The Jamaican-born, New York-based artist Nari Ward is known for his powerful sculptural installations created using humble discarded materials frequently found and collected throughout his neighbourhood of Harlem. Whether Ward is combining more than 300 baby buggies with flattened fire hoses (the 1993 installation Amazing Grace) or rolling a giant ball of tumbleweed made from the toecaps and laces of shoes onto slices of vinyl advertising hoardings (the 2015 sculpture Tumblehood), his assembled works confront complex social and political realities surrounding race, migration, democracy and community.

The late curator Okwui Enwezor, who included Ward in his 2002 Documenta 11 exhibition, said that the artist had “completely transformed the scale and the ambition of installation art”. From an early showing in the Aperto section of the 1993 Venice Biennale, Ward has gone on to exhibit worldwide, from Siena to Sharjah, with significant solo shows at the New Museum in New York, the Pérez Art Museum Miami and the Fondazione Trussardi in Milan, among others. A new survey at Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan next month will focus on Ward’s time-based media work as well as performative sculptures and installations.

The Art Newspaper: Your exhibition at HangarBicocca will span three decades and take “performativity” as its central theme. At its heart are three large-scale installations that were originally conceived as sets for the choreographer-writer Ralph Lemon’s Geography Trilogy between 1997 and 2000, and which are being shown in a museum context for the first time. Can you talk about this crossover with performance and why it is so important?

Nari Ward: Ralph was always interested in what I was doing in the studio, so it wasn’t a conventional set design relationship but a bridging of the studio in dialogue with his ideas. With the pallet wall [Geography Pallets, (2000/24)], for instance, Ralph was talking about temples and the conveyance of ideas and devotion and I was at that time thinking about the port as a non-space of exchange and of marked merchandise moving through. He was willing to engage with those ideas and then figure out how we can bring the reverential and the devotional back into it. It actually happened in a particularly great way because when we got it up on the wall, the sugar and plexiglass combination basically created a stained-glass window. Throughout there were moments like that, where Ralph knew what he wanted, but he needed to have it translated through me and my vision.

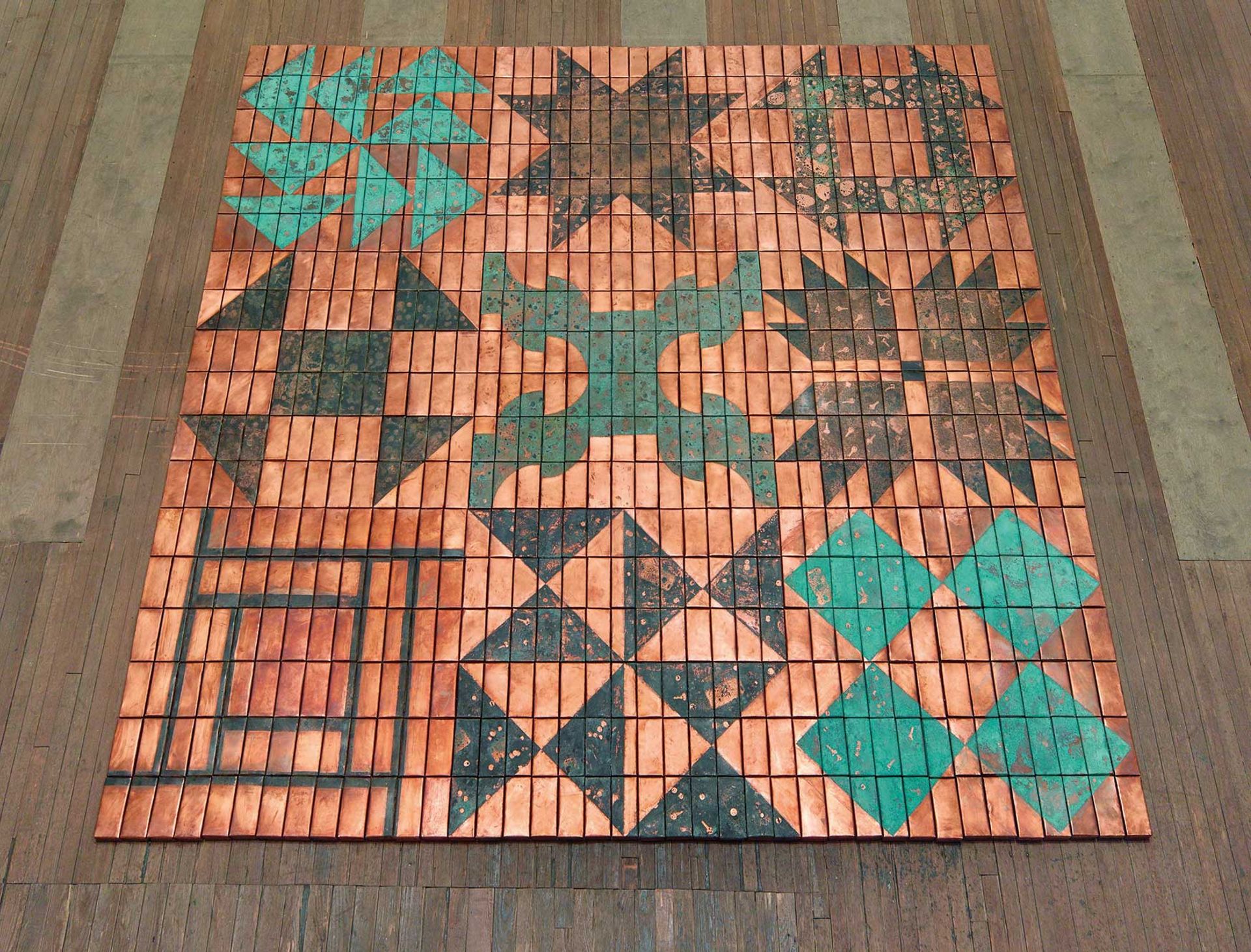

Freedom, this way: the symbols on the copper-sheathed bricks in Ground (In Progress) (2015) echo the coded directional signs on quilts used on the Underground Railroad to indicate the next stop on the slaves’ escape route Photo: Max Yawney

Beyond your work with Ralph, you have also made your own performances and worked with others, most recently using dancers to activate your copper-brick floor pieces—so this live element is still central to your work.

From the very beginning my desire to become an artist was about trying to engage with two materials: the material of space and the material of time. In terms of material space, the strategy was that I would find this functional or discarded object and then get enough of it so it could take on space and create another kind of overall presence for the viewer’s body to occupy. Then for the idea of time, it was about history. I would find things that in the past had a kind of marker of time inherent in them. The attraction was that they had gone through a process that triggered some kind of unforeseen history in terms of their logic of time. So I was always thinking about how to bring this two-way conversation into a space.

There are so many strands to your use of found objects. The way in which they are gathered, assembled and reconfigured also seems to chime with many moments in art history, whether the assisted readymades of Marcel Duchamp, the architectural assemblages of Noah Purifoy or Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines, to name but a few. Then there is also the historical and political aspect of working with objects ranging from baseball bats to discarded bottles and baby strollers. But throughout, it always seems essential that these objects are not only salvaged but also laboriously worked on, often incorporating historically loaded substances such as sugar, oil and cotton.

I love the legacy of Purifoy, Rauschenberg and John Outterbridge and I reflect on their engagement with resistance. For John it was the [Watts] riots in LA, and how to register that visually and tell that story in a meaningful way. I think we’re all storytellers—even Duchamp is a storyteller. And that was what guided me and led me to become a found object artist. I’m very much an artist produced by that boilerplate of Harlem in the 90s and those different kinds of pressures that were going on. There was HIV and Aids, we had the white flight from the urban centres, a lot of poverty and the arrival of crack cocaine, which literally wiped out these neighbourhoods. Then governments came in and started giving out different grants to corporations to rebuild the neighbourhoods. So that was all happening and then I would go to my studio. And because I was going to a graduate programme for drawing, I’d try to make marks on paper. And I got frustrated with that and felt like I needed to try to tell the stories of what was really going on in my neighbourhood at the time.

And to use objects to tell these stories?

The dialogue with these objects was important. It wasn’t that these objects were in the garbage: I never picked them up on the sidewalk, they were in an empty lot. For me it was that desolation around this thing that was part of somebody’s life and part of somebody’s routine and rhythm that resonated and then inspired me to figure out how to tell a story that wasn’t just my story. It was always about taking the personal and figuring out how to materially seduce the viewer. I’d also use sugar and stuff that people had their own experiences with, so I could try and waylay those experiences into the conversation.

You had a Baptist upbringing, and in many ways religion and a sense of spirituality reverberates through your work. Even if the religious references are not overt, there is a votive, ritualistic feel to your often laborious and repetitive wrappings, burning and assembling of materials.

It’s back to that conversation with time. I remember my mentor, the painter William T. Williams, got me to look at these African devotional figures. Not just their form but their surfaces, because a lot of them would have had libations poured on top. This created a kind of mystery that took them out of the present moment and into a ceremonialised dialogue with time that had its own rhythm. So when, for example, I was coating these things that I was finding on the street with sugar or with bitumen I was thinking about libation, and that patina and how the mysterious power of unknowable ceremony can be engaged for the viewer, to trigger the imagination in the viewer, to have this thing become more than what they normally would perceive it to be, and to create a kind of hyper materiality.

Yet alongside images of deprivation and disintegration you always seem to include flashes of humour and a sense of redemption.

Trying to put this into practice is a constant struggle, but I always want to think about hope.In finding discarded materials and creating an environment for them to exist and to have meaning echoed through their combinations, I feel like a sense of hopefulness is always present. There has to be potentiality for hope to exist and by working with found objects that are discards I really feel like that potential is a constant material for contemplation. Like time and space, hope is also a material for me.

Ward's Savior (1996) Photo: E.G. Schempf

Biography

Born: 1963 St Andrew, Jamaica

Education: 1989 BA from Hunter College; 1992 MFA from Brooklyn College, City University of New York

Lives and works: Harlem, New York

Key shows: 1993 Venice Biennale; 1995 Whitney Biennial, New York; 2002 Documenta 11, Kassel; 2011 Mass Moca North Adams; 2015 Pérez Art Museum Miami; 2019 New Museum, New York; 2022 Fondazione Nicola Trussardi, Milan

Represented by: Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul and London; and Galleria Continua

• Nari Ward, Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 28 March-28 July