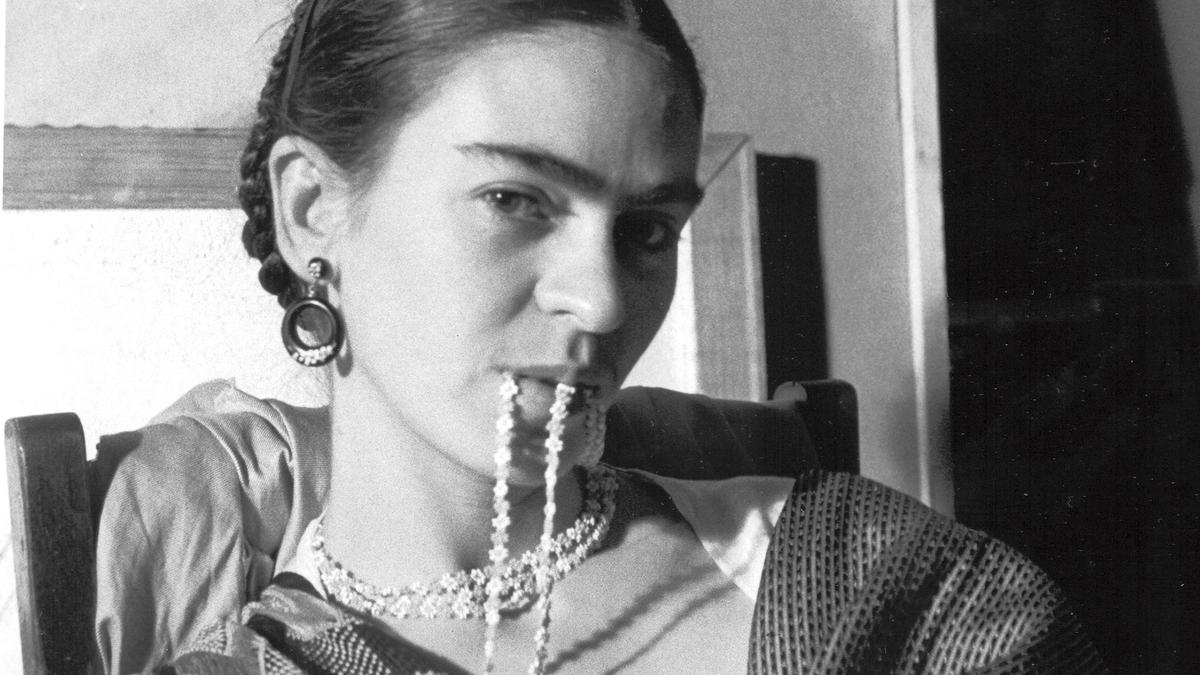

In the documentary Frida (2024), which had its debut at the Sundance Film Festival in January, the director Carla Gutiérrez exhumes Frida Kahlo’s voice, relying mostly on the artist’s words from her diaries and notebooks to portray the woman behind the images that she made. The “Frida effect” has been with us for decades, with exhibitions all over the world, merchandise of every sort, auction prices in the stratosphere and polemics for her lasting role as a prophet of self-portraiture, feminism, Surrealism and sex.

Gutiérrez brings skill as an editor—as evidenced in previous efforts such as the Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Julia Child documentaries RBG (2018) and Julia (2021)—to her directorial debut, weaving in photographs from throughout Kahlo’s life, and animations of drawings and paintings, along with her most famous images. Kahlo’s words here say more about her life than her art, and the film aims at a huge public. The documentary’s executive producers include Brian Grazer and Ron Howard, who collaborated on Splash (1983), Apollo 13 (1995), The Da Vinci Code (2006) and many other mainstream movies.

Gutiérrez has said she looked into the latest academic writings on Kahlo, with the biographer Hayden Herrera credited as a consultant. Herrera’s 1983 book, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo, was also the basis of Frida, the 2002 narrative feature directed by Julie Taymor, with Salma Hayek in the title role.

Performance and pain

Gutiérrez’s film is more distillation than deep dive, more descriptive than groundbreaking. It presents Kahlo’s youth as a period of performance and pain. The daughter of a religious mestizo mother and an atheist photographer father, young Kahlo went to a school where the other pupils were mostly boys, and she often dressed as one in three-piece suits.

Her life was shattered in 1925, when a bus in which she was riding collided with a streetcar, sending a shaft of metal into her body, almost killing her. She lived in pain for the rest of her life. Her injuries, a persistent subject of her work, get the added treatment of animation. Gutiérrez is not the first film-maker to add movement to works of art. One wonders whether Kahlo’s work needs that kind of enhancement, and whether we get closer to the real Kahlo when monkeys dance around her playing hide-and-seek.

Kahlo’s leftist politics owe much to the Mexican Revolution of 1910-20 led by Emiliano Zapata, which turned her into a communist, albeit an unorthodox one. We see her in a drawing, nude and dreaming of Diego Rivera, another communist. During this period, she adopted the Indigenous Tehuana dress that became an integral part of her iconography and figured in her paintings, setting her apart when “Mrs Diego Rivera” travelled to New York in 1932 with her husband for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. There, she was viewed with curious condescension as “birdlike” and was said to “gleefully dabble” in painting.

Privately, Kahlo noted that “Diego is the big shit here”, but “high-society people lead the most stupid lives… they all spout nonsense and brag about their millions”.

‘Rich jerks’

The film includes a section on the couple’s trip to Detroit for a mural commission—“unfortunately, Diego has to work for these rich jerks”. Kahlo found herself pregnant and, deciding against abortion, which would have been illegal in the US, had a miscarriage in July 1932 in the Henry Ford Hospital. She portrayed herself bleeding in bed at the time, with an ashen-skinned baby sitting alongside her.

Back in New York, after receiving a commission to paint murals for Rockefeller Center, Rivera was fired for insisting on depicting Vladimir Lenin in one of them. In this passage, Kahlo calls her hosts “stuck-up gringos”, “motherfuckers” and “sons of bitches”.

Upon returning to Mexico, Kahlo was unabashedly bisexual and sex-positive, declaring that “it’s good to have sex even if it’s not for love”. In 1937, she painted Leon Trotsky, who bored her as a lover. The film ignores his assassination, for which she was arrested and later released. (It also ignores her ardour for Stalin.) Other lovers allegedly included Paulette Goddard, once the wife of Charlie Chaplin. After Rivera seduced Kahlo’s sister Cristina, the couple divorced in 1939, then remarried a year later, agreeing on a bond without sex.

André Breton, who considered Kahlo a Surrealist, gave her a show in Paris. But, angry that Breton put her work alongside Mexican knick-knacks, she said: “I hate Surrealism. It’s a decadent manifestation of bourgeois art.”

Later, she predicted: “I believe that after my death I’m going to be the biggest piece of shit in the world.”

Like so much in popular cinema, Frida is character-driven and full of close-ups. She could paint, she could talk and she could curse like a sailor. We will now find out if anyone did not already know that.

• Frida will be available to stream worldwide on Amazon Prime Video from 15 March