Art Dubai’s Modern section looks at how the former Soviet Union forged cultural links with regions such as the Middle East, Africa and South Asia. Many artists took part in cultural exchange programmes with the Soviet Union during the Cold War era, says Christianna Bonin, the curator of Art Dubai Modern and assistant professor of art history at the American University of Sharjah.

“Despite coming from diverse cultural backgrounds, these artists reveal shared creative approaches, setbacks and aspirations as a result of their common experiences in the Soviet context,” Bonin says. “Emerging from these circumstances, the works on view foreground the many ways artists honed a personal vision by navigating unfamiliar histories, cultures and methods of art making.”

We asked Bonin to pick out some of her highlights from Art Dubai Modern.

Hakim Al-Akel, Dialogue in the Market (1991), Hafez Gallery

Though a portion of Hakim Al-Akel’s work addresses the ongoing civil war in his hometown of Taiz in Yemen, the artist now shies away from representing violence. He remains faithful to his whimsical “other world” in Yemen, rejecting the prevalence of war and instead framing quiet intimacies from his past. His figures lack shadows, which gives this scene an unreal quality and allows viewers to connect their own emotions and memories to the work.

Courtesy Saskia Fernando Gallery

Chandraguptha Thenuwara, Mother and Child (1998), Saskia Fernando Gallery

This painting draws on the mother-and-child archetype of Eastern Orthodox icons, but in place of the traditional gold background, Chandraguptha Thenuwara adds camouflage—a prevalent motif in his practice that alludes to the common use of camouflaged barrels at military checkpoints during the civil war in Sri Lanka. The child’s hidden face, pressed against its mother’s chest, reflects the protective peace of a mother-child relationship, nevertheless unsettled by a war-time pattern with daggers in the background.

Courtesy the artist and Mark Hachem Gallery

Fatima El Hajj, Yellow (1995), Mark Hachem Gallery

Like speckles of sunlight, Fatima El Hajj’s dynamic brushstrokes and vibrant palette enliven her subject matter; here a floral still life.

Courtesy Afriart Gallery

Samuel Kakaire, Grain Pounding at the Mortar (1995), Afriart Gallery

Samuel Kakaire specialises in tempera, oil and watercolour, excelling in both miniature and large-scale mural paintings—European art forms unfamiliar in Uganda, where the principal creative medium has always been music, particularly during the country’s pre-colonial period. Kakaire’s work combines scenes of everyday life in Uganda with formal techniques learned during his studies in the former Soviet Union in the 1980s, such as an emphasis on gesture and central figures set against an ethereal ground.

Courtesy Voloshyn Gallery

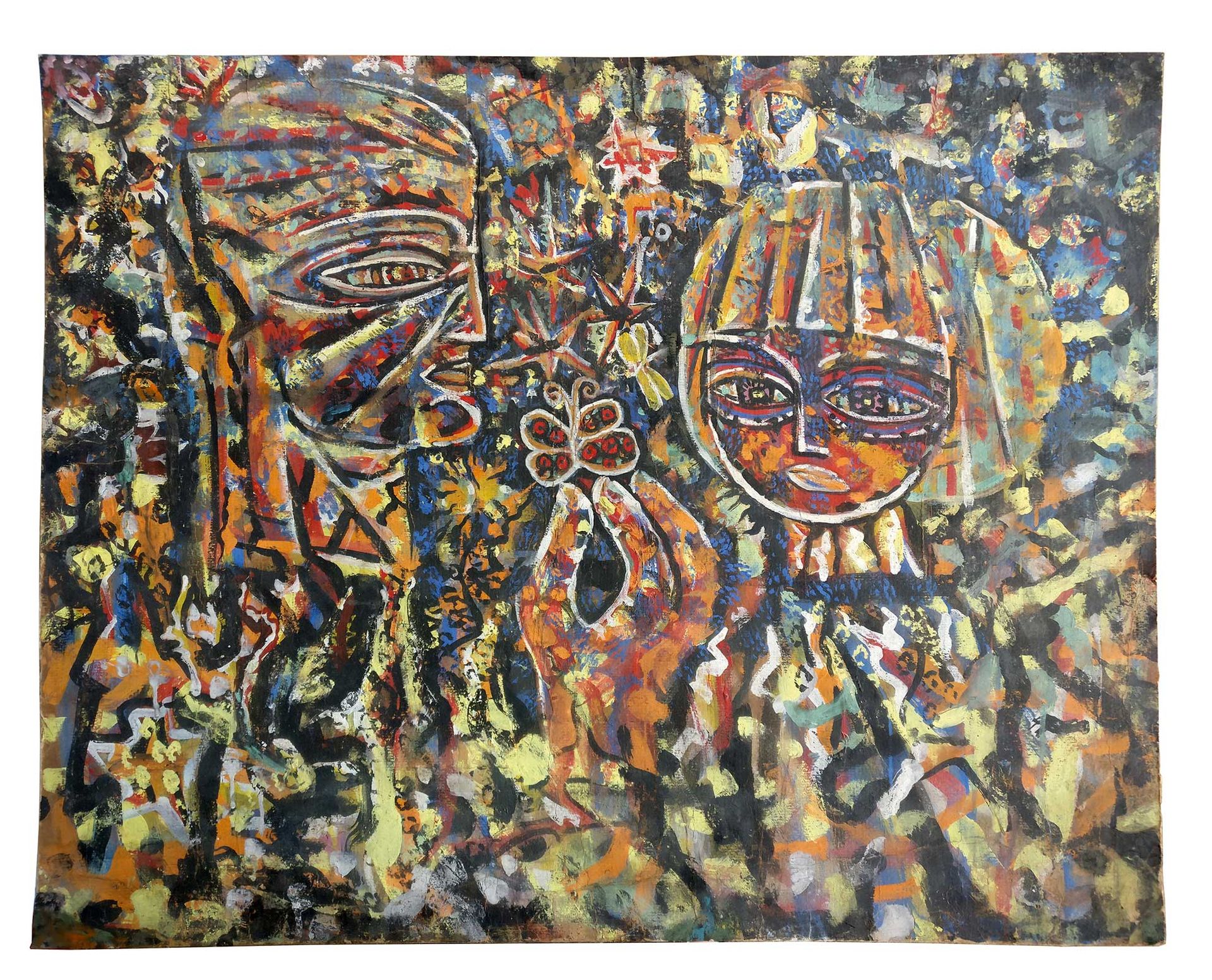

Fedir Tetianych, Wonderworld (1970s), Voloshyn Gallery

Ukrainian artist Fedir Tetianych never felt comfortable working in conventional art studios with standard materials, often electing instead to create his own universe through found materials, street performance and the written word. Wonderworld conveys one of his most important messages—a sense of boundlessness and continuity between humans and nature—with a bright palette washing over the male and female figures.

Courtesy Gazelli Art House

Farhad Khalilov, from the series Meeting (1983-2000), Gazelli Art House

Without any obvious story or event, Farhad Khalilov’s street scenes and landscapes ask viewers to focus instead on the cool colours of the seaside evening. As in this painting, Khalilov often works towards the minimum gesture: how many visual details do we need to recognise an ocean wave, for example? Here, just wispy brushstrokes suffice.

Courtesy Leila Heller Gallery

Marcos Grigorian, Untitled (1979), Leila Heller Gallery

Mainly using earth and straw as opposed to oil paint and canvas or other traditional European art media, Marcos Grigorian made minimalist works from humble materials. His experiments with soil and found objects refer to the desert and indigenous building materials in Iran, where he spent his formative years as an artist. The simple format of the square became his signature composition, a shape that allowed the artist—who moved between Armenia, Russia, the United States and Iran—to produce serenely balanced and grounded objects.

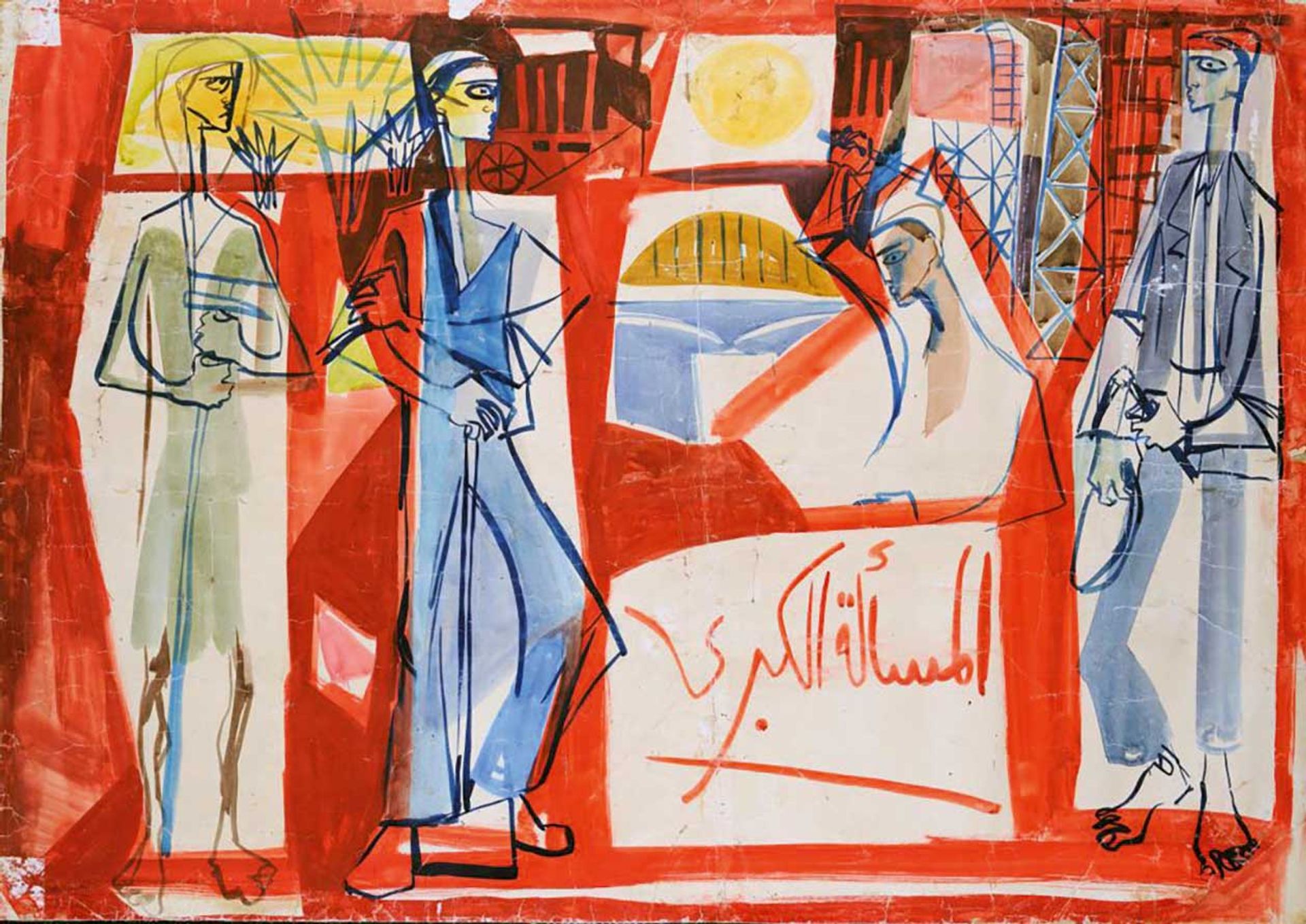

© Mahmoud Sabri. Courtesy Meem Gallery

Mahmoud Sabri, Untitled (1960s), Meem Gallery

Mahmoud Sabri’s strong contour lines and primary blocks of colour give structure to this scene of four workers. Behind them, a rail car and scaffolding suggest a construction site, while one figure lifts a hammer, intent on pounding it against the Arabic word “Al-Mas’ala Al-Kubra” (المسألة الكبرى), or the “main question”. Well-versed in Marxist art and culture, and engaged in the political transformation of his birth country of Iraq, Sabri’s works interlace abstract aesthetics with realistic and symbolic references—the industrialisation of Iraq in the mid-20th century, as well as a worker in local dress holding a shovel, and a suit-clad man holding a sickle, setting up a comparison between “traditional” and “modern” labour.