Dutch traders had visited the area of North America that is now New York in the early 17th century, but it was not until 1624 that colonists arrived for permanent settlement. By 1660, the colony of New Amsterdam had reached what would be its peak before the 1664 English takeover. A detailed map known as the Castello Plan—on view until 14 July at the New York-Historical Society—shows the wall at the edge of the clusters of homes that would later give Manhattan’s Wall Street its name, as well as the path of today’s Broadway curving up from the imposing Fort Amsterdam. However, 400 years later, beyond these traces in the streets there is rare physical evidence of the Dutch colonial era.

What remains is easy to overlook, surrounded by the centuries of development that followed, but frequently speaks to the foundational divisions within the future New York City. Enslaved people were brought to the colony as early as 1626 by the Dutch West India Company, while violent attacks by Dutch colonists on the Indigenous population forcibly removed them from their land.

“In preserving Dutch historic sites, I think it’s important that we’re not just telling the story of the Dutch who came here and built these houses,” says Meredith Sorin Horsford, the executive director of the Historic House Trust of New York City (HHT). “It’s really important for us to tell a more complete and robust story of history and think about other groups who were a part of that period of time.”

HHT has a partnership with the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation to advocate for and support the preservation of member sites that are publicly owned and located on park land. HHT’s online Dutch Heritage Trail, launched in 2021, includes 11 locations that range from the Alice Austen House on Staten Island—expanded from a 1690 one-room Dutch farmhouse—to later structures like the Dutch colonial-style Dyckman Farmhouse in Manhattan, which was built in 1784. Although they can stand out as curious relics (the white-clapboard Dyckman Farmhouse looms over Broadway from its elevated perch nestled between apartment buildings), Horsford emphasises that they are not like objects behind glass.

“These places don’t exist as static historic structures that just sit there and continue to grow older,” she says. “They are dynamic, integrated pieces of their community.”

Horsford was previously the executive director of the Dyckman Farmhouse, where she launched an initiative to research free and enslaved Black people who lived and worked at the site, with artists humanising their stories—such as Reggie Black projecting the words “Slaves Lived Here” on the house. All historic houses must grapple with this balance of offering a look into the past while conveying the fuller story of their histories, often with limited staff and space.

Located between the Brooklyn neighbourhoods of East Flatbush and Canarsie, the Wyckoff House has approached this challenge by shifting the focus from the house itself to its community. Built in 1652, it is the oldest house in the city, dating to when this area was farmed by Dutch colonists—it is currently wedged between a car wash and a McDonald’s. The steep slope of its roof faces the now-obsolete Canarsie Lane, which was once a Lenape hunting path. As Melissa Branfman, the executive director of the Wyckoff House, observes: “This land has had many lives, and to interpret it only from the life of the Dutch family that lived in the house is very limiting.”

The Wyckoff House does not have interpretive panels or roped-off exhibition spaces; visitors are immersed in rooms where plants from its garden are dried for tea, much like they were in the 17th century. Its outdoor space has allowed the house to be decentred in its stewardship, with the land it sits on hosting festivals celebrating the Caribbean culture of its Brooklyn community, and its farm growing crops such as pigeon peas that are common in Caribbean food but can be hard to find in the borough.

“That kind of interpretation can make parallels between liberation and colonial culture that were happening both in the Americas, like in New

Netherland, as well as other countries, where some of the Caribbean was under Dutch rule,” Branfman says.

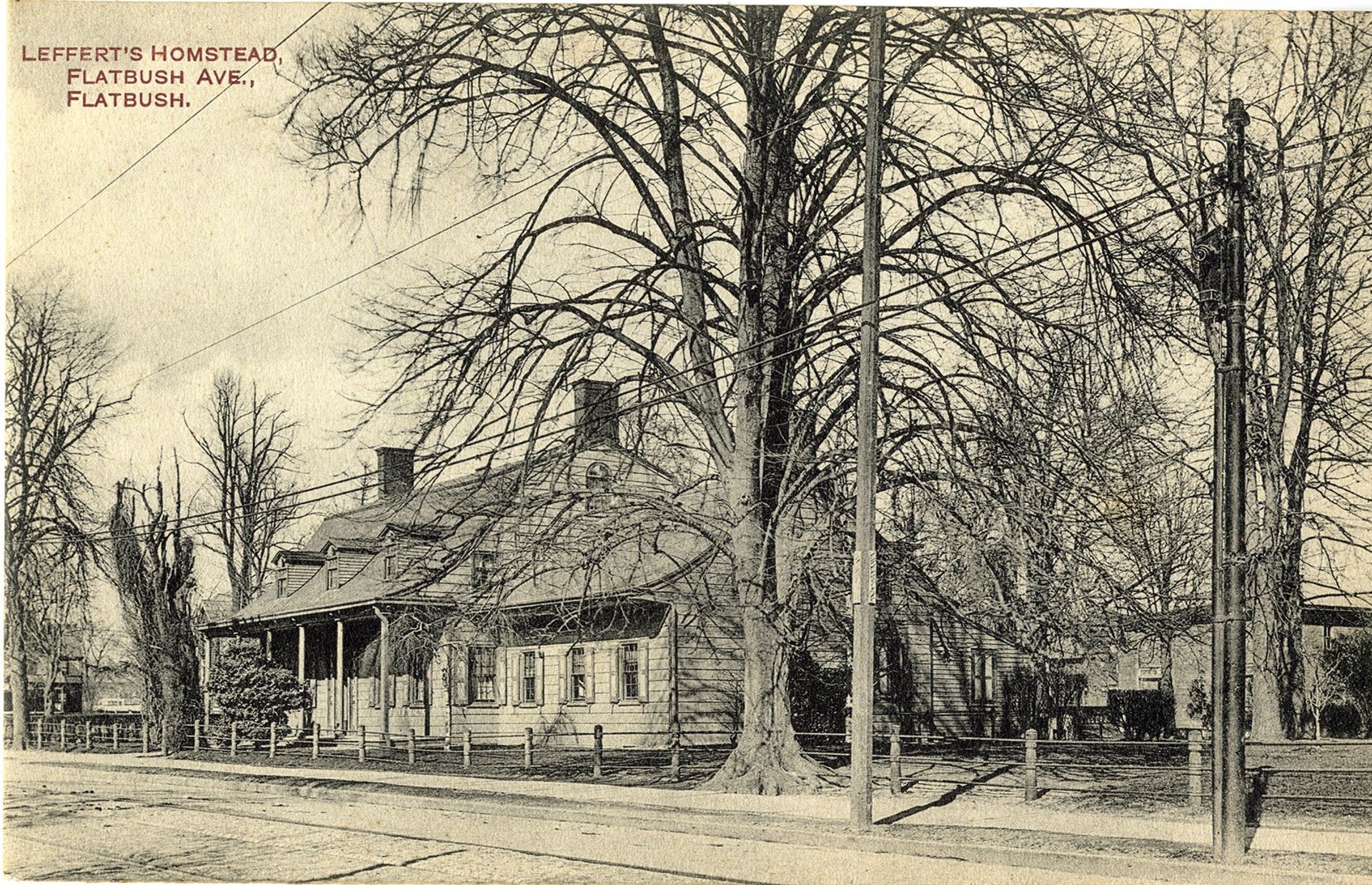

A postcard (around 1900) of Lefferts Homestead at 563 Flatbush Avenue, before it was moved to Prospect Park in 1918 © Prospect Park Archives/Bob Levine Collection

A more inclusive history

The Lefferts Historic House, located at the edge of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, is likewise being re-examined for how it can present a more inclusive history. It dates to 1783 and includes wood salvaged from a 17th-century house, reflecting the Dutch influence that endured under English rule, with its Dutch colonial frame house including a broad porch lined with columns facing the busy traffic of Flatbush Avenue. A new initiative from Prospect Park Alliance is elevating the past four centuries of resilience of the Lenape and people of African descent, while a $2.5m architectural restoration is protecting the site for the years ahead.

“Maintaining a nearly quarter-century-old house takes an enormous amount of money, time and work, much of it unseen by the public,” says Dylan Yeats, a project manager for the house. “So in addition to developing interpretations with our ReImagine Lefferts initiative, Prospect Park Alliance has been investing in the structure itself.”

The Lefferts Historic House closed in 2019 for the overhaul and will be reopening this summer. When it debuted as a museum in the 20th century—after being relocated to the park in 1917 to protect it from development—it concentrated on the Lefferts family. The house will welcome visitors later this year with a textile installation on its façade by the artist Adama Delphine Fawundu that honours the 25 identified people who were enslaved by the family between 1783 and 1827.

“It can be very easy to forget the past in a city like New York that is constantly remaking itself,” Yeats says. “Historic houses and other markers of the past offer visitors and even passers-by an occasion to remember. Many Brooklynites don’t know the colonial history of the land they live on or what those who came before them did on the land.”

Surviving the odds of New York’s continuous development, these houses convey part of the story of how the largest city in the US grew from a small colony at the tip of Manhattan. Their preservation also recalls how practices like slavery, associated more often with the American South, were foundational to the city.

“It’s an exciting time to be interpreting history and talking about history, because I’ve definitely seen a shift in the field, which is less about telling a singular narrative,” Branfman says. “We’re starting to realise that the facts that we know are often not all the facts. And if you look through the same materials with different eyes, you might find different things.”