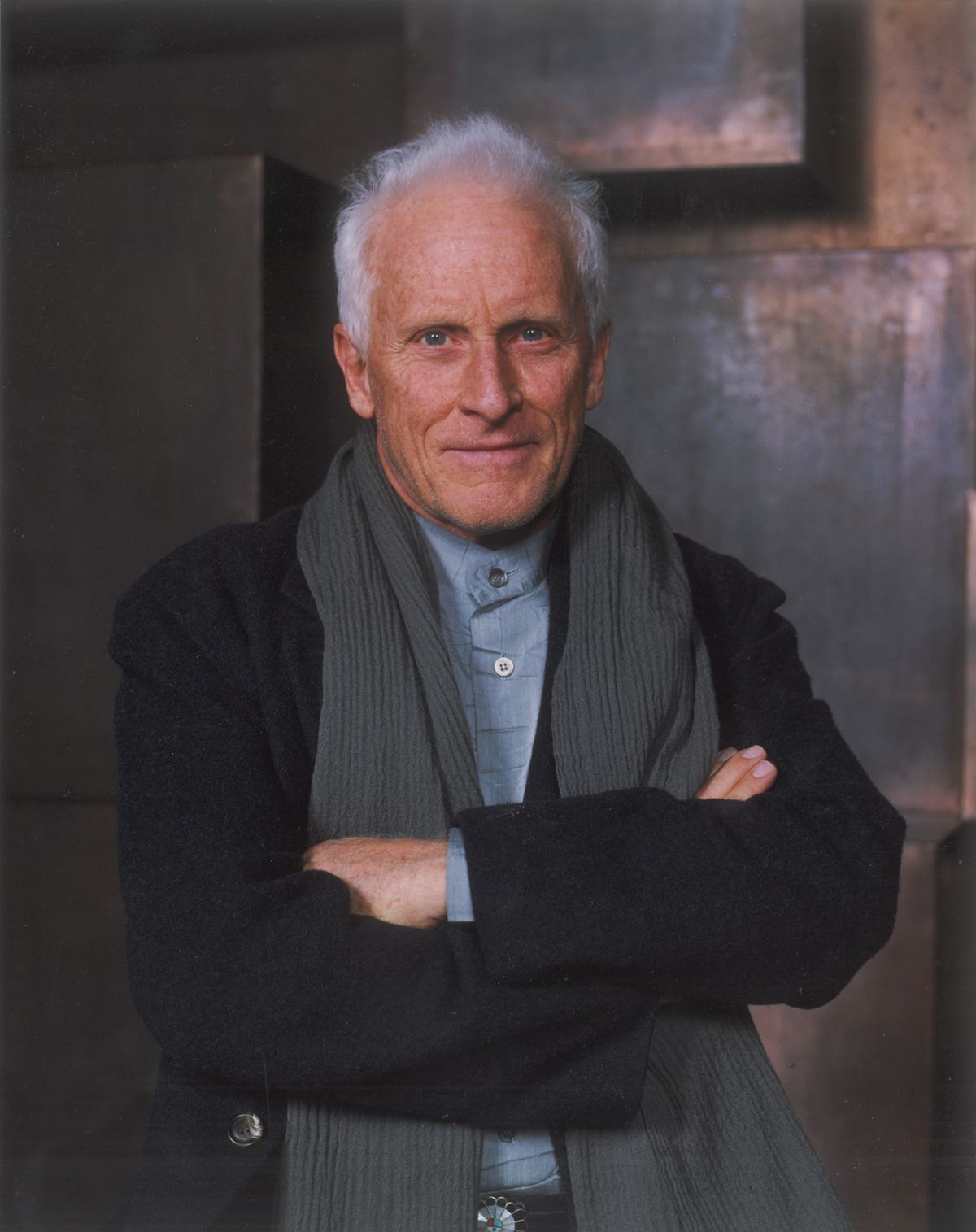

The acclaimed architect Antoine Predock died on 2 March at his home in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He was 87 and had been suffering from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a lung disease.

His architecture is a feast for the senses—not just the visual but also the tactile and the experiential—fusing elements of modernism and post-modernism. Part architectural alchemist and magician, part anthropologist who read deep into each project site, Predock engaged emphatically with the spirit of a place. His buildings express solidity and transparency, an earthy and an esoteric quality, a sense of mystery and a dose of monumentalism all at once. “The best buildings are time travellers,” he once said, a criterion many of his buildings met.

Predock’s early studies in engineering, his training as an artist and with the legendary choreographer Merce Cunningham, and his marriage to a dancer in the 1970s, all influenced his oeuvre. Long dismissed as a “regionalist” by the centres of power in American architecture, the Missouri-born architect set up his practice in Albuquerque, describing New Mexico as a “force that has entered my system” in a 2014 interview, adding: “The lessons I’ve learned here can be implemented anywhere.”

The Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg, designed by Antoine Pedrock, was completed in 2014 Photo by Ken Lund, via Flickr

The self-described “portable regionalist” won the prix de Rome in 1985 and garnered wider attention with his Nelson Fine Arts Centre in Arizona in 1989—his first national design contest winner—of which The New York Times critic Paul Goldberger noted, “he is a theatrical architect who has the discipline to control his theatre”. Before long, he was gracing the pages of Vanity Fair and earning commissions from Disney’s Michael Eisner.

Predock was prolific over the ensuing decades, seemingly driven by a pure passion for architecture. Well into his 80s, he drove an impressive collection of motorcycles and described architecture as “a physical ride”. He is known to have skied and skateboarded on his buildings, encouraging others to enjoy a similarly visceral engagement with his work.

His projects included private homes, residential developments, major civic projects like stadiums, educational facilities, museums and more. An early hallmark, his precedent-setting, adobe-inspired La Luz community in New Mexico, was completed in 1969. His concrete Venice House , completed in 1991, boiled down its Los Angeles locale into essential elements of sea and sky. His Mandell Weiss Forum and La Jolla Playhouse in San Diego, with mirrored walls that disappear into the horizon, was also completed in 1991.

George Pearl Hall at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, home to the School of Architecture and Planning, was designed by Predock and completed in 2008 Photo by PerryPlanet, via Wikimedia Commons

More recently, his distinctive Canadian Museum for Human Rights opened in Winnipeg in 2014. Its “tower of hope” resembles a modernist take on the mosque of Samarra, encased in an icy blue exterior that echoes the nearby prairie and the cold Assiniboine river. The museum, which Predock described as “a unifying and timeless landmark for all nations and cultures of the world” was also his “favourite” and “most important” building, he said, “carved into the earth and dissolving into the sky”.

It was far from Predock’s only museum project. His first, a renovation and expansion of the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe, opened in 1979. His Tang Teaching Museum in Saratoga Springs, New York, inaugurated in 2000, resembles a lightbox installation sculpted into the earth. Two years later his building for the Tacoma Art Museum in Washington state was completed.

Throughout his career, art remained central to Predock’s architectural practice and he continually studied the sketches of his two main architectural influences, Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Kahn. An exhibition of Predock’s sketches, drawings and paintings—spanning from his days as a student of Elaine de Kooning at the University of New Mexico to his architectural collages—will take place at the New Mexico Museum of Art’s Vladem Contemporary space in Santa Fe next year.