The Greek American artist Lucas Samaras, who eluded simple categorisation over his six-decade career, has died, aged 87. He died on 7 March at his home in Manhattan of complications from a fall. His death was confirmed by Pace Gallery, which has represented the artist for over five decades.

Samaras emerged in the downtown New York art scene in the 1950s, becoming best-known for creating self-referential works that spanned a multitude of media from paintings, photographs, installations, drawings, sculptures and more.

Samaras was born in 1936 in Kastoria, Greece, and immigrated to the US in 1948, where his family settled in West New York, New Jersey. He was raised Greek Orthodox, an influence that informed his practice. Samaras did not speak English when he moved to the US and drew and painted in school, where his teachers encouraged him to pursue artmaking. He had a contentious relationship with his father, a furrier who discouraged Samaras from becoming an artist and for whom he worked for a short period of time.

Samaras studied art history at Columbia University under the influential art historian Meyer Schapiro in 1959 but did not graduate, going on to pursue acting at the Stella Adler Studio of Acting. He had previously studied art at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, between 1955 and 1959, enrolling in the art programme with a scholarship he had been awarded through a high school competition.

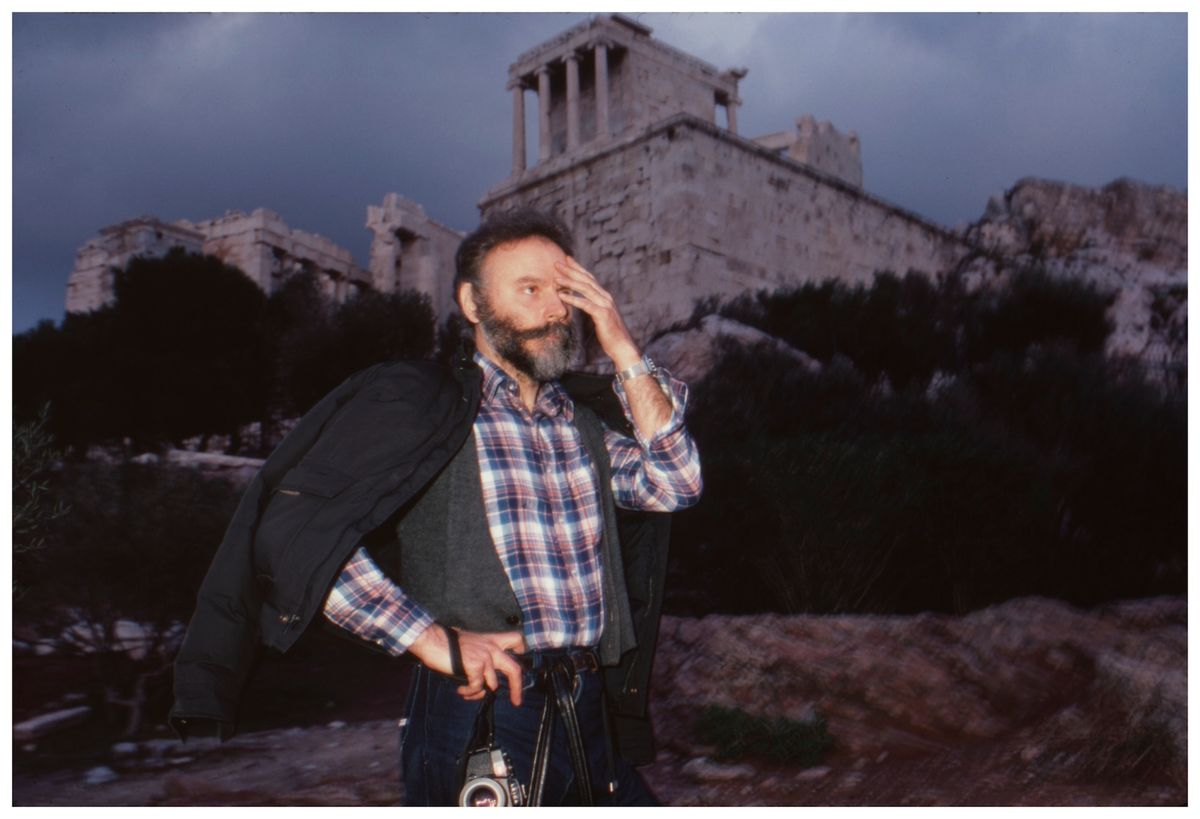

Lucas Samaras in his exhibition Lucas Samaras: Selected Works 1960-1966 at Pace Gallery, 8 October-5 November, 1966 Photography courtesy Pace Gallery

Some of his instructors at Rutgers included the artists George Segal and Allan Kaprow, the latter of whom served as chairman of the department when Samaras enrolled. He participated in several of the Happenings Kaprow organised in the 1950s—conceptual works that combined installation and performance, and which appealed to his training as an actor—like 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959) at the artist-run Reuben Gallery. Samaras also met fellow student Robert Whitman at Rutgers, an artist with whom he would collaborate throughout his career.

One of Samaras’s first notable exhibitions was at the historic Green Gallery in New York in 1964, where he re-created his bedroom and studio after being forced to move out of his childhood home. In a series of auto-interviews he conducted in the 1970s, Samaras explained that he used himself as the departure point of his practice because it was “still unorthodox” to so, and as a means to circumvent “all the extraneous kinds of relationships” involved in finding models, workers or geometric elements as a reference.

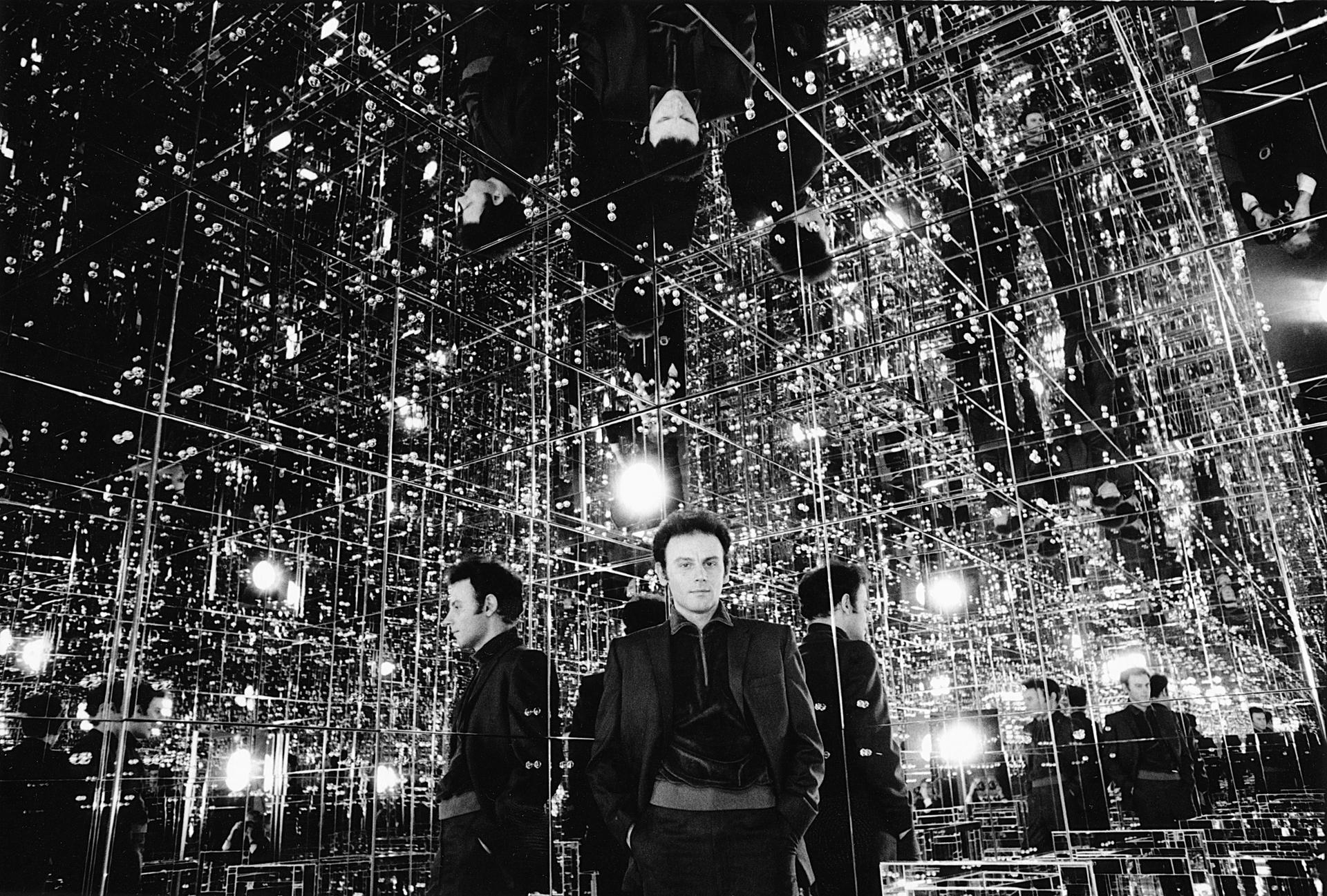

In the beginning of his career, Samaras made several abstract paintings and pastels, some of which were donated to the Morgan Library and Museum in New York. After shifting his focus from performance, he began creating box sculptures and Surrealist-influenced assemblages. Starting in 1966, he began creating immersive works that visitors could enter, covering the structure with glass and reflective material in a similar style to Yayoi Kusama, who created her first Infinity Room shortly before in 1965. He began working with a Polaroid camera in the late 1960s, going on to create hybrid photograph-paintings and other forms of manipulated photographs.

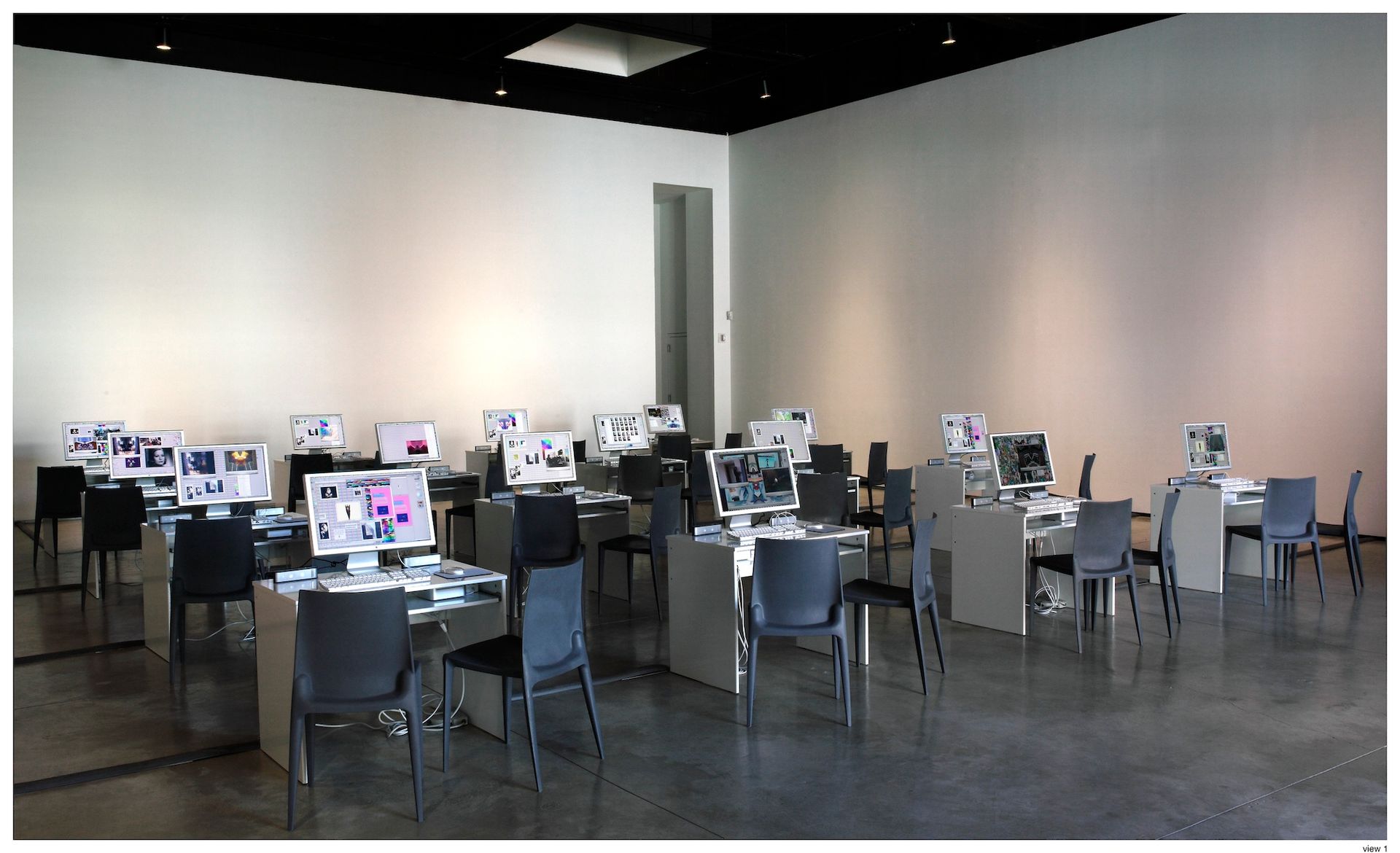

Lucas Samaras: PhotoFlicks (iMovies) and PhotoFictions (A to Z) at PaceWildenstein, 8 April-7 May 2005 Photography courtesy Pace Gallery

Samaras once said that, although he never felt compelled to stick to a particular format or direction, there are subtle correlations in his work that are rooted in perspective, emotion and selfhood. “There are some people who spend years and years working on a particular format, and I don’t do that, I can’t do that,” Samaras said in a 1966 interview with Artforum. “I supposed it has to do with my reworking of whatever seems to be reality.”

He added, “I see the world differently at different times. And sometimes it’s pleasing and sometimes it’s not pleasing, consequently the work changes. What I do changes, the quality of what I do changes, so that I’m not interested only in the formal problem. I’m interested in the psychological, biographical or social.”

Pace organised the exhibition Albums at its flagship New York City location in 2022, showcasing the artist’s years-long project of constructing an illustrated archive, and published Flowers last year, a volume featuring a series of psychedelic digital distortions.

Installation view of Lucas Samaras’s PARAXENA at the Greek Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale at the 53rd International Art Exhibition in Venice. 7 June-22 November 2009 © Lucas Samaras

Before his death, Samaras was preparing for a major exhibition opening in September at Dia Beacon in upstate New York, the centrepiece of which will be a collection of minimal sculptures titled Cubes and Trapezoids (1993-94). Dia acquired the series of 24 totemic wooden sculptures in 2003 and will exhibit them together for the first time since their debut at Pace in New York in 1994. The exhibition will also feature an immersive mirrored room, titled Doorway (1966-2007).

The artist’s work is included in major international museum collections such as the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Tate in London and the Iwaki City Art Museum in Japan, among others. He represented Greece at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009. That year, in an interview with Pace Gallery founder Arne Glimcher for Interview, Samaras described his process for creating new works as one of discovering connections to the past.

“When I set out to do a piece and I find I’m doing something different from what I’ve done before, invariably I’ll make two, three, four, whatever and then I’ll find, all of a sudden—it’s like a bell ringing—that the piece I’ve just made has connections to the past,” he said. “I’ll remember a mood that was in a painting by so-and-so in the 1400s or the 1780s, you know what I mean? And when I see that, to me, it’s an indication of pay dirt. It means I’m connecting to something real, something that happened, something that has automatic substance. And these hints of the past just blow my mind.”