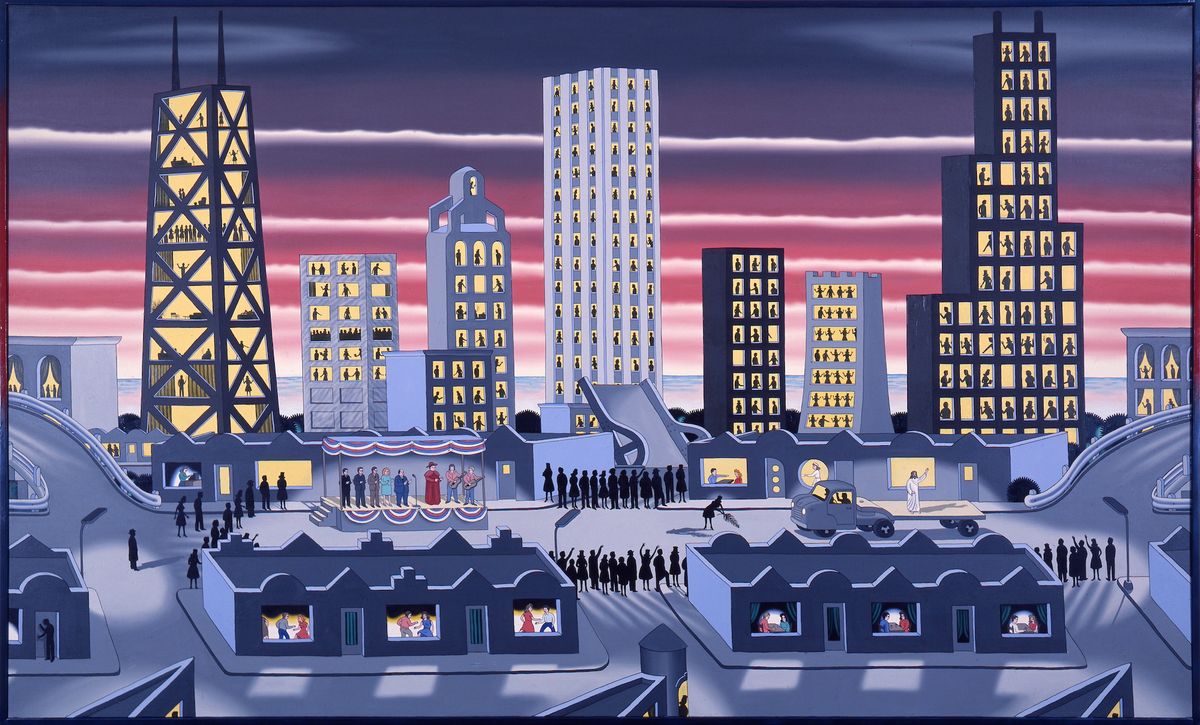

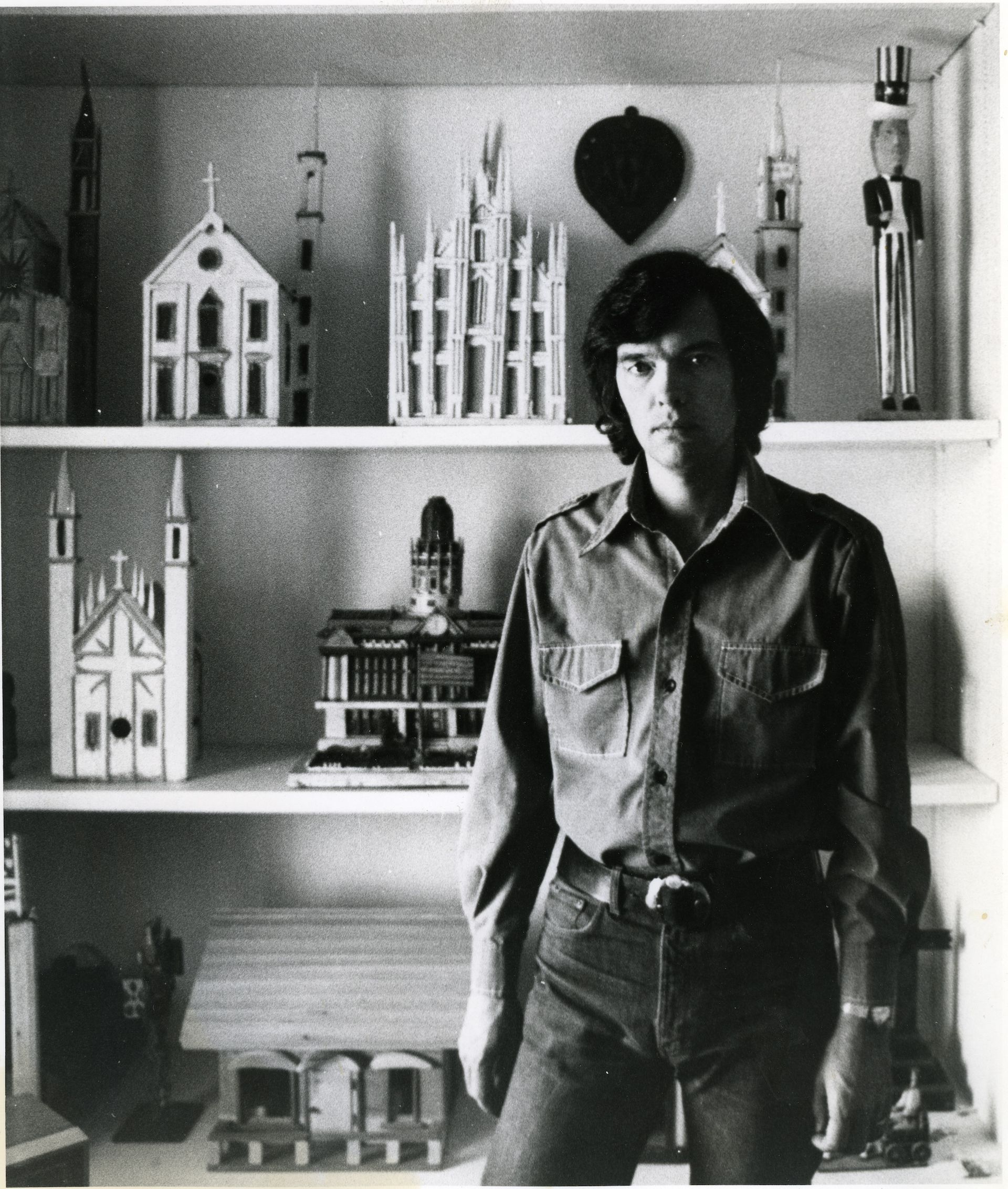

Roger Brown (1941-97) is best known as a painter whose carefully modelled imagery— of leaning skyscrapers, scalloped clouds and the occasional chicken-shaped building—held a warped mirror to scenes of urban solitude and suburban sprawl. But he was also an impassioned collector of art and objects that informed his creative work. He transformed the home he shared with his partner George Veronda in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighbourhood into a museum packed with folk art, curiosities, works by self-taught artists, costumes and pieces by contemporaries like Christina Ramberg, Karl Wirsum and Jim Nutt, all hung salon style across its densely packed walls.

In 1997, the home became the Roger Brown Study Collection, a museum and archive in an 1888 storefront building that at various times housed a tobacconist, a bookbinder and a plastics manufacturer. Brown sold the home and donated his collection to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) in 1996, one of many gifts to the school he made towards the end of his life, which also included properties in California and Michigan, the latter of which now serves as an artist residency for SAIC faculty. The estate of Brown’s paintings and prints is jointly administered by Kavi Gupta Gallery and SAIC, and sales partially support the upkeep of the collection.

Portrait of Roger Brown in his Chicago home in 1975, by Bill Bengtson. Courtesy of the Roger Brown Study Collection of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

“Roger viewed the intended audience for his collection as artists and anyone interested in art,” says Melanie Emerson, the dean of the library and special collections at SAIC, which oversees the space. The house

museum as a creative lab has been the work of generations of SAIC students, who have done everything from building databases of its original sketchbooks, personal correspondence and other collections, to

undertaking historic preservation projects involving the building, says Emerson. Most first-year students visit the collection for their classes.

The collection has been closed since March 2020, when it shut its doors at the onset of Covid-19—an occasion marked on its blog with an image of an item in the collection, a hand-painted sign that reads: “WOMAN 104 YRS OLD SAYS, STAY HOME, MIND YOUR OWN BUSINESS.” Now the collection is undergoing long-planned renovation work and is set to reopen at the end of 2024 or early 2025, according to James Connolly, the collections manager. Brown shared an interest in collecting with many of the Imagists, a loose group of Chicago artists who rose to prominence

in the 1960s for their wacky takes on folk art, Surrealism and vernacular culture. All of the Imagists studied at SAIC, and many went on to teach at the institution. As a student of the painter Ray Yoshida and the art historian Whitney Halstead, both of whom championed self-taught artists, Brown shared a collecting philosophy that embraced fl ea-market fi nds and mass media as much as it did contemporary art.

This approach shows up in Brown’s curation as well: there is no separation in terms of region, or divisions between his fellow art school-educated contemporaries and the self-taught artists and craftspeople

(some named, some anonymous) he collected. One sitting room is hung with 36 drawings by Joseph Yoakum, the visionary landscape artist whose influence is palpable in Brown’s own paintings.

“He was most interested in work by artists who similarly created deeply

personal, self-expressive work, rather than work that followed the most recent art world trends,” Emerson says.

Shelf in the Roger Brown Study Collection. Photograph by James Connolly. Courtesy of the Roger Brown Study Collection of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

In a nod to the sensibility of its founder, the Roger Brown Study Collection even includes two free gift shops, of sorts, founded by former curator Lisa Stone. The dishwasher houses greeting cards of Brown’s works, and visitors can take home or donate objects of interest to the garage, which still has the artist’s Ford Mustang parked inside. The inspiration for the latter was the still-extant Maxwell Street Market, a century-old Chicago flea market that Yoshida encouraged his students to visit, and which was the source for many of the objects in the collection.

Brown wrote of the objects he had amassed: “I feel the things in the

collection are of universal appeal to all artists and people with a sense of the spiritual & mystical nature that material things can evoke.”

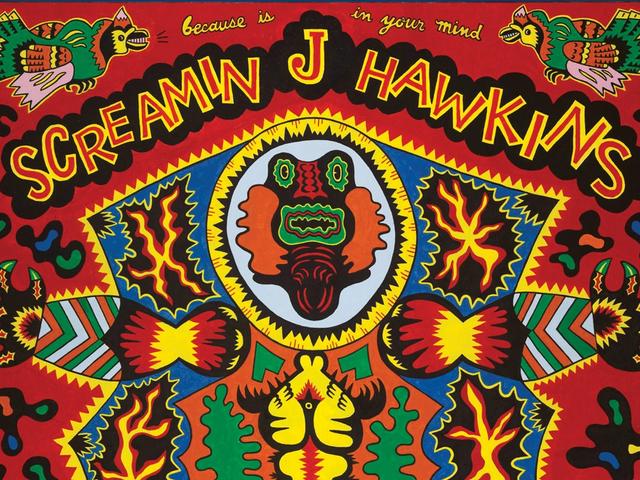

Seven miles away, in the Jefferson Park neighbourhood on Chicago’s Northwest Side, a different institution is working to steward the legacy of a fellow Imagist painter, Ed Paschke (1939-2004). Paschke was known

for his fluorescent paintings combining pop culture imagery in an otherworldly chiaroscuro, with subjects including runes, hands and figures (from burlesque dancers to Shakespeare) covered in delicate acid blotter patterns of pinstripes and dots.

Studio with a story

The Ed Paschke Art Center (EPAC) was founded in 2014 by the Rabb Family Foundation with the support of the artist’s family, and includes a collection of his works, space for rotating exhibitions by living Chicago artists and a re-creation of Paschke’s studio, a former dentist’s office in Rogers Park that he worked in for more than two decades.

“I preserved the studio and insisted on a recreation of it because it was the essence of the artist,” says Marc Paschke, the artist’s son, who is the co-director of the Ed Paschke Art Foundation, which manages the artist’s

estate. “Without experiencing it, my sister and I both felt you really couldn’t fully understand what our dad was about.”

A re-creation of Ed Paschke's studio at the Ed Paschke Art Center in Chicago Courtesy the Ed Paschke Art Center

After Paschke’s death in 2004, the decision to open a new space devoted to him and his vision of championing Chicago artists, rather than work with a pre-existing institution, seemed like the only way to move forward, according to Lionel Rabb, EPAC’s co-founder and co-director.

“In all honesty, in the art community and the art institutions, outside of holding a couple retrospectives, they haven’t done anything,” says Rabb, a collector, businessman and philanthropist who has supported numerous projects in Jefferson Park. Although Rabb never met Paschke, he takes seriously Paschke’s vision as an educator and proud Chicagoan, which also shaped the centre’s mission.

“He seemed like a really hard-working, blue-collar guy who wanted to create access to world-class art,” says Rabb, so it was important to situate the centre in a working-class neighbourhood, rather than in downtown Chicago.

Paschke was born in Chicago and grew up mainly on Chicago’s Northwest Side. After receiving his bachelor’s degree from SAIC, he worked as an illustrator for Playboy magazine and later served his military draft by illustrating instruction manuals. After an assortment of odd jobs, including working on a map for training astronauts on the Apollo moon mission, Paschke became a professor at Northwestern University, where he taught at for 26 years.

Rendering of the future Ed Paschke Art Center expansion Courtesy the Ed Paschke Art Center

His generosity to students and other artists also informed the mission of EPAC, according to Rabb. “All through his career, but even at the pinnacle, before he died, if you had a show, and the news wanted to come interview Ed, he would say, ‘Oh, meet me over at [some other artist’s] show, and I’ll talk to you there,’ and he would do that to support you. He would talk about himself for a minute, but then he would talk about you. That was a story we heard over and over,” Rabb says.

EPAC has also been closed to the public since the onset of Covid-19 in early 2020, and it is unclear when it will reopen. Rabb says he hopes to have a clear idea later this spring. A zoning change passed in 2023 cleared the path for the centre’s expansion, a project that includes a new and larger exhibition space, offices and an educational area. Located near the Sullivan Chicago Studio of Performing Arts and the National Veterans Art Museum, of which Rabb is the board chair, EPAC is part of the planned Northside Cultural District.

In the meantime, the institution continues to host an annual all-ages event, Paschke in the Park, on 11 June, the artist’s birthday, and they have also created Ed Paschke colouring books that have been placed in Chicago public libraries and park district spaces.

Paschke said of his work, “They either love it or hate it, but rarely are they indifferent to it.” With community outreach and inventive programming, EPAC guarantees the former.