Refik Anadol has worked at the heart of a series of breakthrough technological developments in the past 15 years on his way to becoming one of the world’s most visible and thoughtful digital artists. He has created with algorithms since 2008; with projection mapping on an architectural scale since 2010; in virtual reality since the days of the Oculus developer kit in 2013; with artificial intelligence (AI) for a decade; with an artist residency with Google Artists and Machine Intelligence (AMI) in 2016, when he started AI data painting and making AI data sculptures; and with the blockchain and NFTs (non-fungible tokens) since 2020.

With his exhibition Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive, at Serpentine Galleries in London, Anadol makes an arresting mark on two emerging trends in digital art (Anadol prefers to describe his own work as media art): for showing the artist’s process, in order to demystify AI, NFTs and other acronym-rich technologies; and for using artificial intelligence to democratise information. Both trends have the intent of reducing fear of the technological “unknown”, and of demonstrating, to the traditional art world, the serious intent of digital artists. The exhibition is, Anadol tells The Art Newspaper, the first time that his studio has demystified “all our resources, [to show] where our data comes from. And that's a big change”.

Anadol is one of the featured artists in the “On Process” chapter of the recently published On NFTs (Taschen, 2024), a scholarly 600-page survey of a decade’s developments in the world of NFTs edited by the writer and artist Robert Alice. The project whose process Anadol analyses is his Living Architecture: Casa Batlló (2022), a media art piece on Antonio Gaudí’s 1906 house in Barcelona created by using AI to model a dataset based on millions of publicly available images and documents relating to the house. Anadol and his team projection-mapped the work on to the façade of Casa Batlló in May 2023, using the output from the AI model to “hallucinate”, as Anadol puts it, on the architecture of the building before a live audience while running the piece in parallel at Rockefeller Plaza in New York City.

In the section of On NFTs on Living Architecture, each step in the creative process is listed: from collecting a dataset made up of Gaudí’s sketches, files from visual and academic archives and publicly available images of the house; to processing this data to detect objects and classify images; to sorting the data into themes; to generating an AI model to be trained through processing the archive. All this comes before creating a “pigment pipeline” from the visual archive to feed into the final output, expressed in the swirling, fluid-inspired movements that have been a signature of Anadol’s work for the past decade and more.

The Serpentine data process wall

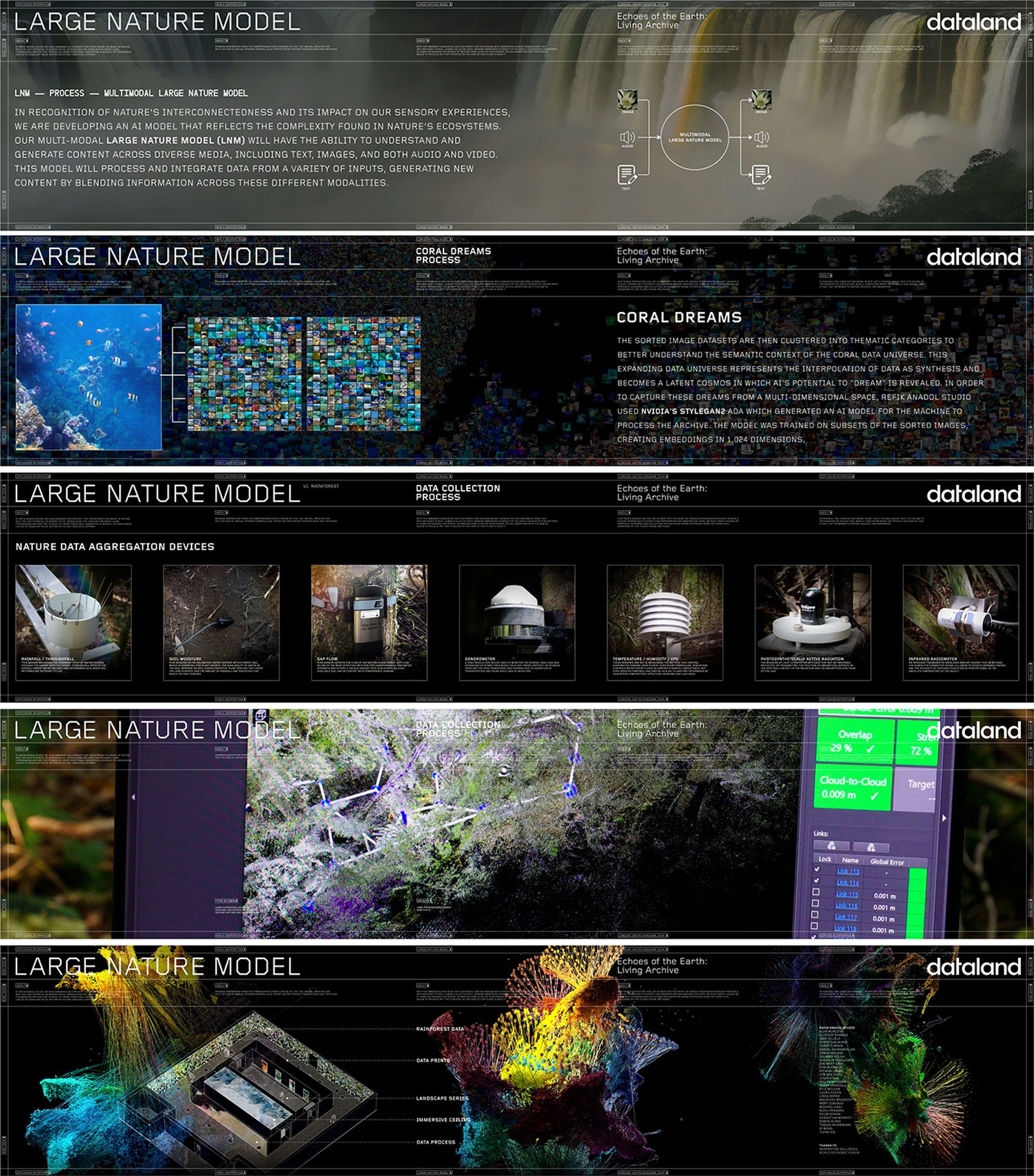

Process is the first thing the visitor encounters at the Serpentine when entering Anadol’s Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive. On a long, letter-box-shaped, data process wall at the front of the exhibition, text and diagrams play in a 30-minute loop to explain how the artist has gone from raw data to finished, AI-powered video output, in which massive data sets of under-sea coral and the Amazon rainforest—built from audio, text, image and video data shared by global academic institutions—have been classified and themed into what Anadol calls a Large Nature Model (LNM). It is, Anadol says, the world’s first open-source generative AI model dedicated to nature, one whose algorithms are trained on “nature’s inherent intelligence” rather than the human intellect. It is, he tells The Art Newspaper, “a living archive, a living work”. There are two datasets from the LNM at play in the Serpentine show: Artificial Realities: Rainforest and Artificial Realities: Coral.

"Showing the ingredients of the medium": sample images from Refik Anadol's data process wall at Serpentine Galleries, London, that introduce the Large Nature Model (LNM) (top), explain the thematic cataloguing of images from institutional archives, describe approaches to aggregating ecological data in nature and show the layout of the show with an isometric model of the gallery Refik Anadol, Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive, 2024. Courtesy Refik Anadol Studio and Serpentine

Anadol had been mulling on the LNM for eight years, inspired by his long-standing collaboration with the Yawanawa Indigenous people in Brazil, who he regards as his mentors in the project. "When I asked the Yawanawa family what do you think about AI, they said, it's not a surprise for us. We live in nature. Nature is our AI."

During the Covid-19 lockdown of 2020-21 he approached some of the largest public archives of natural history data to ask for their help. The narrative on the data process wall—which comes under Anadol’s umbrella project, Dataland, a “museum and Web3 platform dedicated to data visualisation and AI arts”—lists the participating institutions who answered his call. They include the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, holders of 148 million objects, 9 million public specimen records and 6.3 million public images; the Natural History Museum in London, which has 80 million specimens and 4 million public images; the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, in New York state, which holds 54 million images, 2 million sound recordings, and 255,000 videos; the crowd-sourced iNaturalist, home to 181 million images; the data aggregation platform Encyclopedia of Life; and herbarium and botanical gardens collections in Paris, New York, Harvard, Rio de Janeiro and other cities.

Anadol and members of his studio team have collected data of their own, filming and 3-D scanning, while also gathering information on rainfall, soil moisture, light and object temperature, in 16 locations worldwide including Amazonia, Australia and Indonesia. There is a special section in the data process wall on birdsong, and how audio files from the Macaulay Library at Cornell were tagged to extract audio signatures, with a specific emphasis on Amazonian species.

As part of demonstrating process, Anadol displays arrays of some of the millions of source images that his Large Nature Model is trained to turn into text-to-image generative video Refik Anadol, Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive, 2024. Installation view, Serpentine North. Photo: Hugo Glendinning. Courtesy Refik Anadol Studio and Serpentine

The video outputs from Anadol’s model play out in wide-angle projection mapping. The moment of the AI model's “dreaming” with its data set is compellingly represented by great video flights of digital images of coral, rainforest and beyond, massing and soaring like a murmuration of starlings—a technique Anadol also used when exploring a data set built from the archives of the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2022-23 for his piece Unsupervised. At the Serpentine, as at MoMA before, these rushing clouds of raw images act as a visual metaphor of the data being fed into the AI modelling process. To become part of the final “data sculpture” video.

AI adapted to architecture

Anadol has long been concerned with how his AI pieces engage with architecture, using it at once as canvas and container. At MoMA, he showed Unsupervised on one massive screen, slightly taller than square, designed to fit the dimensions and character of the double-height Gund Lobby. At Serpentine North, he works with the gallery’s long and low proportions with a wall-covering screen on each of the three main walls. He is delighted that visitors to the show, some of whom stay for an hour or more, have asked the gallery to install benches so that they may meditate at length on the wide-angle generative video output, in which Anadol shows three aesthetics: his studio’s signature highly textured fluid dynamics; a new hyper-real video style; and a new dreaming, sci-fi-cinema-like, aesthetic which, with the Rainforest data set, produces fantastically scaled and detailed plants, trees and undergrowth.

Levels of process: in one of the smaller crosswalk spaces at Serpentine North, screens face each other in pairs, showing the AI model’s output in two aesthetics, in parallel. On the left, the model is run with a hyper-real aesthetic new to Anadol's generative video work, while, simultaneously, on the right-hand screen, it dreams with the same data in classic Anadol textured, fluid-dynamic style Refik Anadol, Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive, 2024. Installation view, Serpentine North. Photo: Hugo Glendinning. Courtesy Refik Anadol Studio and Serpentine

Playing with these three aesthetics gives Anadol the chance to show another level of process in the crosswalk spaces that run between the main galleries at Serpentine North. In one of these spaces, video is projection-mapped on the ceiling—to Anadol, AI is “all about shifting perspectives”—while in the second, a sequence of portrait-shaped screens, at human scale and facing each other in pairs, show the AI model’s output in two aesthetics in parallel. On one screen an exotic bird or Amazonian plant might be generated in hyper-real style, while, simultaneously, on the facing screen, the AI model works with the same data in classic Anadol textured, fluid-dynamic style.

“To me it is a super exciting time to be working,” Anadol says. “Not only inventing a medium, but showing the ingredients of the medium.”

The democratisation of data

Anadol’s LNM is open-source, allowing the data-contributing institutions or interested creatives or researchers to run instances of the model to create output of their own. Anadol has been excited by how many student and school inquiries the show has provoked, asking largely about the challenges of creating a project on this scale.

“It's super important,” Anadol says, “that in a world where everything is becoming closed source, the show is open-source. It is an important message, very strongly stating that the future of AI cannot be only closed source.” He sees the piece as “Democratising data, demystifying AI and contributing something bigger than us”. It is text-to-video AI research, he says, that enables him to create, much like OpenAI’s Sora model. It is very similar, he says, but open-source.

Nature in and around Serpentine

Anadol’s hosts at Serpentine Galleries—an institution that Anadol has been associated with for a decade, with its director, Hans Ulrich Obrist, being one of his earliest mentors— have recently placed process at the heart of Future Art Ecosystems 4: Art x Public AI (Fae 4), the fourth annual report from their Arts Technologies team designed to encourage new thinking and collaboration around the interaction between art and technology.

The report encourages cultural organisations to unite in discovering their own data sets and how to make use of them, using AI, in coming months and years. The process the report focuses on is demonstrating the software and hardware tiers that go into creating what it terms "public AI" for the public good.

At the opening of Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive, Anadol and Obrist spoke of their shared excitement at bringing nature in the form of the LNM into a gallery which is at the heart of Hyde Park’s 350 acres of grass, lake, trees, bird and animal life. “It’s a perfect place to unveil the first step,” Anadol says. “It's free and open.” But the piece, he says, “is not about replacing nature. It's about loving, respecting and remembering nature.”

“All about shifting perspectives”: In one of the smaller crosswalk spaces at Serpentine North, video output is projected on the ceiling—bean bags provided Refik Anadol, Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive, 2024. Installation view, Serpentine North. Photo: Hugo Glendinning. Courtesy Refik Anadol Studio and Serpentine

Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive shows Anadol to be once more in step with the artistic and technological times, while still looking to take the next stride forward. In its new aesthetic approaches, the piece builds on what Anadol showed in Unsupervised when working with generative AI to painterly effect, using an algorithm designed to allow a cumulative, accidental, beauty by categorising and riffing on MoMA's abundant museum archive.

The inquisitive ambition and energy of Echoes of the Earth—with its meditative and often mesmerising revisualisations of Amazonian rainforest and under-sea coral beds, alternately hyper-real and deep-dreaming—is such that the work sometimes appears to be half-bursting over the edges of the gallery's screens, as if willing itself out into the surrounding parkland, and on to future installations of this thoughtful and thought-provoking experience.

Anadol sees his Serpentine show as the first iteration of his LNM; a “very site-specific intervention. turning the building into an archive”, and a canvas. “It’s not the first and final piece,” he says, “it’s evolving.”

- Refik Anadol: Echoes Of The Earth: Living Archive Serpentine North Gallery, London, until 7 April