Growing up in rural Romania, Constantin Brâncuși (1876-1957) learned how to carve wood before he taught himself to read and write. After a classical training in sculpture in Craiova and Bucharest, legend has it that the ambitious young artist crossed Europe on foot to reach Paris, the capital of Modernism, in 1904. Handpicked by Auguste Rodin as a promising apprentice, he quit the master’s studio after a month because, as he later put it, “nothing grows in the shadow of a tall tree”. The rest is art history. Brâncuși abandoned modelling in clay, Rodin’s primary technique, for the direct carving of startlingly simplified, near-abstract forms in wood or stone: a breakthrough that reshaped the course of sculpture in the 20th century.

Brâncuși “totally transcends the various movements and -isms of Modern art”, says Ariane Coulondre, the lead curator of the Centre Pompidou’s major survey exhibition devoted to the artist this spring. Preferring to work alone, he rarely had pupils (Isamu Noguchi was a notable exception), and yet generations of artists took the seeds of his practice forward into their own. “Although not abstract himself, Brâncuși paved the way for abstract sculpture,” Coulondre says. The Minimalists inherited his concerns with seriality and spatial relationships. Brâncuși’s legacy remains “palpable” in contemporary works by artists as diverse as Jeff Koons, Pierre Huyghe and Simon Starling.

Brâncuși’s Bird in Space (1941). A whole flock of his Birds will be on show in Paris

© Succession Brancusi. (Adagp). Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Dist. RMN-GP. All rights reserved

Yet for all his towering influence, large-scale exhibitions of Brâncuși’s work have been few and far between. This is partly because the sculptures are “extremely fragile and difficult to move”, Coulondre says. Perhaps it is also a result of Brâncuși’s exacting vision for his work—in life and in death. His output was relatively small, obsessively circling a core of favoured motifs in pursuit of perfection: the kiss, a sleeping head, a bird in flight. In 1956, a year before he died, he bequeathed the contents of his studio to the French state on the condition that the ensemble be preserved exactly as he had left it.

Frozen in time, the dense display of 137 sculptures and 87 custom pedestals has been housed at the Centre Pompidou for almost half a century. In the 1990s, Renzo Piano designed a dedicated annex for the replica studio, opposite the main museum building. Only now, as the Pompidou prepares for a five-year closure and renovation in 2025, can it dismantle the studio and present the objects anew. (The annex closed last autumn, allowing some works to travel to a Romanian homecoming exhibition in Timișoara ahead of the Pompidou’s show.)

This is “an exceptional opportunity” to show the entire scope of Brâncuși’s art, Coulondre says, “demonstrating the continuity between all his creative fields”. The exhibition includes more than 120 sculptures alongside 200-plus drawings, photographs and films. At its heart is the studio, “a captivating space essential for comprehending his creative process”.

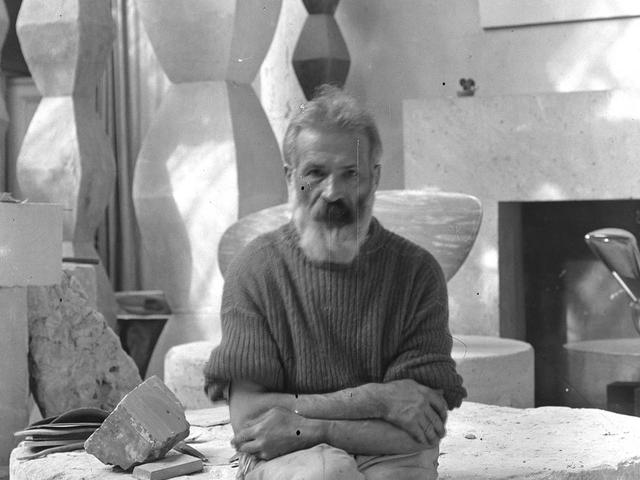

The exhibition designer Pascal Rodriguez has conceived a “white and luminous” first gallery that aims to “convey in a physical way the shock felt by visitors” to the extraordinary environment Brâncuși created in the Impasse Ronsin, a Montparnasse artists’ colony. Man Ray recalled being “more impressed than in any cathedral”, while Ezra Pound described the studio as a “whole universe of form… a system”. For four decades, it was the workshop where Brâncuși chiselled stone, carved wood and cast bronze, and the home where he entertained friends with parties and steak dinners.

Art or taxable utensil?

Later in life he became “reluctant” to exhibit anywhere else, Coulondre says, bruised by the “virulent reactions” his radical sculptures provoked. The scandals included a court battle with US customs authorities over whether a highly abstracted bronze Bird in Space was a duty-free work of art or a taxable utensil. Brâncuși and his avant-garde supporters eventually won the case in 1928, when the judges grudgingly recognised art’s new potential to “portray abstract ideas rather than imitate natural objects”.

A century on, a whole flock of soaring Birds in Space will be an exhibition highlight, Coulondre says, installed in front of the Paris skyline on the Pompidou’s sixth floor. Brâncuși’s infamously phallic Princess X, which was withdrawn from the 1920 Salon des Indépendents for obscenity, will have pride of place in a section devoted to the artist’s merging of feminine and masculine figures.

Brâncuși’s Léda (1926) © Succession Brancusi, All rights reserved Adagp; Paris 2024 Photo: Centre Pompidou; Mnam-Cci, Georges Meguerditchian, Dist. Rmn-Gp /Dist. Rmn-Gp

The thematic hang will be at once “sober” and “lively and joyful”, according to Coulondre. The same duality could be observed in Brâncuși’s own view of his sculpture. “My sculptures are not intended to command respect,” he said. “They are to be loved and played with.” The Pompidou will mount a bronze Leda on a spinning pedestal, as Brâncuși had it in the studio, so as to admire the play of light and reflections across the metal surface.

Outwardly simple, Brâncuși’s sculptures gave form to profound ideas. Leda, a new twist on Ovid’s ancient myth, captured metamorphosis. Endless Column, the centrepiece of the exhibition’s final gallery, suggested the infinite possibilities of art itself. Brâncuși extrapolated a modest wooden plinth into a monumental pillar that could, at least in theory, unite heaven and earth. It remains “a powerful metaphor for the ever-renewed creative act,” Coulondre says. “As Brâncuși wrote: ‘I can start something new every day, but how can I finish?’”

• Brâncuși, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 27 March-1 July 2024