“We do this not to destroy this important part of art history, but for it to be saved—the same as we demand that Julian Assange be saved,” declares Andrei Molodkin. The Russian artist, best known for pumping blood and oil into his often politically confrontational sculptures, is explaining the motivations behind his latest work.

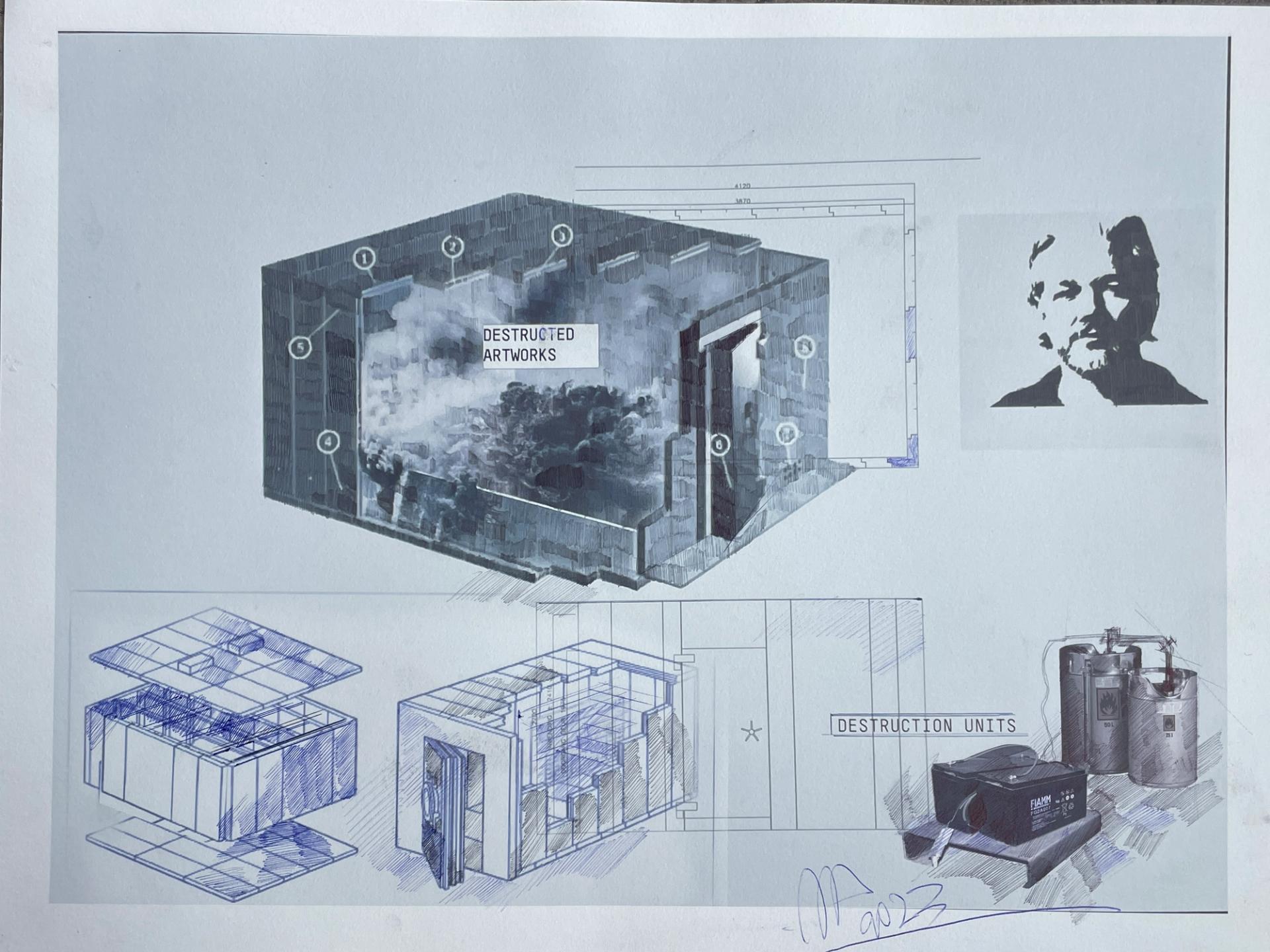

Dead Man’s Switch comprises a specially constructed 32-tonne safe room that has been filled with crates containing a valuable cache of art. Locked in with 16 pieces by the likes of Jake Chapman, Sarah Lucas, Pablo Picasso and Rembrandt—donated by collectors persuaded to the cause, or by the artists themselves—is one of two countdown timers set to a 24-hour loop. Alongside them is a mechanism capable of destroying everything inside the safe should Molodkin’s demands not be met, and the WikiLeaks founder dies in jail.

“These destructive elements are connected to the life of Julian Assange through a dead man’s switch,” the 57-year-old artist explains. A close associate of Assange has the second timer, and the device is triggered if they fail to receive a daily confirmation that he is still alive. If no assurance is received, and the countdown reaches zero, the mechanism goes into self-destruct, turning the contents of the safe to white dust.

The work draws attention to Assange’s hearing at London’s High Court next week, which may well prove to be the final challenge to his extradition to the US, where he would face several charges, including one of espionage, carrying a maximum total sentence of 175 years. The charges relate to the publication of many thousands of leaked documents about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as a series of revealing diplomatic cables. Assange has been held at Belmarsh high security prison since 2019, jailed in a cell smaller than Molodkin’s 13x9ft safe, having previously taken refuge at the Ecuadorian embassy in London, where he held out for seven years.

One has to take Molodkin’s word that the project is no stunt. He will not name the individual artworks held ‘hostage’, just the names of the artists. But The New Yorker, well known for its forensic approach to fact checking, has gone some way to verifying that works to the value of around $40m have been donated.

“I don't want to speak about it as a provocation, because it is a serious artwork,” Molodkin says. He is sat at a dining table at his home in Cauterets in southwestern France, across the yard from the former foundry he has redeveloped into an experimental art space over the past decade.

The 32-tonne safe room filled with art © The Foundry Studio

Franco B and Petr Davydtchenko have made works there, as has Andres Serrano, making much of his Torture series on the premises. Molodkin’s own work has been censored, both at the Russian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2009, and in the US. His recent work, Putin Filled with the Blood of Ukrainians, is unlikely to endear him to authorities in his homeland.

Molodkin talks about Dead Man’s Switch as a kind of “symbolic portrait”, aligning his work with the what he calls the "Political Minimalism" of artists such as Santiago Sierra and fellow Russian Erik Bulatov, who has a permanent studio at The Foundry, and whose oversized artworks are dotted everywhere around the 4500 sq. m complex, including Forward, which was displayed outside Tate Modern in 2017 to mark the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution.

“I have produced this artwork, but it will have a life of its own. It is out of my hands now. Everything is in the hands of the administrations [that decide Assange’s future].” Molodkin claims that the fate of the works in the safe depends on the US government. He cites a Yahoo News investigation published in 2021 that alleges that the C.I.A. and the Trump administration discussed the possibility of kidnapping or assassinating Assange, and that it spied illegally on him while in the Ecuadorian embassy in London. The threat to Assange is real, Molodkin claims. But he and the artists and collectors he has collaborated with “believe that he will be free”, he says. “We believe that we have created a dialogue through a cultural platform, and that nothing will be destroyed. But, we are ready.”

Asked why he uses such threatening imagery, Molodkin replies that “it is not a provocation, it is just a language”. He continues: “We have war everywhere. There are hostages everywhere. Yet it is more taboo to destroy an artwork than to destroy human life. In this time of catastrophe, we have to find a language with which to communicate with power structures. And it has to be the same language [as they use].”

© The Foundry

Molodkin invited The Art Newspaper to come and see Dead Man’s Switch a few days before the safe door is locked and the digital timer triggers into action. It is installed within a grand but otherwise empty hallway in La Raillère, a former spa resort an hour’s drive away from The Foundry on the edge of Cauterets, close to the Spanish border. The only road into town corkscrews up to the 19th-century sanitorium, dramatically overshadowed by some of the highest peaks in the Pyrénées. This suitably Bond-like location had laid empty for nearly 30 years before Molodkin acquired it, and he has spent the past three years renovating it into a space for artists.

“Ever since the Russian avant-garde, it’s been a dream for artists to have a place, a platform, where they can stay together as a community and do anything that they want, to experiment, make accidents, where they have the right to make mistakes.” And while The Foundry is more focused on heavy production, La Raillère will invite artists that also use electronic media and sound. “The idea is that it will be a kind of alternative museum on the mountain, where people can live together with their work. It will look almost like you live inside Tate Modern.”