institutions to evaluate prospective performance art on a case-by-case basis, some of Abramović’s work is undeniably high risk to performers. They’re high risk for museums, too. Bonafede’s lawsuit demonstrates that nude performance art—even with well-intentioned safeguards such as security and a signal system in place—can open museums to liability.”

Eugenio Viola, a critic and curator who co-organised The Abramović Method at PAC—Contemporary Art Pavilion, Milan, in 2012, says the onus should be on museums to adapt: “The challenge, from an institutional perspective, is to [perform] them in absolute safety, both for the public and for the re-performers.”

If they fail in that task, Webster argues, performers should have the ultimate say. “Nude performance artists should always feel empowered to walk, rather than enduring assault—even if their exit results in indelibly disrupting a performance. A person isn’t a prop.”