Museo Jumex, a major engine in Mexico City’s transformation into a contemporary art hub, is celebrating its tenth anniversary with programming that includes the group exhibition Everything Gets Lighter, curated by Lisa Philips, the director of New York City’s New Museum, and the upcoming first survey of Damien Hirst’s work at a Mexican institution. Philips’s exhibition traces the three-decade collecting journey of the museum’s founder, Eugenio López Alonso.

The group show features works by 67 artists from the Colección Jumex such as Light and Space icons James Turrell, Mary Corse and Dan Flavin, painting giants Gerhard Richter and Robert Rauschenberg, and key Latin American figures like Ana Mendieta, Damián Ortega and Ernesto Neto. Its title is taken from a poem by John Giorno, whose rainbow-hued painting Everyone Gets Lighter (2015) is also represented in the show, and closes on 11 February—just as the 20th edition of the Zona Maco fair wraps up.

Installation view Colección Jumex: Everything Gets Lighter. Museo Jumex, 2023-24. Photo: Ramiro Chaves.

López credits a 1995 visit to the Saatchi Gallery’s Boundary Road space with sparking his desire to open a similar institution in his native country.“If people were coming to an old factory on the outskirts of London, they could come to mine in Ecatepec,” he says. “A motivation to collect international artists” was part of his vision from day one; he started connecting with dealers and hired Patricia Martin as his first curator.

When a 15,000 sq. ft space, designed by Gerardo García, opened on the premises of López’s family business Grupo Jumex in the early 2000s, some members of the public were baffled by its distance from Mexico City and the founder’s determination to blend international contemporary art with local names. “We thought nobody would come but they did,” he says. With a programme of two shows per year, the industrial space became a unique art hub and destination.

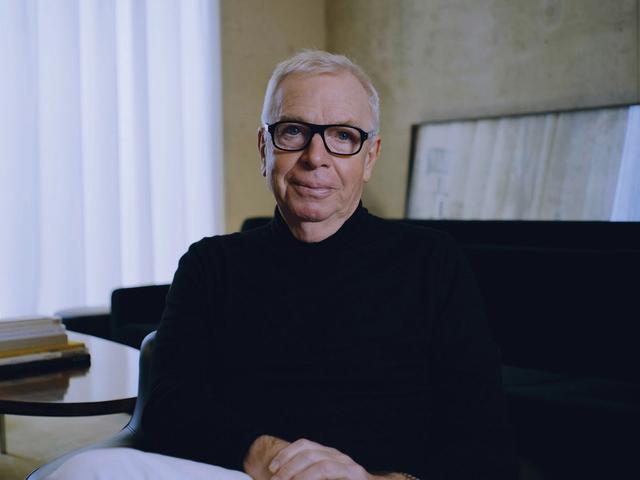

López had caught the patronage bug and had bigger ambitions. “I told my father I wanted a space in downtown Mexico City and I wanted to hire an international architect because there were no buildings by non-Mexicans around at the time,” he says. He formed an instant bond with the British architect David Chipperfield during their first meeting, and Chipperfield was soon commissioned to develop the Fundación Jumex Arte Contemporáneo’s next chapter. The founder’s only request was to make sure natural light entered each floor of the building. “When I learned he won the Pritzker Prize, I was shocked because for first time the winner of such a prize would have a building in Latin America,” he says.

Jeff Koons, Seated Ballerina, 2017. Museo Jumex, 2019 Photo: Moritz Bernoully

The 17,000 sq. ft building opened in autumn 2013 as part of the Plaza Carso, where another Mexican businessman, Carlos Slim, has his Fernando Romero-designed Museo Soumaya. Located in Mexico City’s buzzy Nuevo Polanco district, Museo Jumex has since hosted blockbuster shows. Its Andy Warhol exhibition, Dark Star,attracted around 310,000 attendees in 2017; the pairing of Jeff Koons and Marcel Duchamp in the two-artist show Naked Appearance saw around 400,000 guests during its 2019 run. The public response has often been a mix of surprise and wonder, López says. “People came up to me to express their surprise to see a Warhol in Mexico City.” Shows organised by Museo Jumex have also had an impact beyond Mexico City, travelling to the Museum of Modern Art and Dia Art Foundation in New York, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, MoMA, Dia Art Foundation, LACMA, Walker Art Center, Museum of Art of São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand and the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid.

Crowd-pleasing installations on the plaza in front of the museum have included Koons’s gargantuan ballerina sculpture in 2017 and Rirkrit Tiravanija’s participatory ping pong piece, Untitled [Tomorrow is the Question] in 2012. “Every time we put art outside, it has to be either spectacular in size or something that the public can play with,” he says.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled [Tomorrow is the Question], 2012. Museo Jumex, 2015

Everything Gets Lighter looks back on the institution’s first decade and reflects López’s ongoing collecting. His quarter-century friendship with Philips, via his role as a member of the board of trustees at the New Museum, made her his first choice to curate the anniversary show. “She is someone who makes everything so easy,” he says. “She told me she would only do this for me.” He adds that he handed Philips the keys to his collection with his “eyes closed” because “I knew she would always surprise me”.

The pairing of patron and curator yielded an intriguing journey through the collection and around the building spanning new works to Dan Flavin’s fluorescent light sculpture, Untitled (Monument for V Tatlin) (1964), the oldest work in the show. Artists who have had major solo shows at Museo Jumex over its first decade, like Pedro Reyes, Urs Fischer and Abraham Cruzvillegas, are represented, as are Tacita Dean, Tala Madani, Pia Camil, Roni Horn, Lina Bo Bardi and others. The eye-catching public work on the plaza is Olafur Eliasson’s aquatic sculpture, Waterfall (1998).

Installation view Colección Jumex: Everything Gets Lighter. Museo Jumex, 2023-24. Photo: Ramiro Chaves.

López is not surprised by the growing numbers of local galleries and international dealers opening outposts in Mexico City and around the country. “I always waited to see this moment,” he says, adding that the city’s flourishing art market reflects a rapidly expanding collector base. “There was me and a few others [when he started collecting], but thanks to the local galleries and artists, there are so many collectors in Mexico now.”

A key factor in Museo Jumex’s success is López’s knack for showmanship and crowd-pleasing. In reference to the forthcoming Hirst show To Live Forever (For A While) (23 March-25 August), organised by former Tate curator Ann Galagher, he says: “I told Damien whatever he wants to show, he has to bring the shark!” Around 60 works by the Turner Prize-winning artist, created between 1986 and 2019, will be featured, including famous series like his medicine cabinets sculptures and the butterfly paintings—and, of course, a certain fish suspended in formaldehyde.