The German artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) was shaped by the aesthetic innovations of pre-First World War Europe, but she infused her stubbornly figurative art with political convictions and a moral ferocity that connect her with the era’s activists rather than its experimental artists. Following her death aged 77 in 1945, a matter of days before the collapse of Nazi Germany, her standing as a moralist made her useful for several generations of post-Second World War German politicians and image-makers, yet arguably left her underappreciated as an artist. Now, two large surveys opening this month on either side of the Atlantic are asking everyone to look anew.

At the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, Käthe Kollwitz will use around 110 works, stretching from the early 1890s to the early 1940s, to present the whole of her career as draughtswoman, printmaker and sculptor. Starr Figura, the curator in MoMA’s department of drawings and prints, says it is the first time in more than 30 years that US museumgoers will have a chance to see Kollwitz works gathered from major collections across the US and Europe. Meanwhile back in Germany at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, Kollwitz will revisit the artist’s working life and her contested legacy in her native country.

Born Käthe Schmidt in east Prussia in 1867, Kollwitz moved through artistic institutions in fin-de-siècle Munich and Berlin before settling down in the new German capital in the early 1890s with her husband, doctor Karl Kollwitz, who set up his practice in what was then the working-class district of Prenzlauer Berg. She quickly found inspiration in her growing sense of injustice at the conditions of the lives around her. However—as both shows will demonstrate—her first and greatest subject was herself.

Kollwitz's Self-Portrait (1891/92) © 2024 ARS, New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

MoMA will begin its exhibition with a number of early self-portraits on paper, including a striking work on brown paper, on loan from the Art Institute of Chicago. Combining black, white and grey gouache, and marked by a penetrating stare, the work is “just an incredible piece,” says Figura, who admires the way the brown surface functions as a fourth colour in the portrait.

Though she briefly fell under the sway of French artists like Edgar Degas and Pierre Bonnard, whose work she encountered in Paris in the early 1900s, Kollwitz gave up painting to concentrate on near monochromatic drawing and printmaking. “Colour introduced a decorative effect,” Figura says, which the artist came to see as “incompatible with her socially critical messages”.

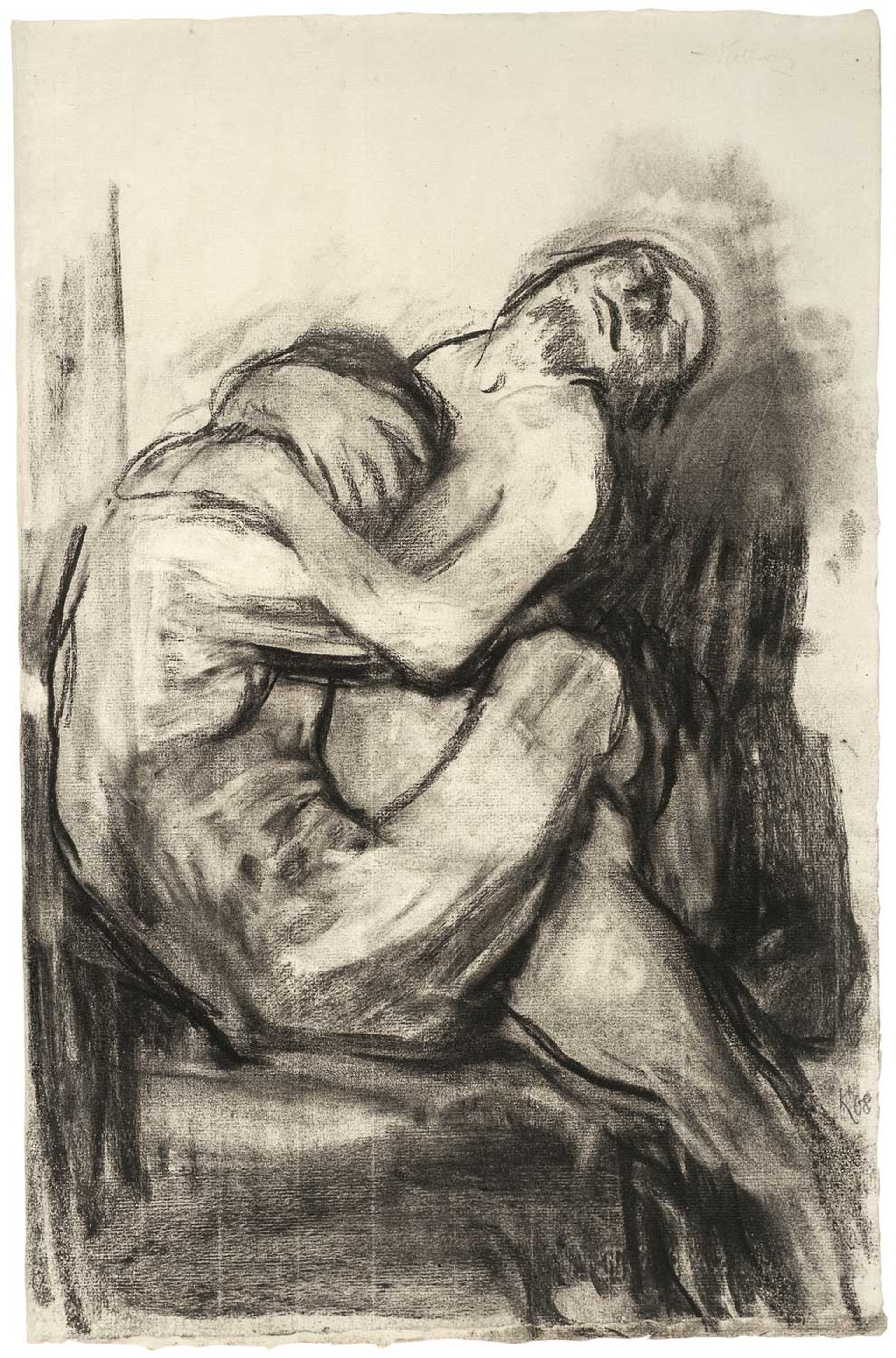

An interest in colour did co-mingle with her social awakening, however, and both shows may surprise Kollwitz admirers, with works such as 1903’s Weiblicher Rückenakt auf grünem Tuch (female nude, from behind, on green cloth). The crayon-and-brush finished lithograph, printed in two colours, feels a lifetime away from the suffering mothers that mark so much of her oeuvre, as do erotic works, like Liebesszene I (love scene I), a drawing in black crayon from around 1909-10, on loan to MoMA from Cologne’s Käthe Kollwitz Museum. Figura says the drawing belongs to a category of works, never shown in her lifetime, produced in response to a passionate affair.

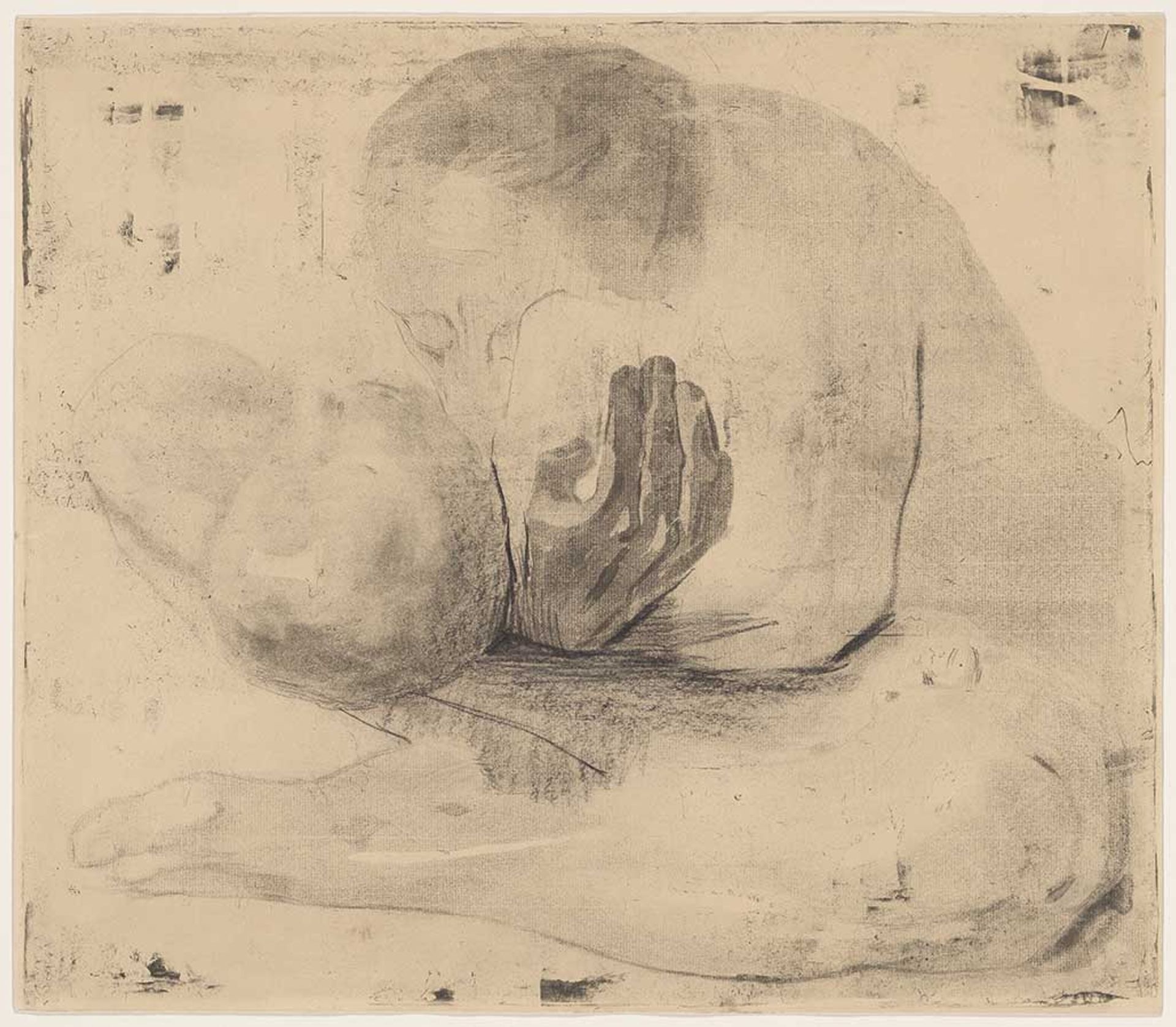

Kollwitz’s etching Frau mit totem Kind (1903) with charcoal shadow Photo: Martin Parsekian; MOMA, New York

MoMA gets behind Kollwitz’s working methods by presenting a wide range of proofs used to create some of her best known images, such as 1903’s etching, Frau mit totem Kind (woman with dead child), which mysteriously conflates a concern for infant mortality with pacifism. The show will include the very first state, a ghostly work in its own right, with charcoal shadow added by Kollwitz’s hand.

The grieving-mother motif turned out to be a premonition. Kollwitz used her own son, Peter, as a model for Frau mit totem Kind, and later he himself would fall in the First World War. Kollwitz’s primary vocation as a graphic artist was later modulated by an interest in sculpture, and the Frankfurt show will display her 1937 small bronze Pietà (Mutter mit totem Sohn), on loan from the Berlin State Museums, in which the mother figure holds the collapsed adult son between her legs, in a vision that mimics the act of birth.

Kollwitz's Love Scene I (Liebesszene I) (around 1909-10) Käthe Kollwitz Museum Cologne

An enlarged version was at the heart of a major controversy in the early years of German unification, when it was installed, under the personal instruction of the then chancellor Helmut Kohl, as an all-encompassing memorial in honour of Germany’s victims of war and tyranny. The exhibition will revisit the debate, and consider the artist’s post-war fate on either side of Germany’s Cold War border, when the West stressed her moral gravity—at the expense, perhaps, of her art—and the East regarded her as a forerunner of Socialist Realism.

The timing of the two shows may be a coincidence, but Figura believes that the world is only now ready to fully appreciate Kollwitz’s achievements. “She was promoting a vision of compassion as a way to respond to injustice and horror,” and she was minimised and even belittled for that, Figura says, but compassion in art “is something we talk about now”.

• Kollwitz, Städel Museum, Frankfurt, 20 March-9 June

• Käthe Kollwitz, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 31 March-20 July