Several attendees during the 12 March press preview of the 2024 Whitney Biennial—Even Better Than the Real Thing (20 March-11 August), curated by Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli—remarked on how understated this edition of the exhibition is, particularly compared with the 2017 and 2019 iterations that were rocked by controversies and protests. It is so understated, it seems, that one of its most pointed comments on current events went largely unnoticed, including by Iles and Onli: a large-scale neon work by the artist Demian DinéYazhi’ that occasionally flickers with the words “free Palestine”.

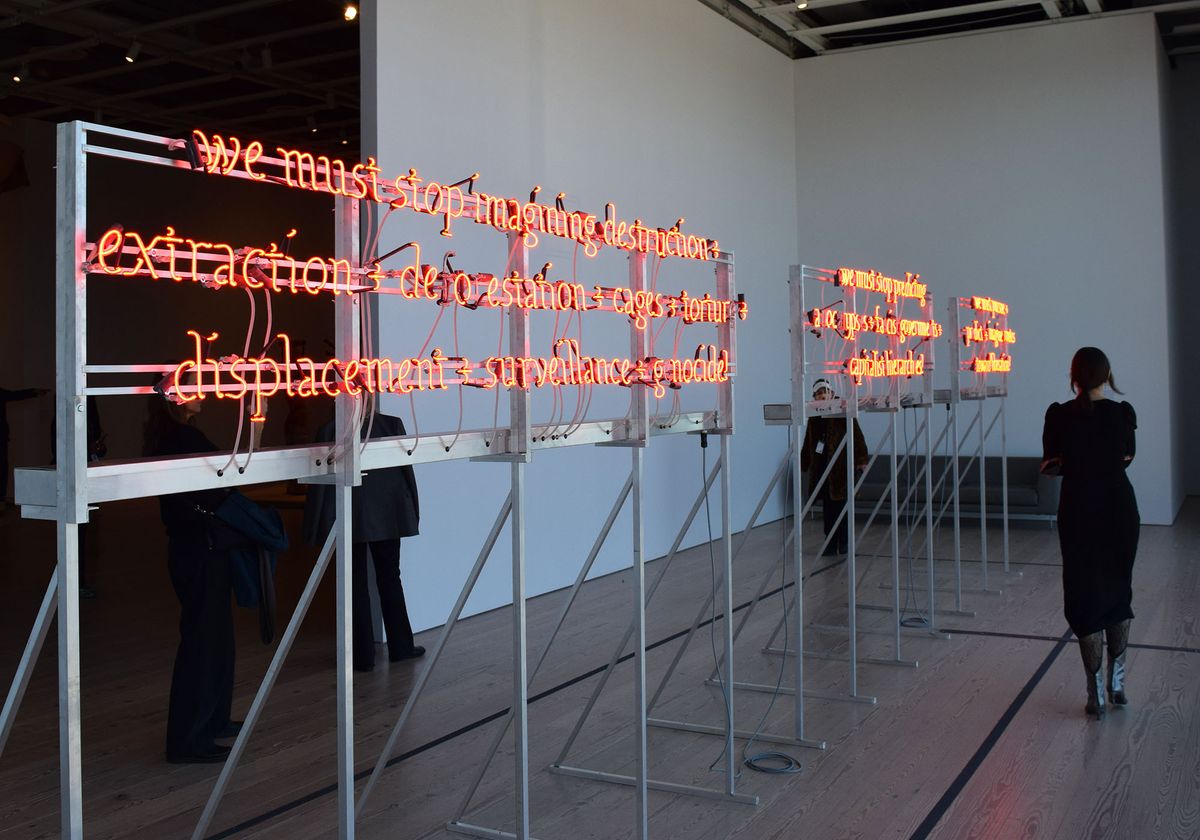

DinéYazhi’, who is a member of the Diné clans Naasht'ézhí Tábąąhá (Zuni Clan Water's Edge) and Tódích'íí'nii (Bitter Water) and is based in Portland, Oregon, premised the work on three stanzas of political poetry they composed before the events of 7 October 2023 and the Israel-Hamas war. The neon, titled we must stop imagining apocalypse/genocide + we must imagine liberation (2024), is installed facing a wall of windows overlooking the West Side Highway and the Hudson River. It is typical of what art historian Josie Roland Hodson describes in the biennial catalogue's entry for DinéYazhi’ as their “practice of decolonial resistance and institutional critique”.

Most of the time, the work’s illuminated text encourages viewers and readers to stop envisioning worsening, apocalyptic conditions and to instead “pursue + predict + imagine routes toward liberation!”. Seemingly sporadically, a smattering of letters across the three stanzas of neon text spell out "free Palestine".

The fleeting political statement was first reported by Artnet News, and a Whitney spokesperson confirmed to The New York Times that the museum was unaware of it: “The museum did not know of this subtle detail when the work was installed.” The spokesperson added: “The Biennial has long been a place where contemporary artists address timely matters, and the Whitney is committed to being a space for artists’ conversations.”

The artist told the Times the work was inspired in part by their friend Klee Benally, a Diné activist who died in December, adding: “The piece in its final form and as it currently exists today is a response to being situated within settler colonial institutions.”

Artists making works that appear to address the Israel-Hamas war and the institutions showing them have frequently come under pressure, resulting in the cancellation of exhibitions, residencies, public programmes and more, often followed by a backlash of artists and lenders withdrawing works or institutional leaders stepping down in scandal, protest or solidarity. Many observers of the art world are turning their eyes to the Whitney to see what more may transpire now that DinéYazhi’'s gesture has been revealed.