For the 1974 work Untitled (Body Print), Suite of 5, Ana Mendieta shrouded herself in a sheet, an impression of her body in red overlaid on the draped material. In Blood: Medieval/Modern, the colour photograph is contrasted with medieval depictions of Saint Veronica holding what is known as the Sudarium, a miraculous image of Christ revealed from the blood wiped from his face on his way to the cross.

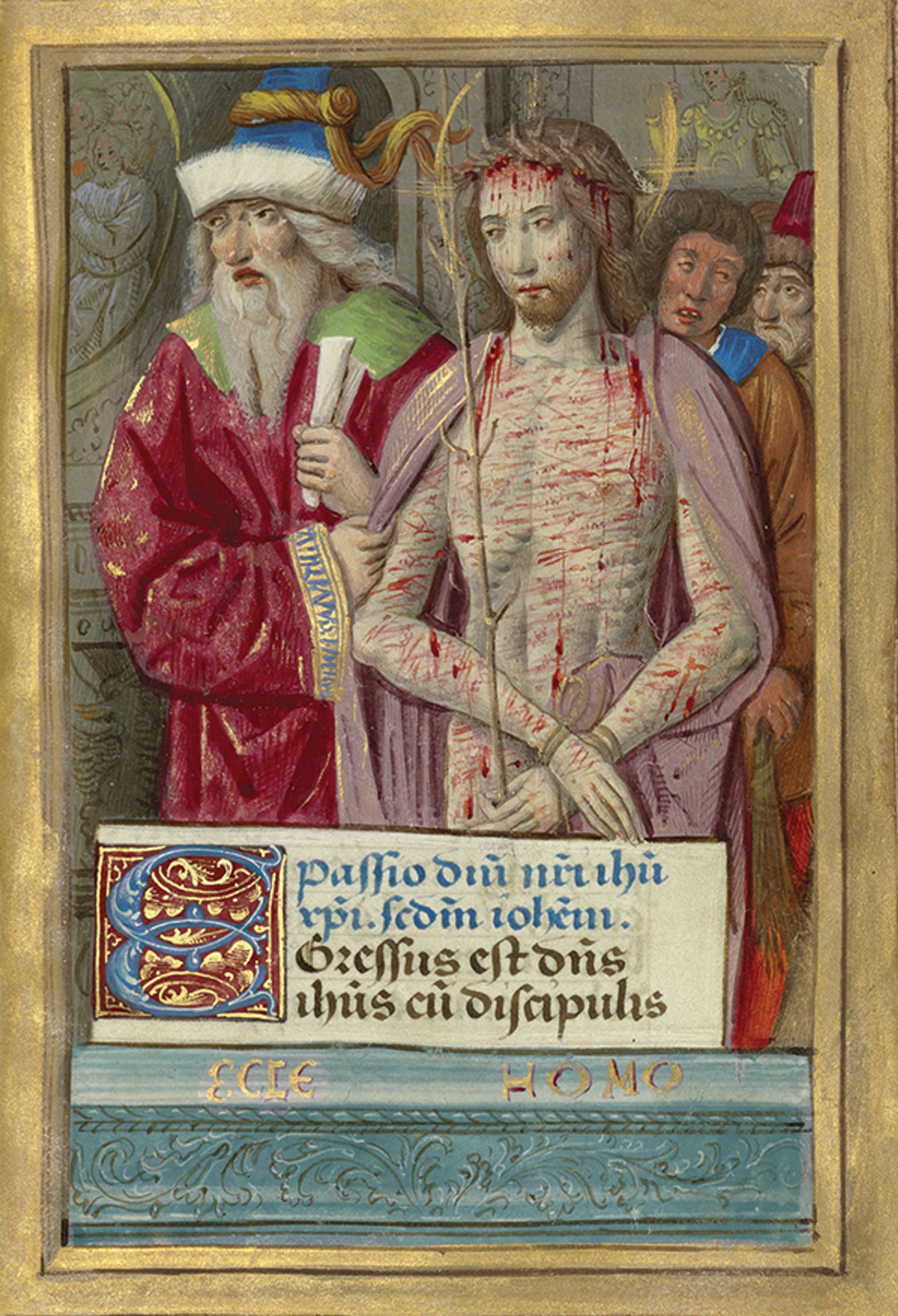

Ecce Homo from Poncher Hours (around 1500) by Jean Pichore Getty Museum

“Seeing this as a Medievalist, I thought of the Veil of Veronica and the idea of a holy bodily substance,” says Larisa Grollemond, the assistant curator of manuscripts at the J. Paul Getty Museum. “The visual correspondence was so strong—the inclusion of the red pigment that Mendieta uses and the lifting of the veil—but she’s doing something totally different as a female artist than medieval manuscript illuminators. Pairing them opens up a new dialogue.”

Blood: Medieval/Modern is the first exhibition to combine Medieval manuscripts with contemporary art in the Getty’s manuscripts gallery. Grollemond says she was initially interested in organising a show examining bloodlines and genealogy, but the online response to a social media video she created about menstruation in the Middle Ages encouraged a broader look at depictions of blood, from prayer books that isolated Christ’s bleeding wounds for meditation to the scarce medieval representations of feminine blood.

From practical to devotional

“Blood exists on so many different levels, both in the Medieval and contemporary imagination,” she says. “There’s thinking about blood on a very practical level, like treating ailments of the blood and thinking about the circulatory system. But then there’s also the devotional aspect, which is thinking about the blood of Christ and this focus on the wounds of Christ as loci for Christian devotion, especially at the end of the Middle Ages. There’s a way that blood really transcends all these different kinds of conversations from a very earthly, physical level all the way up to the spiritual and into the divine.”

Satan Shoes (2021) by MSCHF and Lil Nas X: a drop of blood in red ink is encased in the heels Image: © MSCHF 2021; courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Power, taboos, humanity

Joining works like a striking 1480-90 illustration of the side wound of Christ sliced in geometric angles on the page are modern and contemporary pieces by artists such as Nan Goldin, Ishiuchi Miyako, Catherine Opie and Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle. Several of the included artists, like Andres Serrano, have regularly used blood as a medium for the same power, taboos and humanity that made it so meaningful to medieval artists.

My work intersects with the exhibition’s focus on blood as a substance that can be sacred in certain contexts and repulsive in othersJordan Eagles, artist

Queer Blood America (2021) by Jordan Eagles, who has created art with blood since the late 1990s, particularly to confront longstanding restrictions on donations from gay men, holds a vial of a gay man’s blood within an image of Captain America fighting the supervillain Baron Blood. The comic book was published at the beginning of the Aids crisis, and its framing with blue surgical gloves evokes the borders of Medieval manuscripts that elevated their religious subjects to the divine.

“In addition to the connection in format between Medieval illustrated manuscripts and the modern comic book, my work intersects directly with the exhibition’s focus on blood as a substance that can be sacred in certain contexts and repulsive in others,” Eagles says. “In this work, and all my works, I explore the boundaries of blood being precious and spiritual, yet also stigmatised.” At the coinciding “There Will Be Blood” symposium at the Getty Center on 1-2 March, Eagles will be presenting a site-specific installation layering comic-book narratives about blood, with blood donations from individuals on pre-exposure prophylaxis or who are HIV positive and undetectable.

Among the most recent works are the Satan Shoes (2021) by MSCHF with Lil Nas X, which also employ taboo aspects of blood in their design. As well as a shoebox featuring Medieval art, a drop of blood with red ink was encased in the heel air bubbles of the shoes.

“As a Medievalist, they immediately brought to mind the practice of blood reliquaries and the idea of making something special or quasi-divine by including a piece of a saint’s body or blood in the container,” Grollemond says.

Alongside the visceral scenes of martyred saints, meticulous charts of royal lineage and diagrams for bloodletting, these contemporary works demonstrate how the significance of blood may have changed over time, gaining different anxieties or cultural meanings. But visually portraying it will always be provocative, revealing the hidden substance that flows beneath our skin.

• Blood: Medieval/Modern, Getty Center, until 19 May