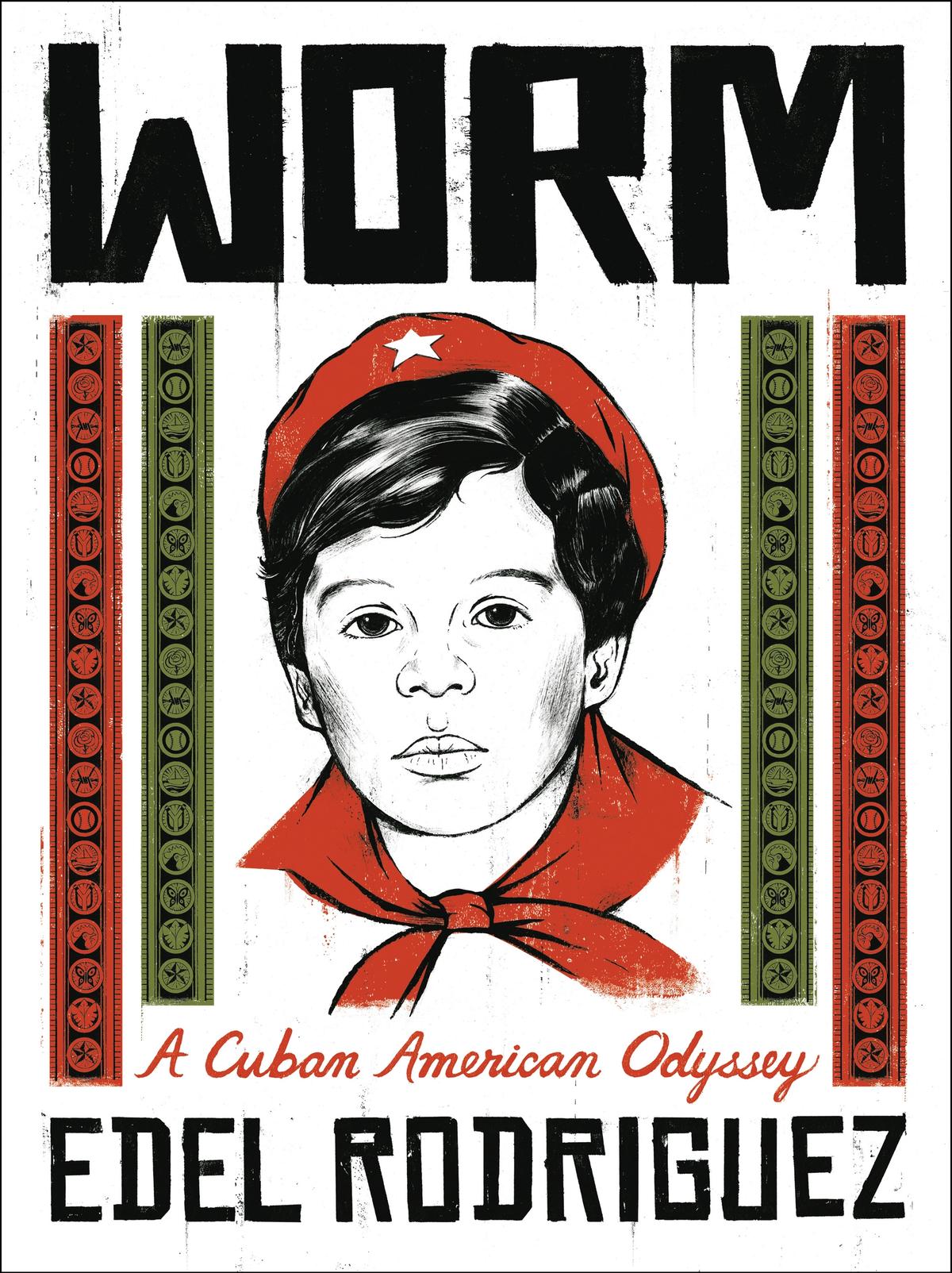

On the cover of the graphic memoir Worm: A Cuban American Odyssey, which follows the artist and illustrator Edel Rodriguez from 1970s Cuba to the US, the author draws himself as a boy wearing the red scarf of the José Martí Pioneer Organization and a beret with a star high on his head—the attribute of no less than Ernesto “Che” Guevara.

Che, in a 1960 photograph taken by Alberto Korda and reproduced infinitely ever since, was (and continues to be) the closest thing Cuba has to Andy Warhol’s Marilyn.

The earnest boy in Worm looks as innocent as a poster child for a religious pilgrimage. Portraits of the Cuban leader Fidel Castro and Guevara were enlarged to epic size, Pop art style, for mass rallies that thousands of those children attended.

Once past the cover art of Worm, we get a child’s vivid reality check, entering the purgatory of the involuntary Arte Povera of a crumbling post-revolution society behind the official portraits, following Rodriguez (born 1971) through the everyday austerity and scarcity of a village south of Havana. Drawn in a scratchy monochrome overlaid with baths of red—a backhanded homage to Warhol?—it was a grim existence beyond the scope of Castro pomp, but still under constant police surveillance.

Things got worse. Rodriguez and his family became pariahs when they applied for passports to leave Cuba, bullied by government thugs who screamed the word guzano, Spanish for worm—the official insult for citizens who wanted to flee.

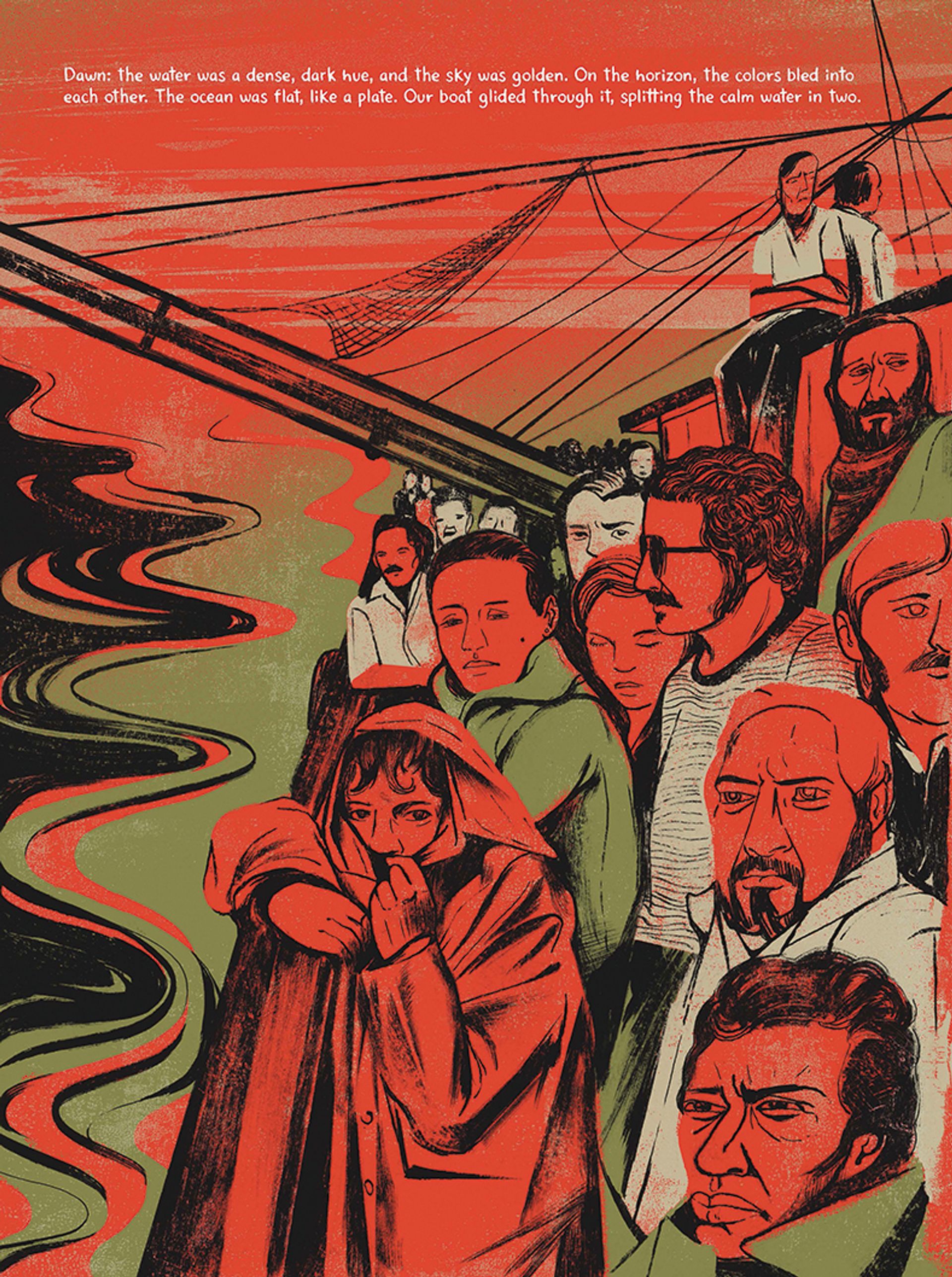

Eventually the family boarded a creaky ship (the Nature Boy) to Miami—along with prisoners, gay Cubans and other officially designated “scum” (escoria)—in the 1980 boatlift from the port of Mariel. Years later, Rodriguez’s talents as a draughtsman won him study grants and an eventual job at Time magazine. The broader public discovered this immigrant from drawings and magazine covers in 2016 depicting an empty-faced Donald Trump with an open mouth, yellow hair and orange skin, the decapitated Statue of Liberty’s bleeding head in one hand and a bloody knife in the other.

Rodriguez made his reputation with such incendiary images that blended a wit fuelled by René Magritte with the Pop grotesquery of the band Kiss (once his favourite), and a hint of the American Pop artist Tom Wesselmann. In Worm, he sustains a life story with those images in a minimal palette, set mostly in the impoverished Cuban countryside where his relatives risked prison for pilfering state-owned pigs to roast for family feasts.

Dawn Boat, depicting Edel Rodriguez and his family departing Cuba on a boat named Nature Boy © 2023 Edel Rodriguez

Exile and nostalgia have been the stuff of Cuban literature since soon after Castro seized power in 1959. The longing of ex-Castroites in exile who felt betrayed by the revolution is a genre in itself. Artists and intellectuals abroad soured on Cuba after the jailed poet Heberto Padilla confessed publicly in 1970 to being a “counter-revolutionary”. Reinaldo Arenas, a prolific poet whose memoir Before Night Falls scandalised the macho comandantes with tales of gay abandon, landed in prison, where “scum” were brutalised. Arenas fled to the US on a boat from Mariel (as Rodriguez did) after Castro emptied prisons in 1980. Infected with HIV, he killed himself in 1990. Arenas was played by Javier Bardem in the 2000 film adaptation of his memoir, directed by the painter Julian Schnabel.

In Worm there is no nostalgia. The revolution is all that its author knew. Rodriguez’s tales of life under that regime begin with a wide-angle view of guerrillas armed and bearded, standing victorious at the Presidential Palace in 1959—a two-page spread that seems inspired by history painting.

From rural life to film noir

Closer to home in the muddy village of El Gabriel, there is not much to eat, people share streets with animals and families rely on the black market for essentials, much of which we see in a palette that shifts from grey everyday rural life to the chiaroscuro of film noir once the family manoeuvres to leave. Given the tropical setting, Rodriguez does not show much sun except in scenes of the gruelling harvest of sugarcane, the same job most did before the revolution.

Memoirs of life under the Castro regime have set the bar high, but Rodriguez offers poignant moments of his own, like struggling to hide the blood of pigs butchered in secret. Under constant surveillance, suspected offenders suffered brutal and humiliating punishments, as in a scene where an investigator forces Rodriguez’s mother, herself once a lax local Communist party member, to disrobe in front of her son.

The book turns a corner back to Pop art when Rodriguez sees the threat of dictatorship in his adopted America. Donald Trump, running for president, called for a border wall to keep out Mexican “rapists”. Rodriguez, already “scum” in another country, seized on Trump the performer in images that he intended for his own website. His Trump figure, in a black suit and red tie, was constructed of modules—yellow hair, orange skin and a face that was empty, except for an open mouth. With those elements, and Rodriguez’s own memories of four-hour speeches by Castro to crowds of undernourished Cubans forced to listen, the angry authoritarianism feels familiar.

Rodriguez feared that depicting Trump as an executioner (of an ideal) would scare off publishers

Castro wasn’t the only model for Trump. The Statue of Liberty’s decapitator puts Trump in the stance of an Islamic State killer. Rodriguez feared that depicting Trump as an executioner (of an ideal) would scare off publishers—but Der Spiegel sought him out and put the image on its cover in February 2017. Other Der Spiegel covers by Rodriguez imagined a tidal wave in the form of Trump’s face engulfing Washington, DC, and a figure wearing a white hood and a red tie, with the title The Real Face of Donald Trump. (The angularity calls the New Yorker artist Saul Steinberg to mind.)

For Time magazine, Rodriguez drew Trump’s face melting down on the page or rising as a huge flame—mute, as magazine images are, yet always with his mouth open in anger.

“I don’t really look at pictures of him,” Rodriguez said in an interview for the Milanote website. “It’s all just symbols and graphics in my head. Part of the reason there are no visual cues is that I don’t want to draw his eyes and his nose. How could you just sit there and render his face? I just can’t do it. I won’t do it.” (Perhaps that’s why Rodriguez includes no portraits of Castro early in his memoir.)

Worm is Rodriguez’s first book, and it is an accomplished one. He pulls few punches, although this journey from Cuba to an America under threat from a thug feels unfinished, like a work in progress—and all the more ominous for it.

- Edel Rodriguez, Worm: A Cuban American Odyssey, Metropolitan/Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 304pp, $29.99/£20 (hb), published 7 November 2023

- David D’Arcy is a correspondent for The Art Newspaper in New York