Entangled Pasts, 1768–now, and the exhibition it accompanies, might be considered a landmark—a beacon, even—in a growing landscape of publications, exhibitions and debates working to challenge art’s colonial histories. As its title indicates, the histories it unpicks are entangled with the history of the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) itself, since its foundation in 1768 by a group of 34 British, Irish, European and American-born artists led by Joshua Reynolds.

In their introduction, the exhibition curators Dorothy Price (professor of Modern and contemporary art and critical race art history at the Courtauld Institute of Art) and Sarah Lea (curator at the RA) begin by asking the pointed question: “What does it mean for the Royal Academy to stage an exhibition in 2024 that reflects on its role in helping to establish a canon of Western art history within the contexts of British colonialism, empire and enslavement?” In relation to this, and responding to the different roles of the RA, the authors then quote the writer and poet Audre Lorde: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”. And yet, this book, in a sense, does just that, reading against the grain of established histories of the RA, and therein lies its value. That in itself is difficult to achieve with any degree of integrity and sensitivity, particularly given the complexities of untangling and exposing, without gloss, what has remained hidden in those histories, while also avoiding the pitfalls of recreating spaces of trauma. The approach here, and in the exhibition, is to bring historic and contemporary works together, the latter unravelling the former in ways that appreciably deepen and enlarge an understanding of Britain’s colonial history.

Interrogation of empire

Extensively and lavishly illustrated, Entangled Pasts falls broadly into two parts: four essays, including the introduction, and a catalogue—which structures clearly the material—followed by a section of short biographies of artists and sitters that is critical to an understanding of the arguments and positions presented by Price, Lea and the other authors, Alayo Akinkugbe, Esther Chadwick, Cora Gilroy-Ware and Rose Thompson. The catalogue is divided, in turn, into three thematic sections, each with two or three short essays. The themes “Sites of Power”, “Beauty and Difference” and “Crossing Waters” cleverly allow the authors to approach their interrogation of empire, colonialism and art in a truly innovative fashion that supports the opening up of questions while, at the same time, lending a cohesiveness to the material that makes for hugely compelling and informative reading.

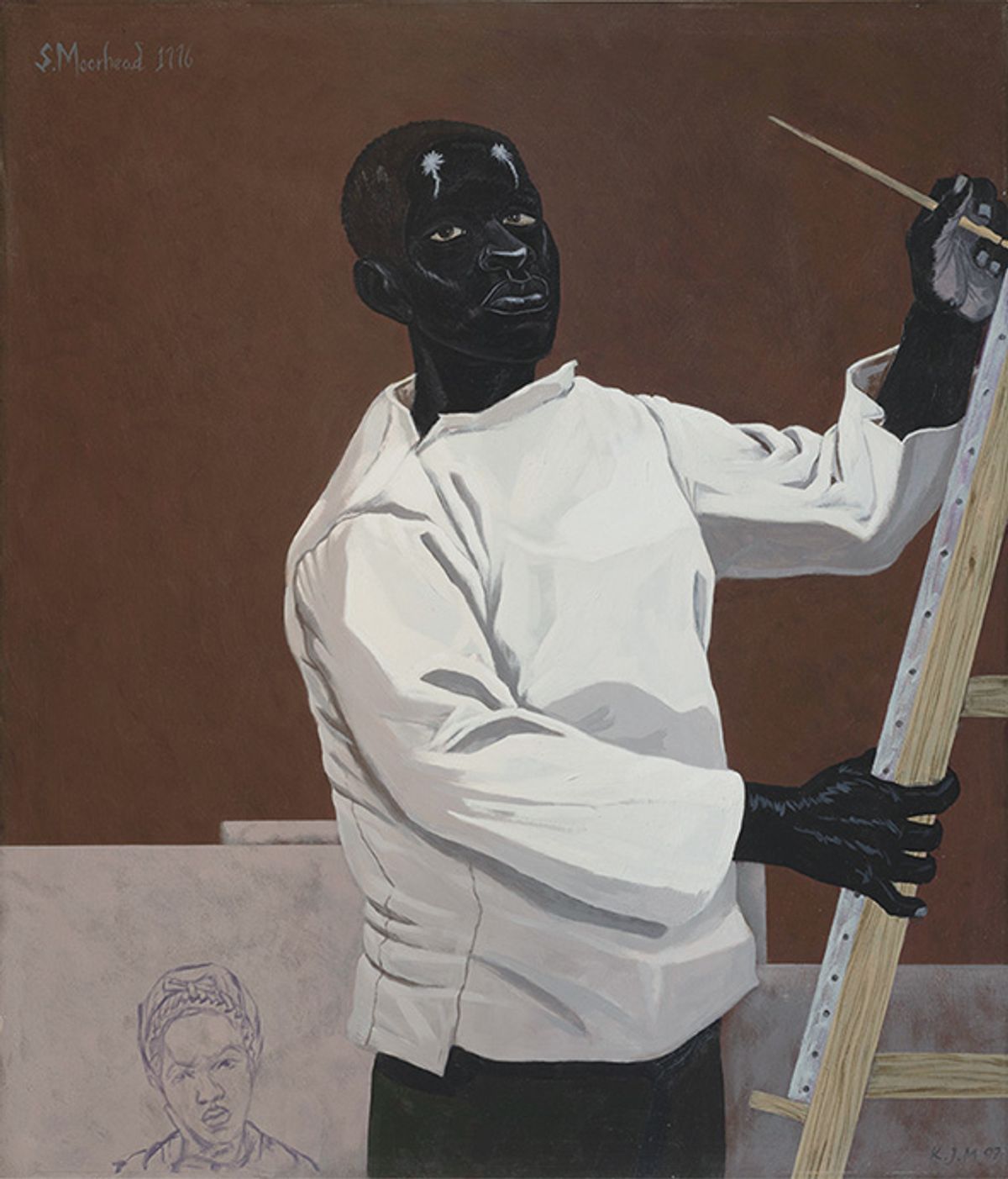

Within the theme of “Sites of Power”, for instance, Lea considers the slippage between a portrait and the portrayal of a more generalised “type”, and the problem of erasure. In 1773, Phillis Wheatly was the first African American to publish a book of poetry, one poem dedicated to the painter “S.M.”, assumed to be Scipio Moorhead, none of whose work survives. Now, the painter Kerry James Marshall gives a face to Moorhead in the painting Scipio Moorhead, Portrait of Himself, 1776 (2007).

Enslavement, conflict, luxury consumerism and cultural exchange are unpicked through the lens of India’s historic textile trade

British colonialism was founded on shipbuilding and navigation, and Hew Locke’s installation Armada (2017-19) recalls ships from different times and places. In this space, yesterday’s refugee may be a citizen of the present day. Royal Academicians, including Edward Penny, the RA’s first professor of painting, benefited from the patronage of the East India Company (1600-1874). In a contemporary examination of such relationships, The Singh Twins unpick enslavement, conflict, luxury consumerism and cultural exchange through the lens of India’s historic textile trade in their “Slaves of Fashion” series, including Indiennes: The Extended Triangle (2018).

For the book’s second theme, “Beauty and Difference”, Lea explores colonial politics through the medium of landscape and architecture. Landscape painting has a well-established place at the RA, with artists such as John Constable, Thomas Gainsborough and J.M.W. Turner coming quickly to mind. William Hodges’s View of Oaitepeha Bay, Tahiti (1776) inscribed Tahiti as a feminised space of sexual availability, while his diploma work The Ghauts at Benares (1787) deployed a classicising aesthetic filter. These sorts of tropes are redeployed to different ends in the contemporary work of Mohini Chandra, such as Imaginary Edens/Photos of my Father (2005-15). Chandra cuts out silhouettes of her father from photographs to reflect the experience of migrations: his “corporeal absence”, she notes, “alludes to the diasporic experience of in-between-ness”. In another example, a different sort of absence concerns the artist Barbara Walker, whose ongoing project Vanishing Point address the lack of Black representation in national archives and, by implication, the collective memory of British society.

Whale Falls (2017) by Ellen Gallagher explores the transportation of enslaved people from Africa to the Americas

Photo: Ernst Moritz; © Ellen Gallagher; courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

The book’s final theme of “Crossing Waters” opens with Thompson’s powerful essay, “The Aquatic Sublime”, addressing the lives of enslaved people lost at sea, something she links directly to the largest of the RA’s galleries, calling it “a space to mourn and reflect on these lives, bringing past and present together to explore the ongoing aftermaths of the Middle Passage”. The Middle Passage refers to the forced transport of enslaved people from Africa to the Americas, one leg of a brutal triangular trade route. Thompson’s mention of the RA galleries returns the reader to a collective space of reflection, where the book began, and, by association, a collective sense of responsibility. This is visualised in Turner’s abstraction in Seascape with Buoy and Whalers (around 1840) and Ellen Gallagher’s Whale Falls (2017), for example. Interestingly, Turner exhibited another painting, Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On) in the RA’s Annual Exhibition in 1840, held concurrently with the first meeting of the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London.

Taking a stand

By way of a conclusion, Lea asks, “Where to from here?”. Olu Ogunnaike’s I’d Rather Stand (2022) is presented as a possible way forward. Ogunnaike’s practice interrogates the social, historical and material properties of wood. I’d Rather Stand takes the form of Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth, a site for “successful artists” as Ogunnaike observes, originally installed in 1841 when the RA occupied the same building as the National Gallery. Ogunnaike’s plinth, made of waste faux hardwood—the luxury veneers for exported furniture now pulverised to appear like cheap, temporary hoarding—brings Britain’s history of “mercantile and naval might”, as Lea notes, “into dialogue with current debates about the role of monuments in the public realm”. Furthermore, the title, in the artist’s own words, declares a preference for the work to “be a stand-in for me”, “as opposed to just being represented by the words of others”. As the artist is a recent graduate of the RA, this is perhaps an instance of the institution dismantling itself from the inside out.

This is just one of the many fascinating, intelligent and instructive examples scrutinised in this book, each of which takes the reader on a particular journey while adding to a strong, overarching narrative of the need for collective reflection on entangled pasts. Ultimately, this book is a provocation and a call to action for other institutions to do likewise.

• Entangled Pasts, 1768—now: Art, Colonialism and Change. Essays by Dorothy Price, Sarah Lea, Esther Chadwick, Cora Gilroy-Ware, with section introductions by Sarah Lea, Rose Thompson and Alayo Akinkugbe. Royal Academy of Arts, 192pp, 125 colour illustrations,

£25 (hb), published 22 January.

• Entangled Pasts, 1768–now, Royal Academy of Arts, London until 28 April